| Exhibitions | ||

| Collection | ||

| Education | ||

| Research and Conservation | ||

| Publications | ||

| Games | ||

| Public Programs | ||

| About the J. Paul Getty Museum | ||

| Museum Home

|

December 7, 2010–April 24, 2011 at the Getty Center

The J. Paul Getty Museum recently acquired photographs by some of the young artists emerging from the reinvented society that is present-day China. This exhibition is built around those acquisitions and loans from private collections. |

|||||||||||||

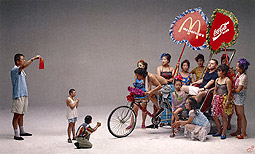

Wang Qingsong 王庆松 Wang Qingsong creates large-scale photographs that explore the rapid changes occurring in China, inspired by material grounded in classical Chinese art as well as in Western art history. His photographs comment on such topics as rampant consumerism, migration, globalization, and the influence of the West on Chinese culture. Capturing the contradictions of contemporary Chinese life, Wang Qingsong's staged compositions offer a critical consideration of the gulf between the traditional and the modern in China. About his photographs, he writes: "I wanted to create scenes in which old hopes are replaced with contemporary desires for money and power. To compare the past and present, I have reimagined old and new masterpieces in ways that reflect current social realities." His perspective reveals the paradoxes and confusions generated by what he ironically calls a "glorious life which is sweeter than honey." |

|||||||||||||

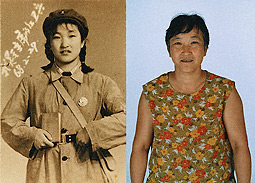

Hai Bo 海波 For the series They, Hai Bo creates diptychs dealing with the passage of time. Devoted to the reconstruction of the past, the artist makes photographs that are dominated by the themes of memory and change. Finding a photograph with the inscription "For the Future 1973.5.20" was the catalyst for this series, with the artist searching out each subject included in the photograph to restage the original. The diptychs juxtapose the past with the present, allowing the viewer to consider how the transformations that have occurred in China over the past decades have affected those who lived through them. Differences are captured in the pairings; youth is replaced by age, some of the sitters are absent, having died, and details such as clothing and hairstyles have shifted. Time does not stand still, as the single image might lead one to believe, and life outside the frame continues. |

|||||||||||||

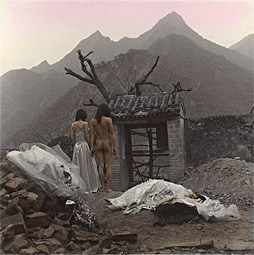

Rong Rong 荣荣 Rong Rong first documented the artists and the experimental performances they created while living in a neighborhood of Beijing known as the Beijing East Village. He later developed his own performances for the camera, producing a three-part body of work called Wedding Gown. Photographed in an abandoned village 40 miles from Beijing, the series uses the wedding dress as a metaphor for innocence and femininity. The hand-colored photographs evoke nostalgia for the past, while the figures enact a dreamlike narrative of death, cleansing, and potential rebirth. Rong Rong, the lone nude figure, moves through the site as if searching for something that cannot be found. |

|||||||||||||

Liu Zheng 刘铮 Employing nudity in his photographs, Liu Zheng opposes the Chinese state's repressive sexual mores. Historically, the nude is not depicted in Chinese art to the extent that it is in Western art, and during the Cultural Revolution it was forbidden. Contemporary artists and others have defied this taboo by including nudity in their practices to challenge authority and what is deemed acceptable. Liu Zheng's photographs reference turn-of-the-last-century late 19th-century prints through their sepia toning and scratches to the negative around the edge of the image. By overturning imagery from earlier stage and film productions, he creates an alternative way of looking at the past. |

|||||||||||||

Song Yongping 宋永平 Song Yongping, a first-born son, sought to balance his artistic career with care of his invalid mother and father as part of his expected duty. In 1998 he began photographing them in a series called My Parents. Using a confrontational approach to portraiture, these images combine performance with elements of everyday familial life. Karen Smith, a writer and art critic based in Beijing, described the photographs as "...a testimony to family bonds, and a sad glimpse into the lives of the masses caught up in the tidal wave of change in China today." The strength of this work is in its collaborative nature. Song Yongping, while tending to his parents' needs, was given the opportunity to honor them by sharing his art making with them. In recording the eventual loss of his parents in 2001, he created a lasting testament to their lives. |

|||||||||||||

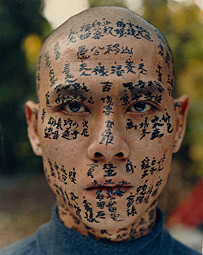

Zhang Huan 张洹 One of Zhang Huan's most powerful works, Family Tree was created two years after he left China to live and work abroad, leaving behind potential persecution as well as family and friends. Dealing with issues of cultural identity, familial relationships, and self-expression, this installation creates a moving image of the isolation felt with the loss of one's past. The artist had three Chinese calligraphers cover his face with poems, tales, and family names from his homeland, animating the traditionally silent portrait through language and performance. |

|||||||||||||

Qiu Zhijie 邱志杰 In the series Standard Pose, Qiu Zhijie explores the historical significance of the posturing found in the poster art and operas of the Cultural Revolution era, which helped maintain Communist Party control over the Chinese population. Using such slogans as "Learn from the workers" or "Long live the dictatorship of the proletariat," the posters celebrated Communist ideology through liangxiangliangxiang (operatic-style frozen poses) and props such as flags, Mao Zedong's Little Red Book, guns, hammers, and lanterns. Jiang Qing, Mao's wife, promoted the program of revolutionary operas that set patriotic plays to music. The figures in Qui Zhijie's photographs dress in contemporary Western clothing, and reenact these poses. The narrative is vague, yet it directly references the idea of the Cultural Revolution. Without the party attributes and rhetoric, the heroic poses represent the unfulfilled promises of the past. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||