History of Photography in China, 1839–ca. 1911: Selected Annotated Bibliography

Created in conjunction with the exhibition Brush & Shutter: Early Photography in China at the J. Paul Getty Museum, February 8–May 1, 2011, and the accompanying catalog of the same name

Created 2011

Compilers: Shi Chen, Julia Grimes, Tiffany Lee, Jia Tan, Linlin Wang

Editors: Jeffrey W. Cody and Frances Terpak

Created 2011

Compilers: Shi Chen, Julia Grimes, Tiffany Lee, Jia Tan, Linlin Wang

Editors: Jeffrey W. Cody and Frances Terpak

Note to the Reader

This bibliography represents the state of research into the field of Chinese photography through March 2010. It was created in conjunction with the exhibition Brush & Shutter: Early Photography in China at the J. Paul Getty Museum, February 8–May 1, 2011, and the accompanying catalog of the same name.

In this bibliography, pinyin will usually be used to romanize Chinese characters. For example, Guangzhou is the name for the city formerly known as Canton. However, in the cases of Macau and Hong Kong, we have retained the earlier accepted romanizations.

All Chinese names have been alphabetized according to their pinyin spellings and follow the Chinese custom of placing the surname (xing) first, unless the individual lives in the West and places the surname last.

This bibliography represents the state of research into the field of Chinese photography through March 2010. It was created in conjunction with the exhibition Brush & Shutter: Early Photography in China at the J. Paul Getty Museum, February 8–May 1, 2011, and the accompanying catalog of the same name.

In this bibliography, pinyin will usually be used to romanize Chinese characters. For example, Guangzhou is the name for the city formerly known as Canton. However, in the cases of Macau and Hong Kong, we have retained the earlier accepted romanizations.

All Chinese names have been alphabetized according to their pinyin spellings and follow the Chinese custom of placing the surname (xing) first, unless the individual lives in the West and places the surname last.

Translations of Chinese-language titles have been provided where appropriate. Those translations given by the authors or publishers of a work are prefaced by an "=" sign, while parentheses indicate a translation by the compilers of the bibliography.

A Chinese-language version of this bibliography may be found in the translation of the catalog published by Hong Kong University Press.

A Chinese-language version of this bibliography may be found in the translation of the catalog published by Hong Kong University Press.

Introduction

|

|

Photography in China had been an overlooked area of studies, in both China and abroad, until the last decade of the twentieth century. However, in the late 1990s, possibly due to the popularity of the Lao zhaopian (Old photographs) series, there was a proliferation of Chinese publications related to China and photography, particularly in a series format. Since the late 1970s, as the legitimacy of the socialist ideology merged with the reality of a market economy, China has reformed and globalized its market. Thus, while the state has urged society to look forward rather than backward, there has also been a strong nostalgic desire by many Chinese to understand, consume, and visualize China's past with greater clarity. The late-blooming publishing craze related to nineteenth and early twentieth-century photography should be understood as one of these efforts to grasp, memorize, and re-evaluate history, particularly in the context of rapid modernization.

There are several distinguishing features of these heavily illustrated, popular publications. Often, photographs are used broadly as proofs of historical events, but no specific year or source information is given. Frequently, the same pictures have been reproduced in several publications. Although many of the Chinese publications provide a wealth of graphic material, a substantial number of them neglect to provide comprehensive documentation, such as original sources, exact dates, photographers' names, or locations. Published for a popular audience, these series serve as a means to better understand the social aspects associated with significant historical changes in China during the late Qing dynasty (ca. 1840–1911).

|

|

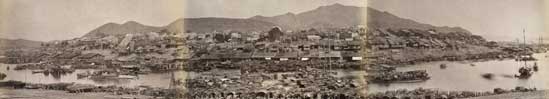

Scholars interested in Chinese visual culture in the early twenty-first century have increasingly turned their attention to analyzing early photographs as primary documents in the study of Chinese history. Consequently, photographs have served as visual materials that help to illuminate larger social and cultural histories of certain coastal cities, notably Shanghai and Hong Kong. The increasing interest in visual culture can also be measured by the number of exhibitions dedicated to historical photography, both in China and abroad. Early Chinese photographs have also become desirable and profitable objects to collect, both for public institutions and private collectors. As can be seen in the references below, since the mid-1990s, an increasing number of exhibition catalogs, or books featuring particular collections, have been published.

The time period for this bibliography—1839 to ca.1911—was chosen because it coincides roughly with the blossoming of the photography medium after 1839, the burgeoning power of Western commercial interests in China after the Opium Wars of 1839–42 and 1856–60, the rise of the treaty port system in association with those interests, and finally the decline of the Qing dynasty in the latter half of the nineteenth century, culminating in its demise in 1911. During this period of dramatic change in China and the West, a growing curiosity about China resulted in the establishment of photographic studios, along with images taken by foreigners living or traveling in China. Early photographs of China reached an international audience in the form of photo albums, cartes-de-visite, stereographs, postcards, and press photographs. Photography by indigenous makers also became popular during this period, which later led to a booming industry of photographic studios and press agencies in several Chinese cities and to the publication in Europe of seminal works that featured Chinese photographs or prints made from photographs.

However, during the Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) and the Civil War (1945–49) in China, both the Chinese and Japanese colonial governments censored photography. After 1949, China's Communist Party, which controlled the publishing industry as a part of the state-controlled media, mostly produced political propaganda to motivate the masses to participate energetically in the creation of a new socialist culture. From 1949 until the late 1970s not much attention was directed to the study of China's recent cultural past due to the ideology of the Cold War and China's shunning of the West. It was not until the 1990s that books with a focus on photography were published both in China and abroad.

Mindful of the difference between perceiving photography as a subject of study and as a technique to produce historical records, this bibliography is divided into three sections: the history of photography, the interpretation of history through photographs, and published collections. Because the field of the history of photography in China is expanding so rapidly, the bibliography is by no means comprehensive. Instead, it seeks to reflect the state of the field through March 2010. Because it is intended to serve an English readership who might not be familiar with the burgeoning scholarship in Chinese devoted to photography, more attention will be focused here on publications in Chinese. Due to their significance or popularity, some entries are annotated in more detail than others. In a few cases, it has not been possible to consult the original Chinese texts, and therefore there are no annotations. Each section contains references to books, articles, and significant websites. Citations, which are listed alphabetically, were located by searching through online databases (e.g., ProQuest, JSTOR, Bibliography of the History of Art, FirstSearch, and World Cat). Chinese citations were located either by cross-referencing existing articles and publications or by consulting databases such as the Academic Journals Full-Text Database and the China Doctoral Dissertations Full Text Database.