|

|

|

Sour Orange, Terrestrial Mollusk, and Larkspur

Joris Hoefnagel

|

|

In the three and a half centuries (about 1450–1800) covered in this exhibition, artists increasingly took their inspiration directly from nature, attempting to capture every detail of insects, animals, flowers, and plants that became subjects of interest in their own right.

At the same time, scientists, natural historians, gardeners, and amateurs collected and analyzed elements of the physical world, disseminating this new comprehension of nature in prints and illustrated books. In these works, art and observation bridge two different modes of knowledge that came together in the Renaissance: the aesthetic and the scientific.

|

|

|

Joris Hoefnagel illuminated the page on the above right 30 years after the book was written by the scribe Georg Bocskay. Echoing the forms on top half of the page, Hoefnagel's natural minutiae were calculated to surpass the wonders of nature itself and to rival the scribe's virtuoso calligraphy.

|

|

|

Albrecht Dürer pioneered an appreciation of nature in all its diversity. Here he painted an accurate, life-size portrait of a male stag beetle. Cast shadows and the upward motion of its head create the illusion that the viewer is encountering a living insect.

Although the creature was closely observed, Dürer also made artistic choices that went beyond simply copying nature. Here, the beetle's spiky legs contrast the smoothness of the body, and the head rears up toward the right corner of the page, enhancing the menacing quality of the insect.

|

|

|

|

|

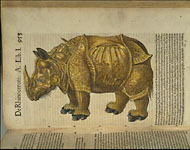

Rhinoceros

From Konrad Gesner, History of Animals

|

|

History of Animals, a five-volume work by the Swiss naturalist Konrad Gesner, was the most important zoological study of the Renaissance. Aiming to collect everything about animals that was then known, Gesner compiled a lengthy text and illustrated it with about 1,200 woodcuts. The prominence accorded to illustrations proclaimed the fundamental importance of observation.

However, images were not always rendered from firsthand observation, or completely realistic. This hand-colored illustration was made, as Gesner notes, after Albrecht Dürer's woodcut of 1515. The print was based on a letter and a sketch of a rhinoceros that had been sent from India to Portugal. But who has seen a mustard-yellow rhinoceros?

|

|

|

|

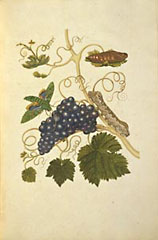

Wine Grapes and Caterpillars

Maria Sibylla Merian

|

|

|

Caterpillars in different stages of their life cycles populate this composition of grapes and vines drawn from nature. In 1699 Maria Sibylla Merian traveled to the Dutch colony of Suriname, on the north coast of South America. She stayed there for two years, keeping a journal and making sketches of exotic insects and plants. On her return to Europe, Merian published these scientific and artistic observations in this striking folio illustrated with hand-colored transfer prints.

For those who could not travel, the book provided views of faraway places and a surrogate collection of insects, plants, and animals.

|

|

|

Giovanna Garzoni worked for many important patrons throughout Italy and gained a reputation for her meticulous still lifes and nature studies on vellum.

Unlike most of the works in this exhibition, Garzoni's portrays a nature made both domestic and decorative. Beautifully composed and pictured on an intimate scale, her paintings are often filled with the typical fare of the Italian table.

|

|

|

|

View of a Squid

From Ippolito Salviani, History of Water Animals

|

|

|

Ippolito Salviani published the first major natural history treatise illustrated by engravings. He wrote in his preface that he wanted to create a work distinguished by its images. To this end Salviani hired a young painter, Bernardus Aretinus, and instructed him to go to the Roman markets in order to draw fish and marine animals directly from life.

The artist, together with an unknown engraver, created some of the most original and sumptuous natural history illustrations of the 16th century. Although the squid could be seen as a scary monster, this portrait presents a somewhat coy and engaging sea creature.

|

|