Beyond China

In the West, centuries before the invention of photography, perceptions about China were largely formed through export goods. Commercial ties between the Mediterranean world and East Asia brought tea, silk, ceramics, metalwork, and curios to European markets.

By the 1700s, as a result of increased commercial and religious activities that accompanied European imperialism in Asia, a pervasive taste for Chinese objects and stylistic adornments had developed.

![The Taking of Canton [Guangzhou] / C. Bommier The Taking of Canton [Guangzhou] / C. Bommier](images/bommier_1.jpg)

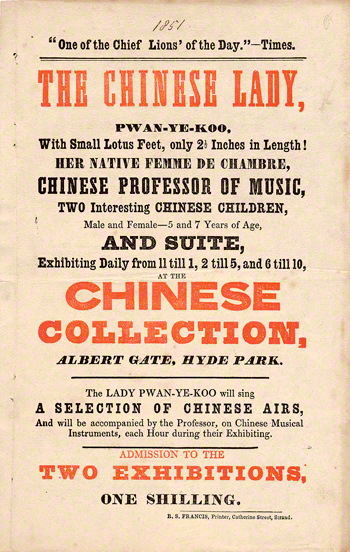

Missionary activities, particularly those initiated by the Jesuits in the late-1500s, resulted in a flow of information about China that was ultimately published, often with illustrations. Whether based on fact or fantasy, these early works piqued Western curiosity that intensified due to increased trade and Western intervention. In the 1800s Nathan Dunn's unusual array of Chinese art and artifacts was widely displayed in Philadelphia and London. As noted in the handbill for his 1851 display in Hyde Park Corner, Dunn's collection of "objects exclusively Chinese" surpassed "in extent and grandeur any similar display in the known world." Dunn's exhibition also showcased a "singing Chinese lady," as illustrated in the colored handbill.

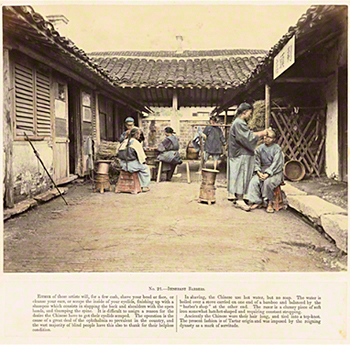

Brush & Shutter displays the work of Western photographers such as William Saunders, who modeled his images of street trades on earlier Chinese export gouaches, and the work of Chinese photographers who grafted the new technology of photography onto traditional Chinese aesthetic conventions. The early activities of these Chinese photographers, unrecognized to date, suggest the need for a new understanding of the history of photography in China that will emerge more fully as other private and public collections, particularly in China, are studied.