Much of the following information is based on the chapter on documentary photography in Beaumont Newhall's The History of Photography, published in 1982 (see Bibliography).

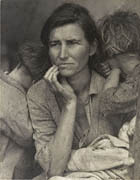

Any photograph that faithfully records a moment or situation might be considered "documentary." The term "social-documentary," however, is reserved for those pictures that both record human life and conditions and attempt to present the subject with compassion, often with an aim to reveal social injustice and advocate reform. It is this characteristic that distinguishes social-documentary pictures from studio portraits, landscapes, art photographs, or news images.

Dorothea Lange's approach to photography was instinctively documentary. She described it this way: "First—hands off! Whatever I photograph,I do not molest or tamper with or arrange. Second—a sense of place. Whatever I photograph, I try to picture as part of its surroundings, as having roots. Third—a sense of time. Whatever I photograph, I try to show as having its position in the past or the present."

Early Documentary Photographers

Lange was not the first photographer to create straightforward, informative, and sympathetic depictions of the world that are intended to generate reform. The social-documentary impulse in photography may have first found expression in the work of Jacob Riis, an American photographer who published a series of images in 1890 that suggested a link between poverty and behavior. Following in Riis's footsteps, Lewis Hine took pictures of immigrants in the eastern United States in the early 1900s. Deeply concerned about the conditions of their lives, he photographed them as they arrived at Ellis Island and also in New York's sweatshops and tenements. Hine's shocking images of children working in factories were widely published and led to the passage of laws regulating child labor

The Photographic Essay

The "photographic essay" has often been employed by documentary photographers. Rather than create a single, stand-alone image of a subject, documentary photographers (especially those who make social-documentary pictures) often assemble a series of pictures to illustrate a topic. Doing so allows them to reveal more of the subject and to make the presentation more compelling and nuanced.

|

||

As Lange noted: "I find that it has become instinctive, habitual, necessary, to group photographs. I used to think in terms of single photographs, the bull's-eye technique. No more." Examples of Lange's many documentary photo-essays include the series she composed on the daily life of a public defender and another she produced for Life magazine on three Mormon villages.

Like many social-documentary photographers, Lange felt that words could support and enhance her pictures. Her first major endeavor reflecting this interest was An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, published in 1939. The book was a collaborative effort between Lange and her husband, economist Paul Taylor. Lange paired her work with excerpts from recorded conversations with her subjects, and Taylor provided an accompanying historical text.

The "Truthfulness" of Documentary Photography

The task of creating a documentary photograph is not simple, despite the seemingly straightforward nature of the resulting image. Documentary photographers must constantly ask themselves to what extent they are truly recording the scene before them or whether they are somehow manipulating it to create an impression that was predetermined in their own mind. Another difficulty arises when documentary photographers are so eager to record human suffering that they forget to depict their subjects in any other light. Lange herself did not hesitate to aim her camera at people in misery, but said, "I had to get my camera to register the things that were more important than how poor they were—their pride, their strength, their spirit."