|

Some of the jewels of the J. Paul Getty Museum's collection are featured in this exhibition, which explores the birth of modern drawing practice during the Italian Renaissance (1480–1550). During this period, drawing transitioned from a slavish part of the design process to an esteemed and independent activity.

Building on the innovations of Leonardo da Vinci, who popularized "brainstorm" sheets filled with ideas as well as the use of red chalk, artists explored new possibilities for the medium. In Florence and Rome the human figure was studied intensively through life drawing, while in Venice artists embraced the use of blue paper and the keen study of light and composition.

Venetian drawing sought pictorial effects through fragmented forms, depictions of light and shade, and a concentration on atmosphere over precise detail. Venetian draftsmen popularized blue-colored paper, which provided a useful midtone for such effects. A tradition emerged of small, meticulous drawings made in pen and ink or with a fine brush. Later, black chalk was adopted, allowing broad forms and intense contrast, a good match for the blue paper.

The simple beauty of the portrait above belies the extraordinary technical virtuosity with which it was made. Black chalk was used with almost infinite subtlety on the cheek, and in the shadows of the headdress a web of short, dancing lines render the texture. A few touches of white chalk below the eyes and at the edge of her right cheek provide hints of stronger light.

Andrea Previtali was a pupil of Venetian artist Giovanni Bellini, whose drawings Fortitude and Standing Man Wearing a Turban are also on view in the exhibition.

|

|

|

This is a preparatory study for an altarpiece in the church dedicated to Saint Zeno in Verona, Italy (see images on Wikipedia). The altarpiece was remarkable for its unification of figures, frame, and architecture. In this preparatory study for the left panel, a column is visible at right and a base at left.

Meticulous pen lines and hatching show the figures and drapery partly from below, as they would have been seen by the viewer.

Lighting was also important to Mantegna, who apparently installed a new window in the church to control the light on the painting.

|

|

|

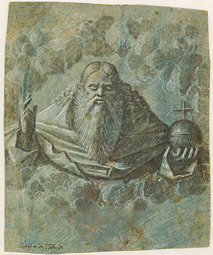

With one hand raised in blessing and the other holding a celestial orb, God the Father looks out from among clouds in this drawing by Venetian artist Vittore Carpaccio.

The composition is created almost entirely in light and shade. Black chalk and gray wash form the shadows, and Carpaccio's characteristic thin lines of white gouache stand as highlights, even picking out individual hairs on the beard.

This sheet was hurriedly prepared with blue, which can be seen from the brushstrokes at lower right. At lower center the vestige of an underlying red chalk sketch is still partially visible.

|

|

|

This intensely atmospheric drawing was made in preparation for a figure in Savoldo's altarpiece in the church of Santa Maria in Verona. Savoldo also used it in another painting depicting only Saint Paul.

Such a reuse demonstrates the vital role of drawings as workshop tools; they provided valuable records of paintings and were not discarded even after the picture was produced.

The sheet is extraordinary for its rich tonal effects achieved through the combination of various colored chalks.

|

|

|

In both Florence and Rome, drawing became a central activity in every artist's studio. Making sketches on paper was a vital component of artists' training and of every step in the creative process toward making paintings and sculpture.

Red chalk and metalpoint (using a metal-tipped instrument to work on specially prepared paper) were favored media. Life drawing—usually with readily available studio apprentices modeling as saints or martyrs—was used extensively to aid the realistic depiction of primarily religious scenes.

Using the gray of the prepared sheet as a midtone, Filippino Lippi drew this figure with a soft metal point, highlighting the study with thick, white gouache. His model was a studio assistant dressed as a saint, draped heavily with cloth and given a staff to hold. In this way Lippi could intensely study the fall of light on the drapery in preparation for his depictions of saints in his oil paintings.

The drawing is remarkably effective at conveying complex forms through areas of rapid hatching and deceptively simple white lines. On the verso, depicting Christ, a nude, and various figures, he drew a variety of sketches, treating the complex and permanent metalpoint medium with the freedom normally associated with a quill pen.

|

|

|

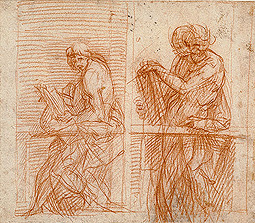

One of the most influential draftsmen of the Florentine Renaissance, Andrea del Sarto here rapidly threw down figures on the page. In two parallel sketches he studied a youth with a book standing behind a balustrade, particularly examining the positions of the arms.

In the head of the youth on the right, there are at least three pentimenti (minor changes) as the artist searched for the best placement: the head is shown looking up, looking straight at the book, and looking down over his shoulder.

|

|

|

This drawing, a study of a figure for a print, was created near the end of Raphael's short life (he died at age 37).

The focus of the composition is on the mass of soft drapery, rendered with gray wash and white chalk.

Seemingly effortlessly, Raphael conveyed volume through the subtle handling of light and shade. The raised arms are perfectly placed in space through the use of outlines that vary in strength and width.

|

|

|

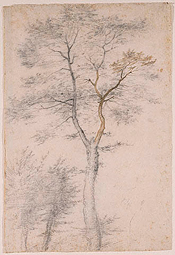

This is one of an important and rare group of drawings of landscapes and trees by Fra Bartolommeo, a Dominican friar who for many years was the principal painter of large altarpieces in Florence. As some of the earliest depictions of nature on paper, these studies mark the emergence of a new genre in draftsmanship.

In this example a tall tree with scattered foliage occupies the full expanse of the large sheet. Its bony, flecked structure is rendered in black chalk, with the branch at right carefully reworked with brush and brown ink. Broad, parallel strokes of chalk create an atmospheric, shaded effect, most evident on the two smaller, bushier trees visible at left.

|

|