|

|

|

Crossing of the Granicus (detail), Gérard Audran after Charles Le Brun, 1672

|

|

From the early 1660s until the middle of the 1680s, Charles Le Brun (1619–90) had unprecedented control of the visual and decorative arts in France. A prodigious artist and designer, he was King Louis XIV's principal painter, leader of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, and director of the huge royal manufactory's workshops of hundreds of artists and craftsmen.

The works in this exhibition reproduce Le Brun's designs for paintings and tapestries in the Grand Manner, the genre in which a heroic protagonist engages in a morally significant action—a battle to be won, a victory to be celebrated, or a vice to be avoided. Le Brun oversaw the production of these unusually large engravings and etchings, some of which are almost two meters wide and composed of multiple printing plates. By disseminating these subjects in printed form, Le Brun presented to collectors and artists his mastery of the most complex type of art. The quality and size of these prints, in turn, allowed Le Brun to demonstrate his authority over the fine arts in France.

|

|

|

|

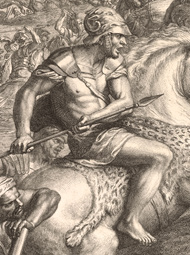

Crossing of the Granicus, Gérard Audran after Charles Le Brun, 1672

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the 1670s, the French royal press published a suite of five magnificent prints assembled from 15 copperplates. They reproduce the large paintings Charles Le Brun and his assistants made for the king's collections (the paintings are now in Paris and Versailles). These prints served to disseminate the king's collections throughout Europe and met the Crown's demand that artists in royal service glorify the king—here, Louis XIV is presented as the new Alexander the Great, conqueror of the ancient world. The prints also demonstrate Le Brun's role as a teacher, as they contain lessons on every aspect of the Grand Manner, from the expressions of each figure to the structure of the compositions.

This image depicts the moment when Alexander the Great's forces crossed into Asia in 334 B.C. and engaged the Persian army on the banks of the river Granicus (Kocabas) near the site of ancient Troy. Alexander, in the center of the composition, finds himself surrounded by Persians wearing winged helmets and turbans. The fate of his enemies is sealed by the ax of the nearby Clitus the Black, an officer in Alexander's elite cavalry. The conceit of the image points to Alexander's triumph as evidence of heroic princely virtue. Thus, as the print's motto states, "Virtue surmounts every obstacle."

|

|

|

|

|

Triumph of the New Testament over the Old Testament (detail), Gérard Audran after Charles Le Brun, 1681

|

|

|

|

This print is one of five that, when trimmed and assembled together (see the assembled image), represent Le Brun's fresco for the chapel cupola at the château of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the king's powerful overseer of the treasury, judiciary, and the arts. Painted in 1674, the fresco was destroyed in the early 19th century.

Surrounded by Old and New Testament symbols, God the Father witnesses the baptism of his son (not shown here) and pronounces, "This is my beloved Son." The fresco's subject complemented a sculptural group for the high altar, the marble Baptism of Christ designed by Le Brun and executed by Jean-Baptiste Tuby. The large, irregularly shaped copperplates from which these sheets were pulled undoubtedly posed a challenge to the printmaker and to the printer. For the whole image to be legible and pleasing, the width and depth of the incised lines had to be consistent and each part uniformly printed.

|

|

|

|

Battle at the Milvian Bridge, Gérard Audran after Charles Le Brun, 1666

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1666, acting as his own publisher, Le Brun released his first two prints, episodes from the life of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great. Relatively few painters had the means to publish their own designs; fewer still had the wherewithal to produce huge images printed from multiple copperplates.

The Battle at the Milvian Bridge, after an unfinished painting by Le Brun, was meant to prove he had surpassed the famous version designed by Raphael for the Vatican in the early 16th century.

In A.D. 312, Constantine established himself as the sole ruler of the western Roman Empire when he defeated the so-called breakaway emperor, Maxentius. In this image, Constantine charges across a bridge just outside of Rome toward Maxentius, who has fallen victim to his own trap as he grasps his horse and tumbles backward toward the Tiber River. Le Brun's message is clear: Louis XIV is the modern-day Constantine enforcing peace. With peace established, all the arts flourish, namely those celebrating the king's glory.

|

|

|

|

|

Fall of the Rebel Angels, Alexis I Loir after Charles Le Brun, ca. 1685–86

|

|

|

|

|

|

In this last large print published by Le Brun, the armed archangel Michael banishes a slithering mass of rebellious angels from the heavens. This design is part of a larger composition that Le Brun hoped to execute as a painting for a church in Paris, and the picture of contorted bodies relies heavily upon the work of the Flemish baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens.

Le Brun tried to secure the painting commission by dedicating the print to the new superintendent overseeing royal patronage, François-Michel Le Tellier, the marquis de Louvois, whose patron saint was the archangel Michael. The subject of the image refers to Louvois's role as the minister of war and his persecution of French Protestants, who were considered potential rebels against the state and the church. Despite the flattering dedication, Louvois refused to commission the painting, signaling Le Brun's diminished power over the arts in France.

|

|