|

The splendor of the late medieval court of the dukes of Burgundy evokes the legendary Camelot. Its magnificence was expressed in lavish banquets, pageants, and tournaments, as well as luxury goods such as tapestries, paintings, metalwork, and particularly illuminated manuscripts.

This exhibition traces the tradition of Netherlandish manuscript painting from the 12th century to its extraordinary flowering in the 15th and 16th centuries. By the mid-1400s the Burgundians held sway over much of the Netherlands, including the prosperous Flemish towns of Ghent and Bruges (in present-day Belgium) and the Dutch city of Utrecht—all important centers of manuscript production. At this time Netherlandish books, especially from Ghent and Bruges, dominated the European market. They were created for an international clientele of princes, dukes, cardinals, bishops, and wealthy burghers.

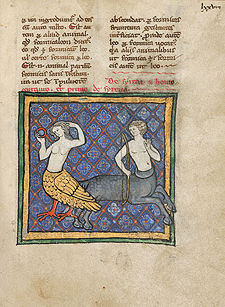

The image above is from a bestiary, a collection of moralizing descriptions of real and mythical beasts, and one of the most popular books of the 1200s in northern Europe. The bird-women Sirens lured sailors to their deaths with song, and represented worldly temptation. Centaurs, whose human appearance above the waist belied their beastly nature below, represented hypocrisy.

|

|

|

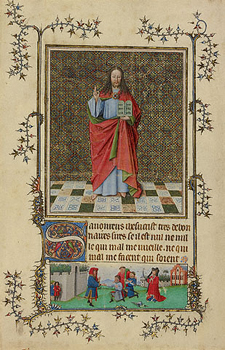

The head of Christ depicted here is based on a lost oil painting by Jan van Eyck (Flemish, died 1441). Although this illumination was executed in tempera on parchment, the artist—probably trained in Van Eyck's workshop—captured the naturalism of the original.

The different shades of red in Christ's robe were applied in thin, semitransparent layers like the glazes used by oil painters. Christ's hair displays exceptional detail, subtle color, and soft light. The exquisitely tooled checkerboard patterning, or diapering, of the background further demonstrates the technical sophistication of manuscript illumination in Bruges by the mid-1400s.

Audio: Curator Thomas Kren tells the history behind this book. Audio: Curator Thomas Kren tells the history behind this book.

On view during second installation:

November 9, 2010–February 6, 2011

|

|

|

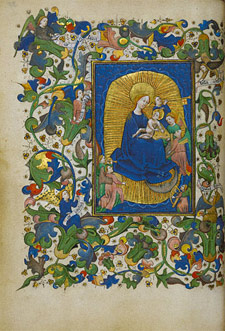

At left, attended by music-making angels, the Virgin Mary sits humbly on the ground, a motif that reflects her modesty and purity. Yet the page itself is a riot of color and light: the border is thick with large, swirling flowers, while a golden aureole of dense rays surrounds Mary.

The border decoration and central image are further linked by a shared palette of blue, green, and gold.

On view during first installation:

August 24–November 7, 2010

|

|

|

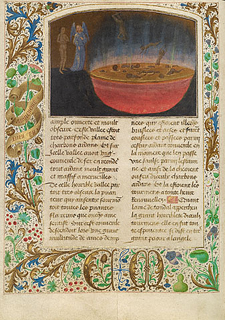

The Visions of the Knight Tondal tells the story of a wealthy and errant Irish knight whose soul is led on a journey through hell and paradise with an angel as his guide. Here they arrive at a deep valley filled with burning coals, where murderers are punished. The sinners' souls fall onto a hot iron lid placed over the chasm—jets of green and blue gas escape from the glowing surface.

This manuscript is the only surviving illuminated copy of the text. It was commissioned by Margaret of York, duchess of Burgundy and wife of Charles the Bold from 1468 to 1477; their initials appear in the border of each painted page.

Audio: Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times film critic, explores this image. Audio: Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times film critic, explores this image.

On view during second installation:

November 9, 2010–February 6, 2011

|

|

|

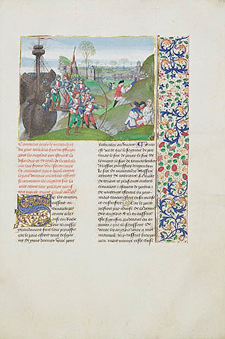

Jean Froissart's Chronicles recounts the history of England and France from 1322 to 1410, including their extended conflict known as the Hundred Years' War. The manuscript is a narrative of political events: diplomacy, strategic marriages, court intrigues, battles, and assassinations. This image shows the English forces laying siege to the city of La Rochelle, on the coast of Brittany, in 1388.

Louis Gruuthuse, a counselor to the duke Charles the Bold and a great bibliophile, inspired Edward IV of England (ruled 1461–1483) to start his own library after the king had spent 1470–71 exiled in Bruges. Following his return to England, Edward acquired a substantial group of illuminated manuscripts from the Burgundian Netherlands. Among them were several volumes of the Chronicles, probably including this copy.

Audio: Curator Elizabeth Morrison explores this eyewitness account of the Hundred Years' War. Audio: Curator Elizabeth Morrison explores this eyewitness account of the Hundred Years' War.

On view during first installation:

August 24–November 7, 2010

|

|

|

The illuminators of Ghent and Bruges (in present-day Belgium) gave their works an unparalleled richness by painting nearly every square inch of a page. They sometimes accomplished this by surrounding the central image with related narrative scenes.

This manuscript pairs episodes from Christ's childhood (such as the Nativity on the left page) with those from his Passion (right)—the events leading up to his persecution and death. The page on the right features Christ's first appearance before the Roman high priest Caiaphas. In its left border, Christ meets his mother, an event preceding his encounter with the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, who sends him to King Herod. At upper right, Herod asks to see a miracle. His request unfulfilled, he mocks Christ, has him clad in a white robe, and returns him to Pilate.

Audio: Curator Thomas Kren walks us through this opening. Audio: Curator Thomas Kren walks us through this opening.

On view during second installation: November 9, 2010–February 6, 2011

|

|

|

A nocturnal setting heightens the drama of the betrayal of Jesus Christ by his disciple Judas and his arrest by Roman soldiers. Torches and Christ's halo illuminate the violent scene against the evening sky. Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, elector and archbishop of Mainz and an ambitious patron of the arts, commissioned this book and its 42 images. They relate the story of the life of Christ, especially his Passion and death, in painstaking detail.

The famed artist Simon Bening drew his patronage from the ruling class of Europe, including Germany, Spain, Portugal, England, and the Netherlands. The cardinal had this manuscript copied from an illustrated book printed in Augsburg in 1521, preferring the luxury of a handwritten and painted version to a mass-produced one.

On view during first installation:

August 24–November 7, 2010

|

|

|

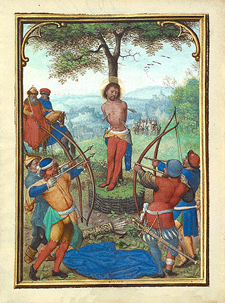

Simon Bening, the finest Flemish illuminator of the 1500s, became famous for his landscape settings. Within very small formats, Bening represented vast spaces. In this image of the persecution of Saint Sebastian, the central event is set on a hilltop that overlooks a rugged terrain and sprawling town, both bathed in an evocative haze.

The death of Sebastian was ordered by the emperor Diocletian (ruled 284–305), who appears on horseback at left. Sebastian recovered from his flesh wounds, only to endure a second torture by flagellation.

On view during second installation:

November 9, 2010–February 6, 2011

|

|

Audio: Curator Thomas Kren tells the history behind this book.

Audio: Curator Thomas Kren tells the history behind this book.