Resurrection

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the rediscovery of Pompeii, along with the nearby towns of Herculaneum and Stabiae, propelled the birth and development of archaeology. For more than 300 years, excavations at the Vesuvian sites have advanced scientific reconstructions of daily life in the classical world. Simultaneously, they have influenced more fanciful reincarnations of antiquity, as contemporary values and ideas were superimposed on the distant past.

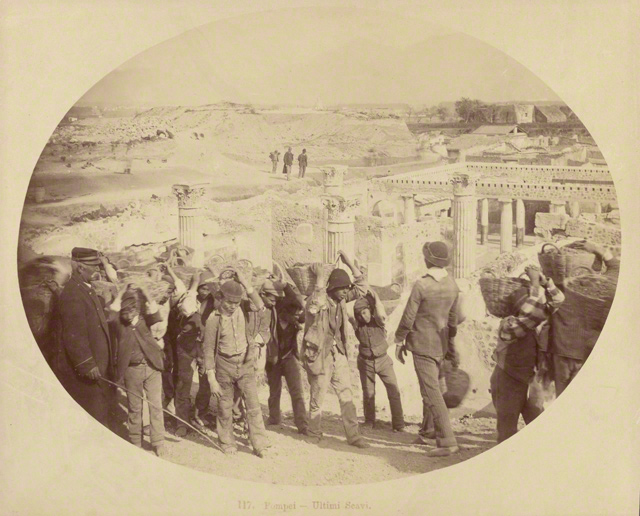

Excavations

This image documents the realities of digging at Pompeii, as forced laborers and prisoners were sometimes used to undertake the strenuous and perilous work of uncovering ancient remains. In the foreground, an overseer holds a long cane before a group of shabbily dressed boys carrying baskets of dirt. In the distance, two men gaze at the site, accompanied by a third figure, perhaps a servant. These two men—archaeologists or tourists—demonstrate the 19th-century divide between those who managed the excavations and enjoyed the discoveries, and those who actually cleared the ruins.

Romantic Ruins

Christen Schjellerup Købke visited Pompeii in 1838, making numerous sketches that he later used to create a series of paintings in his studio in Denmark. Although his paintings appear to be highly realistic and precise, Købke's onsite drawings reveal that he combined various architectural elements, plants, and animals to construct romanticized views of crumbling ruins. In this painting, he further heightened the sense of desolation by increasing the overgrowth of vegetation and introducing a herd of goats grazing in the distance, even though in his day Pompeii had already become popular tourist destination.

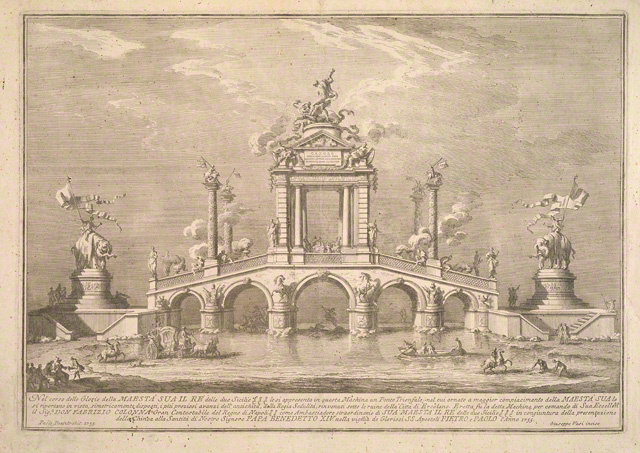

Fireworks and Politics

In 1749 and 1755, the princely Colonna family in Rome, representatives of the Bourbon monarchy in Naples, highlighted discoveries from Herculaneum during the Chinea, an annual religious festival that celebrated the wealth and power of the Bourbon kings. Each day of the festival culminated with pyrotechnic displays launched from elaborate temporary structures called macchine. At the 1755 festival, a large triumphal bridge was erected with a Latin inscription honoring "Charles, King of the Two Sicilies, advancer of the fine arts, for uncovering Herculaneum." The souvenir print shows the bridge adorned with invented artworks from Herculaneum. Thus, in this first public exhibition of "Herculanean" objects, the artifacts displayed were fictive.

Cabinet with Objects Excavated at Pompeii and Presented to Pope Pius IX in 1849. Walnut and glass with gilt brass letters, 74 13/16 x 55 1/8 in. (190 x 140 cm). Vatican Museums, Vatican City, 67902. Photo © Vatican Museums

Relics and Religion

Dignitaries of church and state have long exchanged and displayed artifacts to augment their status. This cabinet displays a selection of objects excavated during an 1849 visit to Pompeii by Pope Pius IX and given to him by the Bourbon king of Naples, Ferdinand II. Doubts have arisen, however, about the extent to which the dig was staged, and whether some of the artifacts were planted.The objects themselves are strikingly diverse in type and material, including items of marble, glass, bronze, terracotta, local stone, and lava. If pieces were chosen in advance, it was not to impress the pope with the most precious or aesthetically appealing treasures (apart from the marble sculpture), but to convey the breadth of finds, emphasizing their quality and variety.

Publication

The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection

By Victoria C. Gardner Coates, Kenneth Lapatin, and Jon L. Seydl

By Victoria C. Gardner Coates, Kenneth Lapatin, and Jon L. Seydl