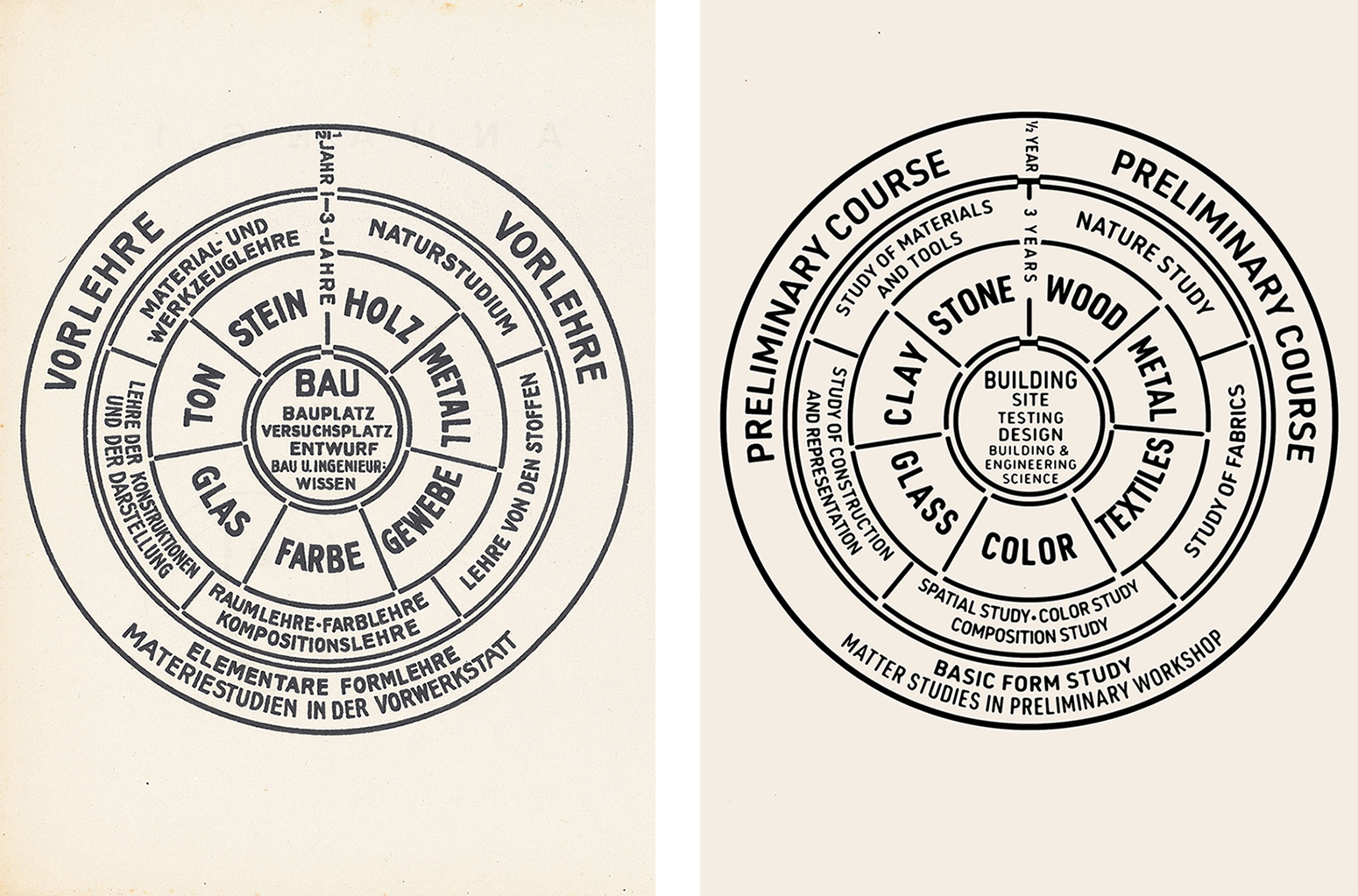

Principles and Curriculum

If Walter Gropius’s 1919 manifesto had proposed a radical vision for a new institution that would erode distinctions between artists and artisans, it was the school’s unprecedented pedagogy, represented in the circular curricular diagram (see fig. 14), that enacted this revolutionary ideal. At the Bauhaus, all students in their first semester enrolled in the compulsory, half-year Preliminary Course (Vorlehre or Vorkurs), represented by the outermost ring of the diagram. This course investigated what Bauhaus masters considered to be the fundamentals of any artistic endeavor, whether applied or fine.

Supervised at first by Johannes Itten, then jointly by László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers, and finally by Albers on his own, the course explored theories of color and form, principles of composition, studies of materiality, exercises in life drawing, and visual analysis. More specialized courses in theory led by Paul Klee, Vassily Kandinsky, and others supplemented the Preliminary Course. The various exercises students performed in these courses represented an effort to promote a holistic education.

The concept of the workshop was key for Gropius: in his manifesto he writes, “The school is the servant of the workshop.”

After the successful completion of the Preliminary Course, students enrolled in specialized workshops devoted to specific crafts such as ceramics, weaving, carpentry, printing, metal, or stage design. The concept of the workshop was key for Gropius: in his manifesto he writes, “The school is the servant of the workshop.”1

Workshop-based education was certainly no novelty in early 20th-century Germany, but in line with Gropius’s postwar romantic vision, the medieval guild served as the model for organizing these workshops. Students worked as apprentices, dedicating years of practice to specific crafts, and learned by designing and executing products following the instruction of masters, both artisans and artists. The workshops represented a form of practical education in which students had the opportunity to apply the principles learned in the Preliminary Course to the hands-on process of design.

After completing one of these specialized workshops, only select students were to be admitted to the study of building. As “the ultimate goal of all creative activity,” building was the locus where objects produced in the various workshops (pottery, tapestries, stained glass, lamps, and the like) were to be brought together.2 Building figured prominently at the center of the Bauhaus curricular diagram. This ambition however was not fully realized until the final years of the Bauhaus; the school offered no formal courses in architecture until 1927, before which students could only gain experience by apprenticing in the private architectural office of Gropius and Adolf Meyer.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.The divergent trajectories students might follow at the Bauhaus were represented together in the curricular diagram. The singularity of the circle suggests the holistic nature of a Bauhaus education, in which individual students representing diverse disciplinary backgrounds were to come together in pursuit of a shared mission to reform art, design, and society.