Life Drawing

Understand the nude as … the highest nature, the finest articulation and organization, as an edifice of flesh, muscles, bones.1

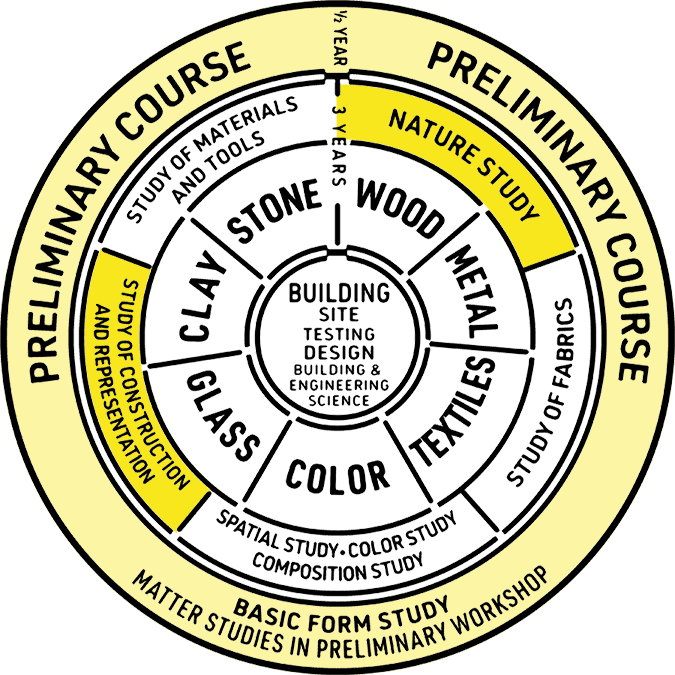

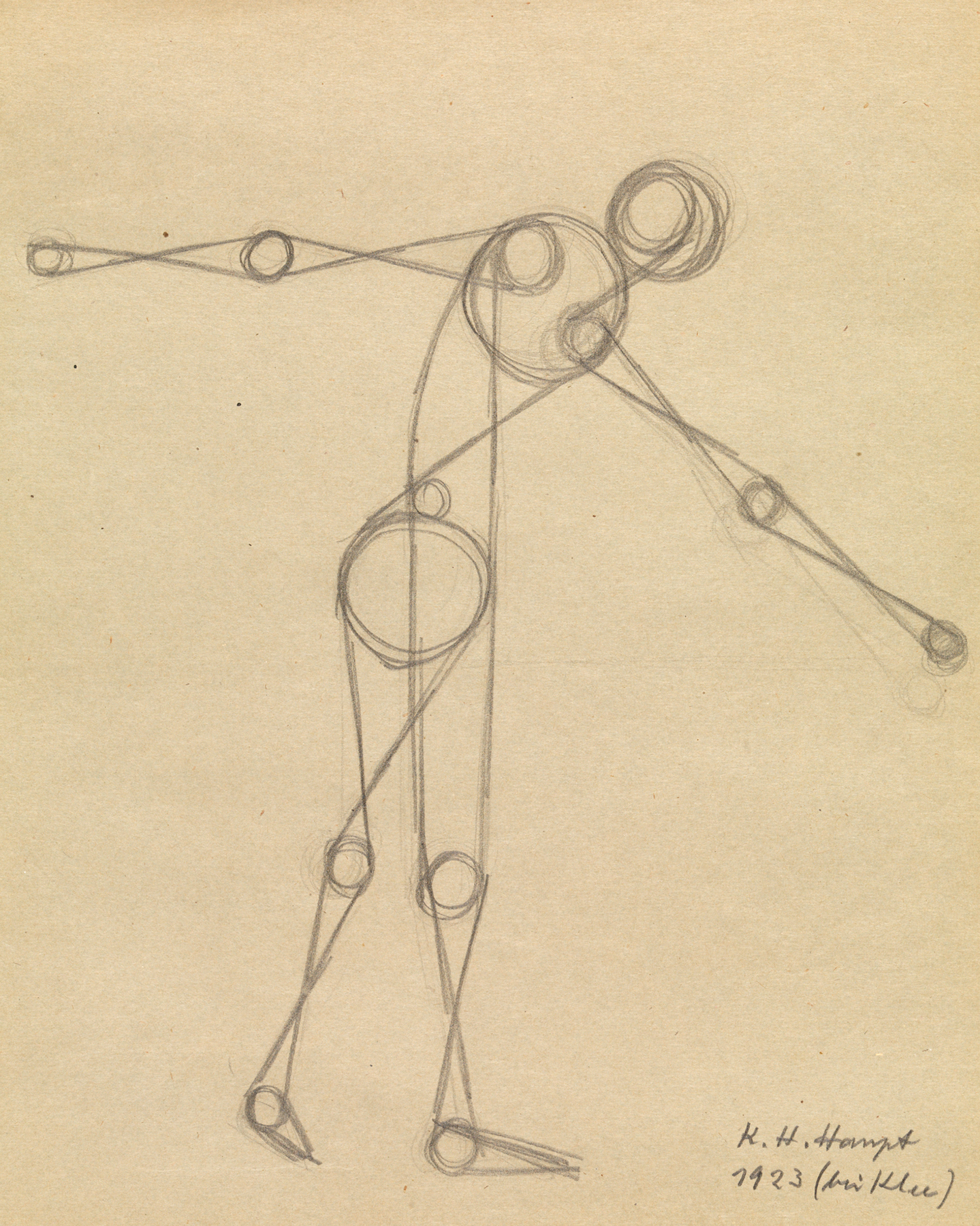

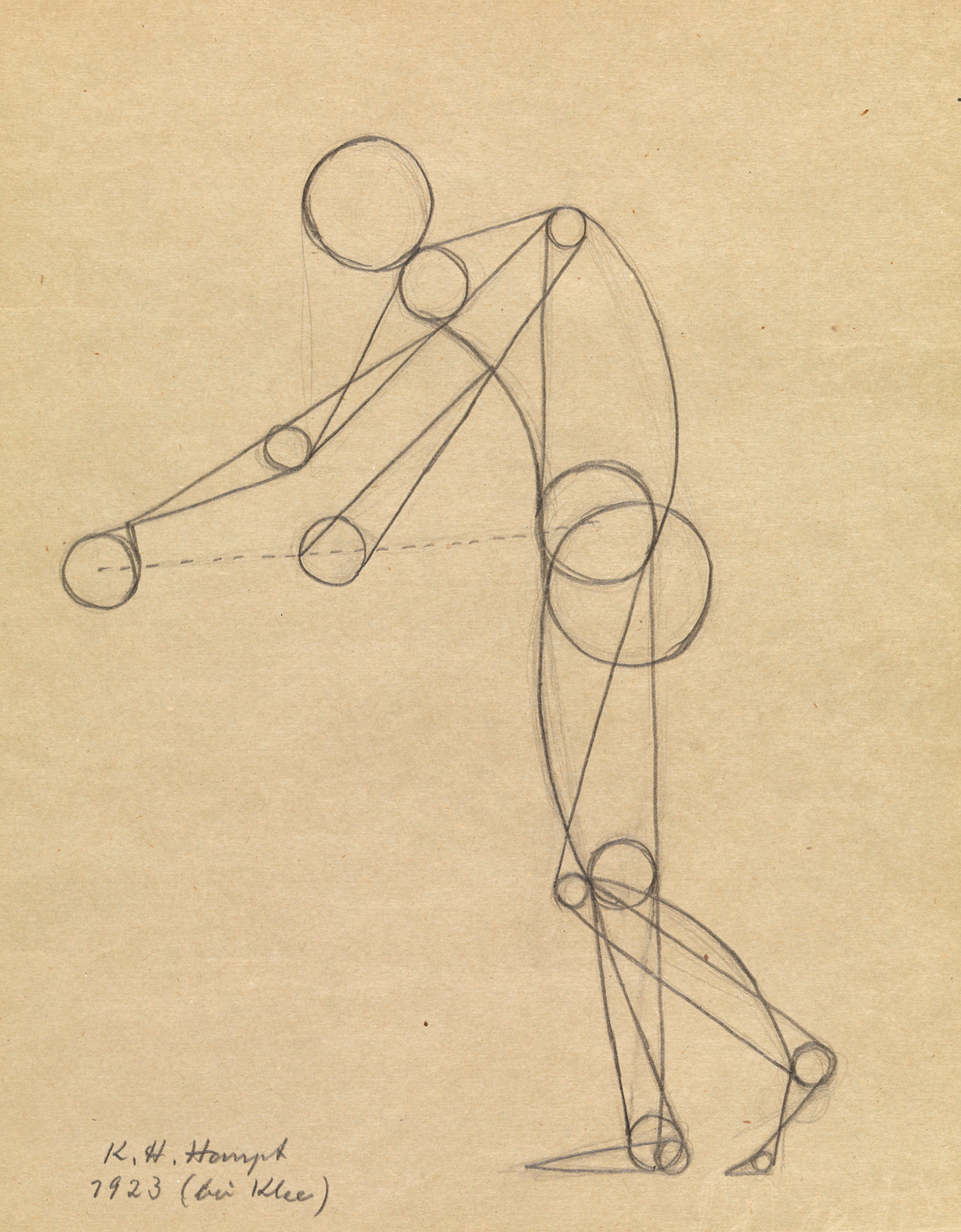

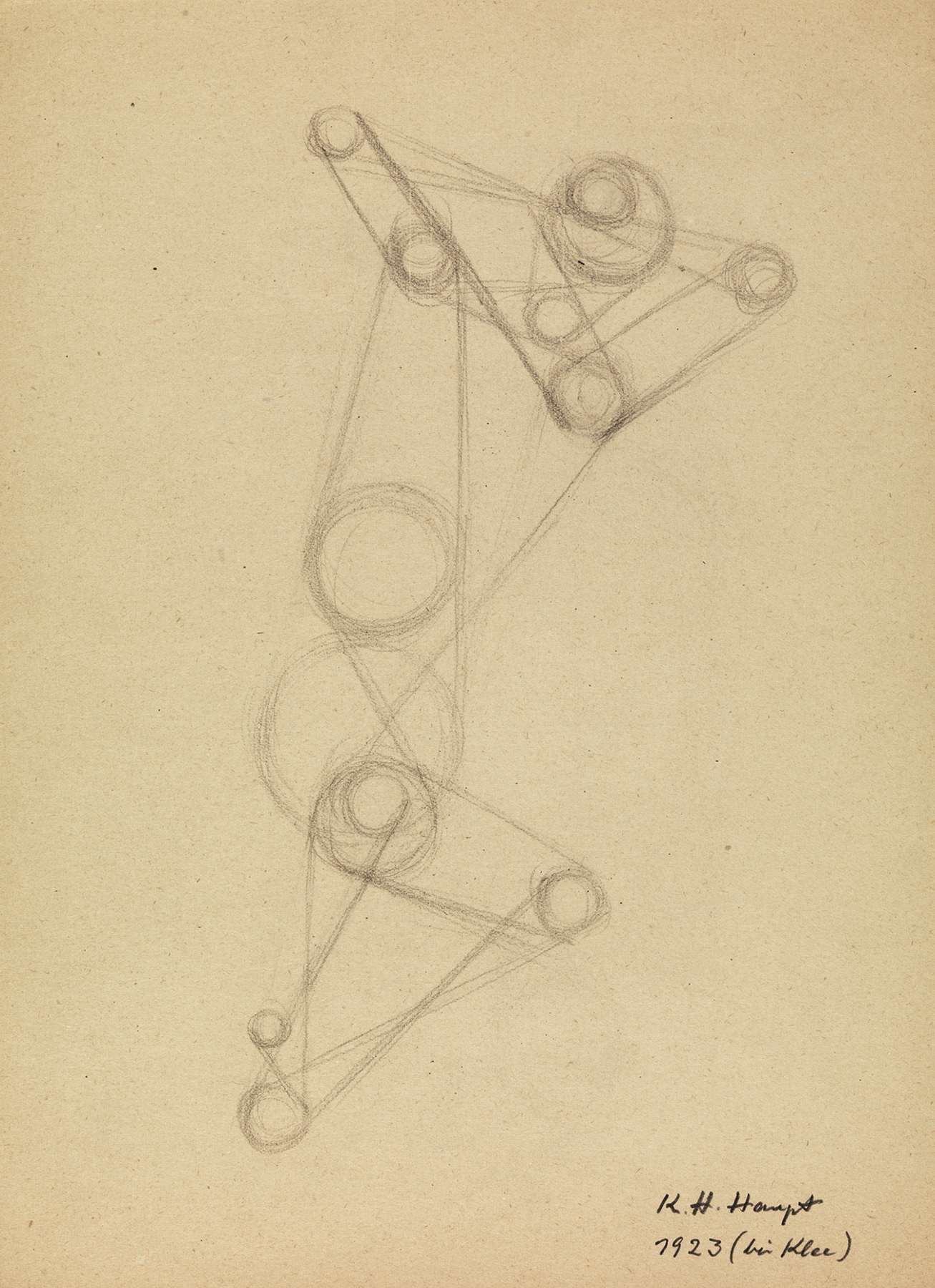

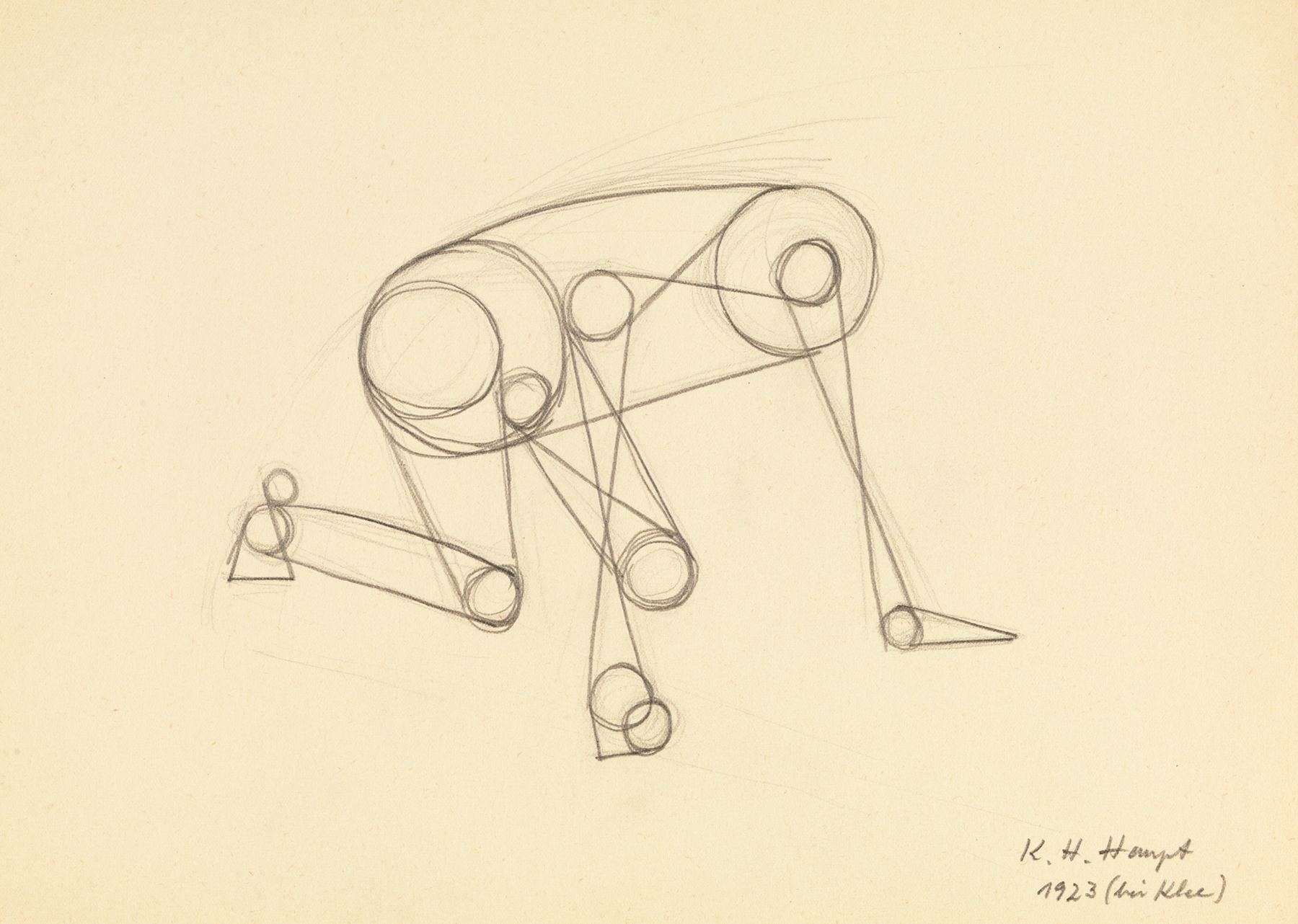

The first teaching assignment Oskar Schlemmer received when he joined the Bauhaus in Weimar was to lead the Life Drawing class, which focused on representation of the nude. Far from a return to the academic tradition, the stance he took, following Gropius’s request, was to look at the dynamic structure of the body and to capture the abstraction of its movements. Schlemmer understood the human body as the expression of “cosmic being,” a concept that led him to integrate his course The Human Being with classes on the nude and figure drawing. The latter were schematic representations of the body as lines and planes according to standard measurements and proportions. These followed both Leonardo da Vinci’s 15th-century attempts to bring to light physiognomics and anatomy, as well as drawings of bodily proportions included in Albrecht Dürer’s book Instructions on Measurement (1525).

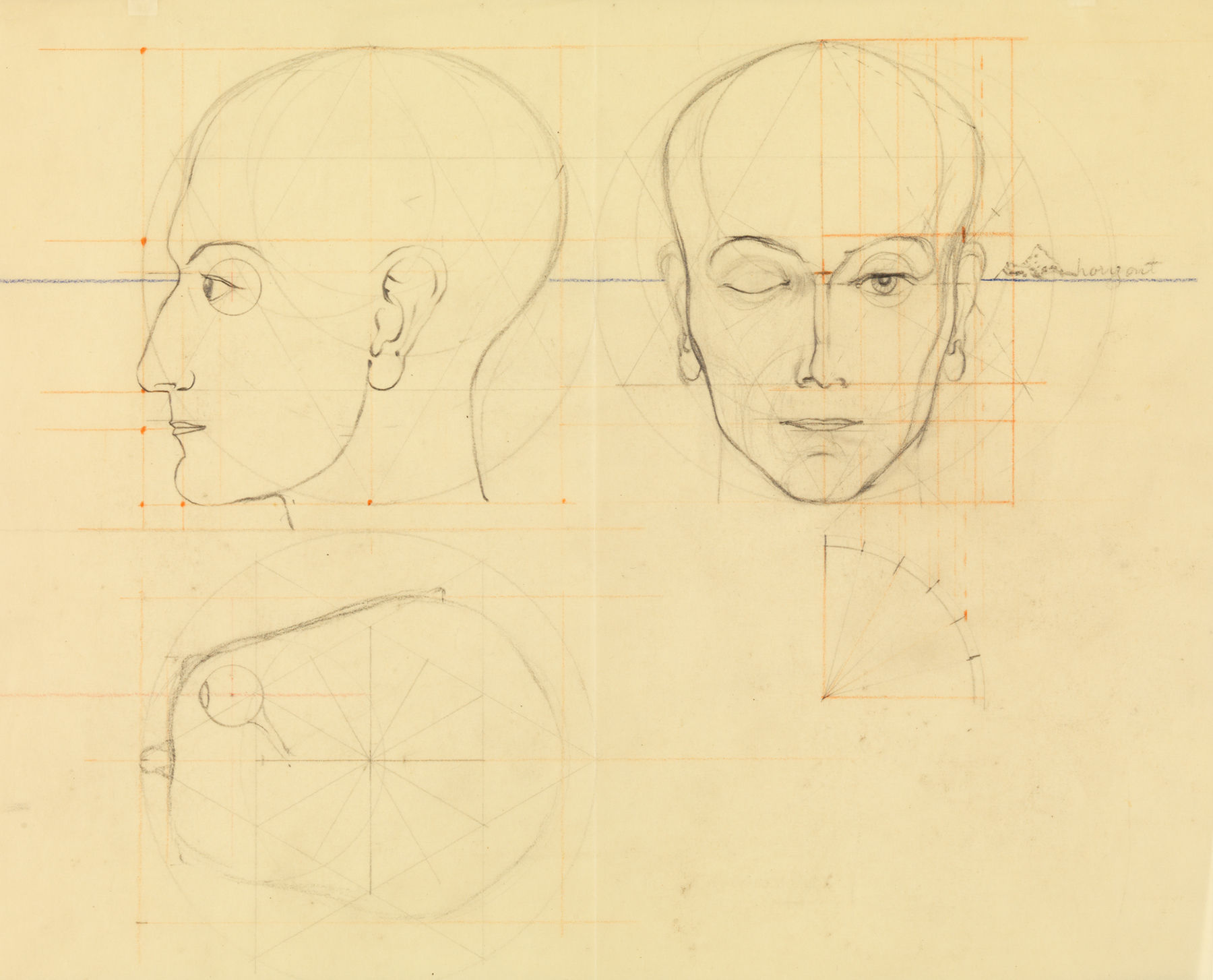

Schlemmer sought to impart to his students an appreciation for the figural representation of the body that accounted for its relation to space. This spatial relationship comprised abstract systems of lines and planes emphasizing the solidity and plasticity of the body. Both these geometric exercises and live-model drawing sessions were compulsory for all students. Because a variety of bodies was essential to the success of these classes, students frequently posed as models in a studio transformed into a kind of stage through the use of props, spotlights, and even gramophone music.

Schlemmer sought a figural representation of the body that accounted for its relation to space.

In an early entry in his Diary (1915), Schlemmer revealed his basic interest in reducing the natural forms of the body to geometric figures: the body could be broken down into “the square of the ribcage, the circle of the belly, the cylinder of the neck, the cylinders of the arms and lower thighs, the circles of the elbow joints, elbows, knees, shoulders, knuckles, the circles of the head, the eyes, the triangle of the nose.”2 Students were encouraged to capture the essential features of the body, from its joints and movements to its muscular structure and down to its skeleton. Natural sciences therefore emerged as a relevant component of the Life Drawing syllabus. Attention was given to physiology, and, more problematically, to phrenology and the comparison of skulls.

An understanding of the human figure conceived in three-dimensional space was the ultimate goal of these exercises. Through his own painting and physical arrangements, Schlemmer exposed the students to architectonic motifs, increasingly reimagining the spatialized figure as both concrete experience and pure fantasy.

Notes

- Oskar Schlemmer, diary entry dated February 1925, in Oskar Schlemmer, Man: Teaching Notes from the Bauhaus, ed., Heimo Kuckling (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1971), 41. ↩

- Oskar Schlemmer, diary entry dated October 1915, in The Letters and Diaries of Oskar Schlemmer, ed. Tut Schlemmer (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1972), 32. ↩