Rediscovering Ancient Mexico

After the conquest, the Spanish Crown prohibited non-Spanish subjects from traveling to colonial Latin America, a restriction that vanished with Mexican independence in 1821. European and American explorers and artists began to make frequent expeditions to Mexico, bringing with them new scientific and aesthetic ways of looking at ancient Mexican cultures and objects.

They used new forms of reproduction, such as lithography and photography, that made images more accessible. The reports and lavishly illustrated volumes that record their findings were aimed at both scholarly and popular audiences. The images the visitors created have both aesthetic and documentary value, as many of the places and objects they picture no longer exist or are now significantly changed. Above all, the images allow their viewers to travel across space and time, as though looking through an obsidian mirror to the worlds of the Aztecs, Maya, and other peoples of Pre-Columbian Mexico.

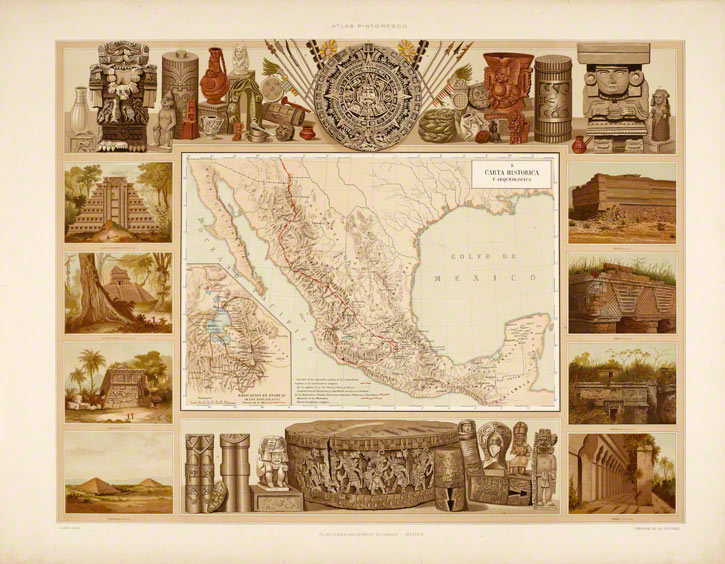

Mapping Mexico's Archaeological Sites

This map charts the major archaeological sites of Mexico. It is bordered at top and bottom by an assemblage of significant Pre-Columbian artifacts, such as the colossal statue of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue, the Aztec Calendar Stone, and the Stone of Tizoc; along its sides are scenes of archaeological sites, including Palenque, Uxmal, Chichén Itzá, Mitla, and Xochicalco.

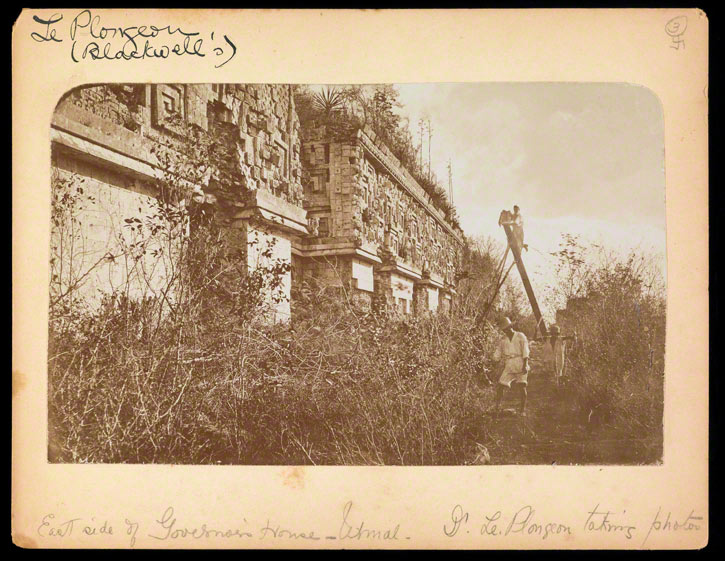

Photographing Mexico's Ancient Ruins

Both Alice and Augustus Le Plongeon were accomplished photographers. Alice was trained in the London studio of her father, Henry Dixon, while Augustus purportedly learned photography from Henry Fox Talbot, the English inventor of photography.

Here, Alice has recorded Augustus photographing the east facade of the Governor's Palace in Uxmal, a process that took several days. (See his panorama of the palace here.) His jaunty pose belies the laborious and precarious nature of the task.