Word and Image, the means through which Rudofsky communicated his ideas.

Bernard Rudofsky (Austrian-American, 1905–1988) was an architect, curator, critic, exhibition designer, and fashion designer whose entire oeuvre was influenced by his lifelong interest in concepts about the body and the use of our senses. He is best known for his controversial exhibitions and accompanying catalogs, including Are Clothes Modern? (Museum of Modern Art [MoMA], 1944), Architecture without Architects (MoMA, 1964), and Now I Lay Me Down to Eat (Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1980). He was also famous for his mid-20th-century Bernardo sandal designs, which are popular again today.

Drawn primarily from the Bernard Rudofsky papers at the Getty Research Institute, this exhibition analyzes his contributions to architecture, anthropology, fashion, and design, and illustrates his thinking through a diverse presentation of sketches, architectural models, travel notebooks, photographs, sculptures, fabrics, and footwear.

|

|

|

|

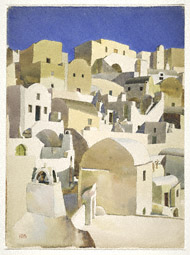

View of Oia, Santorini, Bernard Rudofsky, 1929

|

|

|

As a student, in 1929, Rudofsky traveled to Santorini, one of the Cycladic islands in the Aegean Sea, to write a dissertation about the barrel-vaulted houses found on this island. Here he encountered a lifestyle radically different from the one in which he had grown up in Austria. Rudofsky's experiences during this relatively short stay were the basis for all his future writings and exhibitions.

Travel became an important part of Rudofsky's life and work. He explored Europe and Asia Minor as a student from 1925 to 1929, moved to South America in the late 1930s, and settled in New York in 1941. After becoming an American citizen in 1948, he traveled regularly to Europe.

|

|

|

|

|

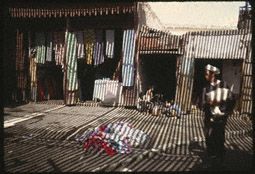

Fez, Morocco, Bernard Rudofsky, date unknown

|

|

Rudofsky's experience in new countries shaped his anthropological view of his surroundings. He made a large number of drawings, watercolors, and photographs during his journeys (images at right and above). In his travels, Rudofsky became fascinated with building design based on old traditions passed on from generation to generation without the input of an architect (also called vernacular or indigenous architecture).

Rudofsky's travels also provided the inspiration for his search for a new lifestyle in which all Western cultural inhibitions and restrictions—with regard to the ways we live, dress, bathe, and eat—would be alleviated by the heightening of sensual pleasures through design.

|

|

|

|

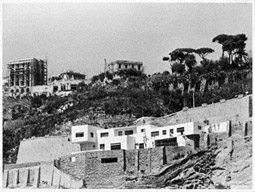

Casa Oro, Naples, Italy (view from below); Bernard Rudofsky with Luigi Cosenza, architects, 1935–1937

|

|

|

Rudofsky's first design efforts were in the field of architecture. He completed his best-known work, the Casa Oro, on a cliff overlooking the Bay of Naples, in collaboration with Italian architect Luigi Cosenza. It contains design elements that would distinguish his later home designs—a spatial arrangement integrated within the landscape, front courts, forms appropriated from traditional architecture, and an intimate atmosphere for the people living in the house.

Rudofsky was particularly interested in the architectural and cultural traditions of the Mediterranean and Japan. He felt drawn to the Mediterranean region's sybaritic, or sensual, attitude toward life, and its house designs with patios and protective walls blending interior and outdoor spaces. In Japanese architecture, Rudofsky admired the lightness of the wood, paper, and bamboo construction; the sparse, integrated furnishings; the generous, variable and modular spaces; as well as the close relationship between the traditional Japanese house and its natural surroundings.

|

|

|

|

|

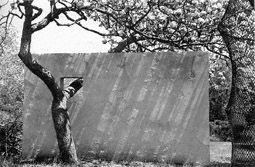

Nivola House-Garden (Garden Wall), Amagansett, N.Y.; Bernard Rudofsky with Costantino Nivola, architects, 1949–1950

|

|

Lacking an American architecture license, Rudofsky built very little after his move to the United States in 1941. Instead, he channeled his creative energies into the development and design of a series of pioneering exhibitions and books that challenged the field of architecture's traditional boundaries.

In the late 1940s Rudofsky did collaborate with Italian sculptor Costantino Nivola on a design for a house-garden in Amagansett, New York. Their concept recognized and valued the connection between buildings and nature. As seen in the image here, the intimate relationship between a free-standing wall and a tree, which grows through a sensitively designed opening in the wall, exemplifies Rudofsky's careful approach to man's intervention in nature.

|

|

|

|

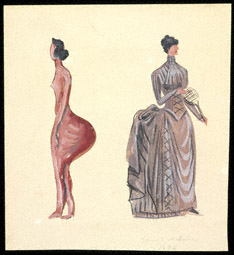

1886 Tennis Costume. Illustration from the exhibition Are Clothes Modern? Bernard Rudofsky, 1944

|

|

|

In 1944, Rudofsky curated and designed the exhibition Are Clothes Modern? for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The main visual strategy was the juxtaposition of traditionally ethnographic artifacts with similar-looking consumer products. The goal of the exhibition was to immunize the public against the persuasive power of advertising and the seductive appeal of continually changing fashions, thereby challenging accepted behavior and habits. At the same time, the exhibition was a covert architecture show through which Rudofsky continued to engage in the modern discourse on architecture designed for the individual rather than for the masses.

In the image above, Rudofsky juxtaposed a late-19th-century woman in a bustled dress with her undressed version in order to show what the female body would look like if it filled the dress.

|

|

|

|

|

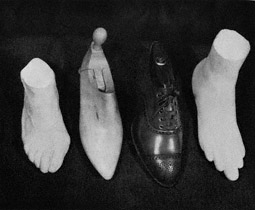

Rudofsky used this photograph to show how modern shoes do not match the shape of the human foot.

|

|

Together with his wife Berta, Rudofsky worked to promote a universal lifestyle of comfort through his clothing designs. He abhorred the fashionable tendency to cram fragile feet into what he considered personal torture devices masked by colorful leather patterns and alluringly shaped heels. In his book Are Clothes Modern? An Essay on Contemporary Apparel, Rudofsky included the illustration here with the following caption: "From left to right: Plaster cast of an adult's deformed foot which has taken on the shape of a shoe; wooden last; present-day shoe; plaster model of an imaginary symmetrical foot which corresponds to the shoe manufacturer's idea of human anatomy."

Rudofsky addressed this problem with the design of his Bernardo sandals (1946–1964), the most successful of his fashion designs. He preached the virtues of sandals as liberating footwear that transcend conventionality and ever-changing fashions. For Rudofsky, questioning one's lifestyle in order to improve it was fundamental to his unorthodox fashion designs.

|

|

|

|

|