Our Lord in the Attic: A Case Study

Museum's history

- 'De Amstelkring'

- The first museum's exhibits

- Development of the museum until 1952

- Development of the museum 1952-1991

- Development of the museum since 1991

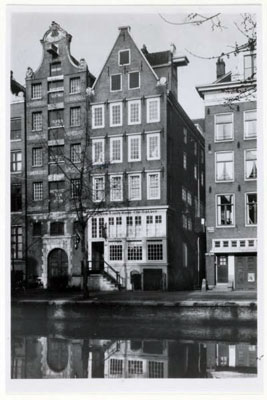

Museum Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder is one of the oldest museums in the country. It was established in 1888, the year in which an association of Catholic citizens of Amsterdam – who called themselves “De Amstelkring” – saved the building from demolition and opened it to the public.

Museum Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder is one of the oldest museums in the country. It was established in 1888, the year in which an association of Catholic citizens of Amsterdam – who called themselves “De Amstelkring” – saved the building from demolition and opened it to the public.

The building was reportedly in bad condition because of neglect: walls were cracked in several locations, the roof had major problems and the beams were at risk of severe sagging. Because of a lack of funding, only the most crucial repairs were undertaken between June 1887 and April 1888. The kitchen, which is nowadays referred to as the 19th century kitchen, was installed, using old tiles from a different house.

The official opening of ‘Museum Amstelkring’ was on Tuesday 24 April 1888 and it was opened to the public on the 28th, which makes it the second oldest in the city, after the Rijksmuseum. In the early days visitors could only visit the museum after making an appointment.

Cross section showing areas open to the public in 1888 - areas in gray were not open to the public, but were in use as offices or were sublet.

'De Amstelkring'

The Catholic foundation ‘De Amstelkring’ was established in 1883 and its main task was to carry out research into the history of the Catholic Church in Amsterdam. Its board members were all from well-established, rich Catholic families. At first, the foundation collected mainly books and prints and drawings, but soon after also other valuable objects. This fast growing collection was housed in a small room at the vicarage of the ‘Begijnhof’ (beguinage) in Amsterdam.

In 1884 the foundation discussed ways to prevent demolition of the church in the attic at Heintje Hoekssteeg. Indeed, the matter was urgent, as the building of the new St. Nicholas Church was commissioned that year. Plans existed to sell the old attic church to pay towards this new structure. Over the next couple of years, the foundation discussed buying the old church to establish a museum for their own collection. Amstelkring eventually bought the building on 31 May 1887 for 6,000 Dutch Florins.

In 1884 the foundation discussed ways to prevent demolition of the church in the attic at Heintje Hoekssteeg. Indeed, the matter was urgent, as the building of the new St. Nicholas Church was commissioned that year. Plans existed to sell the old attic church to pay towards this new structure. Over the next couple of years, the foundation discussed buying the old church to establish a museum for their own collection. Amstelkring eventually bought the building on 31 May 1887 for 6,000 Dutch Florins.

The museum is still owned by this foundation, whose goals have remained unchanged: to conserve the building and keep it accessible to the public.

The first museum's exhibits

|

|

From the time of the purchase the museum exhibitions were planned. Heated discussions eventually led to removal of the church furniture and the transformation of the fixed benches for dignitaries (placed in 1737) into showcases. The church was filled with all kinds of objects, smaller ones in showcases and larger objects on open display. Still existing old photographs give a good impression of the set-up. They show the showcases in the main area of the church. The walls were completely covered with all kinds of objects.

This photos on the right show that the church was originally lit with what looks like bauxite gas lamps - these were replaced with enclosed gas or oil lamps by 1890. The lamps from that period have been electrified and are still in use today. Several objects are recognizable and today still form an important part of the collection, for example the statue of St. Paul (right hand side, near the stairs).

Church in 1932.

Leeuwenberg room, facing the Heintje Hoekssteeg (after the restoration of 1954-1960).

Development of the museum until 1952

The following describes the further development of the museum and, consequently, the related work to the building. The two are described together, as building work is often related to the museum’s position in time (e.g. interpretation issues, management, available resources, fashion, etc.).

In 1918, the exhibitions were changed and the showcases in the church were dismantled, recreating the situation from before 1887. The re-opening was on 23 June 1919.

In 1918, the exhibitions were changed and the showcases in the church were dismantled, recreating the situation from before 1887. The re-opening was on 23 June 1919.

However, the foundation became almost inactive; debts were accumulated, and in 1938 major plans for reorganization and restoration were presented to counteract this downward spiral. Objects that had no connection with the mission of the museum were to be sold, two exhibitions per year should attract more visitors and the museum was to actively recruit donors. Between 1938 and 1939, the building was restored and painted, electricity and the first form of central heating installed. The interiors were painted and the old balustrades, which were stored on the attic and loft, were reinstated in the church and on the galleries. It is recorded in 1939 that worn parts of the wooden floor in the church and the stairs in the front of the house were replaced with wood from another old house. The exhibitions were renewed and temporary exhibitions were installed.

Although the museum was now much better organized, financial problems persisted. To resolve this, plans progressed in 1950 to make it a monastery for nuns, whereby large parts of the collection were to be auctioned. Those interested could visit the sael and the church by appointment. However, these plans were prevented and on 1 June 1951 the museum reopened after a thorough clean and provisional reinstating of the exhibitions. For the first time, the museum was given professional staff to take care of the building and its collection. This was only achieved by accepting subsidies from the federal government.

Development of the museum 1952-1991

From 1952, Jaap Leeuwenberg, scientific researcher at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, became board member of the museum. He was very influential and wealthy. He personally funded the acquisition of several important paintings. He was also responsible for the decoration and display of the period rooms. From 1954-1960, the building was restored with the help of the ‘Monumentenzorg’ (bureau for the care of monuments) of the city of Amsterdam. This restoration was extensive and integrated the two houses at the back with the main building. The second house at the rear was reconstructed creating the present layout. The original stone floor on the first floor (the Jaap Leeuwenberg room) was uncovered and reinstated. The kitchen on the ground floor was restored to a 17th century style.

From 1952, Jaap Leeuwenberg, scientific researcher at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, became board member of the museum. He was very influential and wealthy. He personally funded the acquisition of several important paintings. He was also responsible for the decoration and display of the period rooms. From 1954-1960, the building was restored with the help of the ‘Monumentenzorg’ (bureau for the care of monuments) of the city of Amsterdam. This restoration was extensive and integrated the two houses at the back with the main building. The second house at the rear was reconstructed creating the present layout. The original stone floor on the first floor (the Jaap Leeuwenberg room) was uncovered and reinstated. The kitchen on the ground floor was restored to a 17th century style.

In the middle of the 1960’s, the condition of the building and its collection was considered stable, and the board focused on securing a ‘cordon sanitair’ around the museum, by buying several ruinous buildings surrounding the museum and replacing them with new ones. Increased violence in the Red Light District, which is where the museum is located, was considered to be harmful to the museum. By renting out the properties, the exploitation of the museum could be secured. Leeuwenberg covered the costs of this campaign and he donated the buildings to the museum. In the current situation, the museum still owns and sublets houses in the vicinity of the museum. The building directly adjacent to the museum (on the left) is in private hands and houses a Thai restaurant.

Development of the museum since 1991

In the period 1999-2001, the canal room and sael were renovated and their 17th century interior reinstated. In 2003, the entrance and antechamber were renovated and decorated in 19th century style.

At present, the presentation of the collections (house and movable collection) is of a mixed nature. There are parts in the museum which reflect the history of the house as well as several rooms which are used as an exhibition room. There are also rooms which show a combination of the two. Only recently the museum is trying to bring back the spirit of the place, a house that was lived and worked in for hundreds of years. In the near future this means that the exhibition rooms will be changed back to their original function (as living quarters from different periods and a church). In rooms which now have a plural function, the objects will be taken out which have no relation with the original function of the room.