|

People of the Twentieth Century, the collective portrait of German society made by German photographer August Sander, has fascinated viewers from its earliest presentation in a 1927 exhibition and the controversial publication of a selection of 60 images in the book Face of the Time published two years later. Despite Sander's dedication over five decades to the idea and compilation of this portrait atlas of the German people, the project remained unfinished. Nonetheless, his photographs remain compelling, in part because he chose to categorize his subjects by profession or social class. The images are thus representations of types, as he intended them to be, rather than portraits of individuals.

Selected from the Getty Museum's substantial holdings of Sander's work, this exhibition of 130 photographs explores the promise of his vision in a condensed view of his ambitious project. Sander believed that society was organized into a hierarchy of occupations. One section of his project is dedicated to the skilled tradesman, including master craftsmen, industrialists, technicians, and inventors. Subjects associated with intellectual or "white-collar" labor were usually photographed indoors in three-quarter-length poses, while master craftsmen were portrayed in their working environment with the tools of their trades. Portrayed as he emerges from the dark basement of a building, the coal carrier in the image above belongs to the lower ranks of labor and is symbolically associated with the bowels of German society.

|

|

|

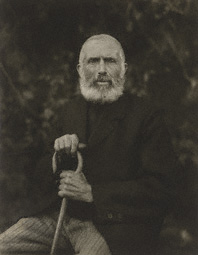

The first section of People of the Twentieth Century is dedicated to the farmer. It begins with a Stammappe, or portfolio of archetypes. Usually three-quarter-length portraits, the photographs depict old farming men, women, and couples seated in their homes or against a natural backdrop. Each is captioned to suggest the fundamental role played by the individual in a balanced society. Sander referred to this farmer as the "earthbound man." Other archetypes include the "philosopher," the "fighter or revolutionary," and the "sage." All had female counterparts, while couples were labeled as "propriety and harmony."

The section also includes portfolios of the young farmer and his family, his work and life, farming types, the small-town dweller, and sport. Lasting several seconds, the exposures required by Sander's large-plate camera encouraged his subjects to arrange themselves and carefully pose.

|

|

|

The businessman and parliamentarian Johannes Scheerer, seen in this image, was one of many individuals at the fringes of the political spectrum. Here he shoulders his umbrella like a shotgun, measuring up the viewer with an owlish, suspicious glance. Behind this formidable facade lurks a character more akin to a provincial schoolmaster than a legislator.

The image belongs to one of the larger sections in Sander's project, classes and professions, which sprawls through portfolios that depict the student, scholar, official, doctor and pharmacist, judge and attorney, soldier, aristocrat, clergyman, teacher and educator, businessman, and politician. In many of these portraits, a neutral background emphasizes the details of the sitters' facial features and clothing. Sander's later addition of National Socialists to this section provides an unsettling glimpse of daily reality in Cologne, a city that was largely supportive of Hitler.

|

|

|

The sections in People of the Twentieth Century were very much a product of the times, and no single section demonstrates this better than the one devoted to women, in which sitters are defined primarily by their relationships to men and children. As the section unfolds, wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters give way to the "elegant woman" and women "in intellectual and practical occupation." Family groupings emphasize the relationships among the subjects as well as between each sitter and the camera.

Here Ada Riphahn, the wife of Wilhelm Riphahn, who designed the Cologne Opera House, radiates a confidence appropriate to her age and social standing. The plush velvet chair, feathery dog at her side, and shimmering blouse are balanced by the strong lines of the drapery to create a richly textured portrait.

|

|

|

The array of writers, actors, painters, sculptors, architects, and musicians in the section of Sander's project dedicated to the artist attests to the breadth of his interests and friendships. German artist Ingeborg von Rath (1902–1984), shown here, studied at the School of Arts and Crafts in Cologne and traveled extensively throughout Europe. In 1927 she settled in Bonn where she first met Sander. In this image, her skilled hands are gently poised and her face deeply introspective, befitting her artistic specialization of portrait busts.

Sander's Cologne studio was a popular gathering place for young artists who engaged in lively debates about social and aesthetic concerns of the day, in particular the politically minded, left-wing artists known as the Cologne Progressives. These discussions helped advance Sander's idea to create a dynamic, cumulative portrayal of modern society. Although he was not perceived to be part of the European photographic avant-garde, Sander's photographs incorporated some of the thinking of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), an art movement in the mid-1920s that advocated a detached aesthetic toward subjects from everyday life.

|

|

|

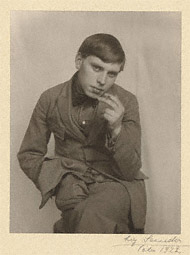

Sander captured the varied life of the city with portfolios dedicated to urban youth, street life, traveling people, festivities, servants, foreign workers, and the unemployed. Although the section avoids many of the extremes and depravities that have come to be associated with Weimar Germany during the period between the two world wars, it also included remarkable portraits of beggars and others who found their way to Sander's studio, and Jews who commissioned passport photographs that would allow them to escape Germany.

Within the portfolio on city youth, this image portrays Sander's friend Gottfried Brockmann (1903–1983), a young German painter associated with the Cologne Progressives who lived with the Sander family for almost two years. In contrast with another portrait of Brockman at his easel in the section on artists, this image underscores the contemplative nature of artistic practice.

|

|

|

The two girls in this photograph face the camera in a vague imitation of traditional posing principles. Their interlocking hands provide the emotional core of the image, compensating for their inability to make eye contact with the camera and with one another.

For the final section of People of the Twentieth Century, in which this portrait is found, Sander photographed "idiots, the sick, the insane, and the dying." Whether single figures or groups, indoors or out, these "last people" are presented in the same uncompromising way that he approached his other subjects. Remarkably, Sander never let his work devolve into a clinical exercise, but instead imbued it with a sense of engagement with and respect for his subjects. Together the photographs illuminate the cyclical nature of Sander's project, whereby in dying one returns to the earth and so the cycle begins anew.

|

|