Our Lord in the Attic: A Case Study

Building construction

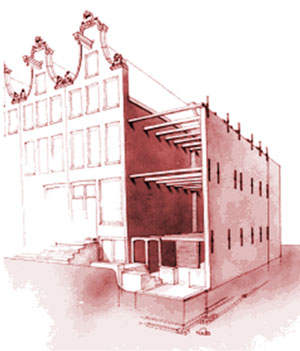

Cross section of the main house.

Cross section of the main house and the house at the back.

The outside wall facing the alley, showing the iron cross ties.

View into the small inner court at the back of the building.

Building construction

|

|

Since Amsterdam is located on a bog, houses are built on a typical foundation of wooden poles. Long wooden beams, basically entire trees of 13 to 20 meters long, were drilled into the soil to reach the firmer sediment layer of sand. The poles were placed in pairs, next to each other, with a distance of 80 cm between the pairs. The poles have to be kept under water to maintain an anaerobic environment and avoid rotting. The water levels in the city have therefore always been carefully maintained. Heavy foundation beams were nailed on top of the poles, which were first cut at the same level. These formed the basis for the house.

On top of these beams, several layers of stone were built with loam (in Dutch ‘leem’). 5 to 6 layers of bricks were laid on top with a tough mortar of sand, and lime, with the purpose of blocking rising damp.

Then the walls were built in brick (Amsterdam bricks were 18/19 x 9 x 4.3 cm), using lime mortar. Walls were either 1 or 1.5 bricks thick (i.e. 18/19 - 27/28 cm). The walls were built up to the first level, where pine beams were placed to create the floors. What is exceptional in this house is that the beams were placed vertically on their shorter side, rather then laying flat on their wider side. This is unusual for the time period. It was known that beams placed this way were stronger, but beams were usually placed flat, in order to have a minimal loss of height. The exposed wood inside was later painted with linseed oil based paint. The beam heads were covered with tar to avoid wood rot. At the beam heads, iron cross ties were placed to counteract the natural outward bending of the brick walls and to create a strong joint between beams and walls. When reaching the intended height of the outside walls, the wooden roof construction was built. Last but not least, the roof tiles were put in place. Lead lined gutters and downspouts are used to deal with precipitation.

Until 1570/1580, oak wood was the type of wood used in Amsterdam for building houses, but by the time this house was constructed, oak was becoming scares and expensive. Softwood (pine) from the Netherlands, but also imported, was then gradually introduced. In the 17th century, oak wood was still considered superior and was therefore used in parts that are visible, in this house e.g. in the windows of the sael. Construction elements were built using pine. Sometimes pine beams were used, which were covered with oak – this was done in the cassette ceiling in the sael.

The brick walls were not plastered on the outside. At the back of the houses on the Heintje Hoekssteeg is a small inner court – its outside walls are plastered. On the inside the walls were as normal in those days plastered with lime plaster. The original plaster survived in the sael.

Listen to an architect explaining some of the features of this house:

First form of central heating in the church (located in the fixed benches for dignitaries) .

Original stairs covered with new steps.

Canal room after restoration

Museum during the 2005 roof restoration.

Work to the building

Following is a brief list of known maintenance, repair and restoration work to the building in chronological order:

- The soft yellow/green color scheme for the exposed internal woodwork, currently still in use, was first introduced in the first part of the 19th century.

- In 1894, the roof was repaired.

- In 1904, windows with relatively easy access (windows in the alley, on the roof and facing the court yard) were fitted with iron bars as burglary prevention.

- Between 1938 and 1939, the building was restored and painted. Electricity and the first form of central heating was installed .

- From 1954-1960, the building was restored with the help of the ‘Monumentenzorg’ (the bureau for the care of monuments) of the city of Amsterdam. The foundations at the corner of Heintje Hoekssteeg and Oudezijds Voorburgwal and the walls of the former inner court were repaired up until approximately 5 meters above street level. The original division of the windows was reinstated and the roof was fixed. The restoration integrated the two houses at the back with the main building. The second house at the back was reconstructed creating the present layout. The original stone floor on the first floor (the Leeuwenberg room) was uncovered and reinstated. The additional wooden floor and balustrades were newly installed. The kitchen on the ground floor was restored to a 17th century style. Central heating was also installed throughout the rest of the house in this period. Apart from the canal room, sael and reception area (reconstructed in 2001-2003), the painting of most of the interiors dates back to this restoration.

- The last time the outside of the building was painted was in the late sixties and seventies.

- In 1970 the steps of several of the stair cases were covered by new oak planks.

- In 1974, the toilets for the visitors were placed in the basement of the first house on the Heintje Hoekssteeg. These are still in use today.

- Between 1999 and 2001, the canal room and sael were restored.

- Around 2001, damage to the top of the tension rod, connecting the galleries on the SW side of the church (closest to the altar) to the roof construction was repaired (it was broken and had to be welded together). In the 1970’s it was already noticed that this tension rod had completely corroded at the top part, where it connects to the wooden beam of the roof construction. The situation was assessed in 1988 but it is unclear if any action was undertaken at that time. Just before repairing this damage, temporary measures were put in place to allow access to this gallery to ordinary museum visitation, but to close the galleries to large crowds. After this repair, that restriction was lifted.

- In 2003 both the entrance and antechamber were renovated.

- In 2005 the roof was restored; old tiles in good condition were re-used as much as possible, new tiles were used to complement. Lead was replaced where necessary and gutters and downspouts were replaced. Gable cross ties were conserved and rotten wooden combles (in Dutch ‘spanten’) were treated or replaced.

Damage to one of the beam heads

Condensation on the windows and consequent damage to the window sills

Condition of the building

Canal houses in Amsterdam suffer from sagging (listen to the architect), because the poles have a certain amount of spring. Immediately after construction, the poles compress slightly, caused by traffic (historically these were carriages) and people walking, but also due to natural compression of the soil, which clings to the poles. The house on the Oudezijds Voorburgwal is built on the corner of an alley, the Heintje Hoekssteeg. Corner houses are prone to sag away from the corner towards the adjacent alley, in the direction of the long side of the building. On the outside one can often observe the walls of these corner houses curving out into the adjacent alley. This also happened to this building, but the deformation was treated during the restoration in the 1950’s.

Beams

There has been an issue (first mentioned in the 1970’s) with the rotting of beam heads in the north wall of the building at the church’s third level floor (the 6th level of the building). The wall at this level is exposed to the weather (there is no connecting building at this level). No other rotting has been found in other walls except one with an obvious rain infiltration problem. The beam heads were impregnated with an epoxy resin, the walls were stuccoed and painted. The reason for this rotting might have been twofold, but which of the following reasons is the most likely cause of the damage remains uncertain:

- The old wall may have developed cracks that were infiltrated by outside rain, resulting in the rotting beam heads. Rain generally wets north-facing walls in the Netherlands, and these walls tend to remain wet for long periods afterwards, since the relative humidity in the air is usual high.

- Another explanation could be that rotting was caused by in situ condensation of the humidified air inside the building.

The windows

The windows in the building are single pane. In winter, there is often condensation on the inside of the windows, resulting in rapid decay of the window sills.

The windows in the building are single pane. In winter, there is often condensation on the inside of the windows, resulting in rapid decay of the window sills.

Sheets of lexane have been installed on the inside of the northeast and southeast facing windows in order to reduce UV levels and also as a protective measure against burglary and to avoid damage by broken glass in case a window is smashed in.