Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins

Ancient Mesopotamia, centered in present-day Iraq, occupies a unique place in the history of human culture. It is there, around 3400–3000 BC, that all the key elements of urban civilization first appear in one place: cities with monumental infrastructure and official bureaucracies overseeing agricultural, economic, and religious activities; the earliest known system of writing; and sophisticated architecture, arts, and technologies.

These developments were concentrated in southern Mesopotamia, where the dominant ethnic and linguistic group until about 2000 BC was the Sumerians, famous today for their hero-king Gilgamesh of Uruk, the treasures found in the Royal Tombs at Ur, and the strikingly beautiful statues of Gudea, ruler of Lagash. By at least 2700 BC, the Sumerians lived alongside Akkadians,

whose king Sargon established the first lasting Mesopotamian empire, and whose Semitic language evolved into the dialects of the Babylonians and Assyrians. It was those cultures, adapting and extending the Sumero-Akkadian heritage, that built the great cities of Babylon and Nineveh, famed for their towering ziggurats, temples, palaces, and city walls; composed evocative creation myths, epics, hymns, and poems; and laid the foundations for future mathematics and astronomy.

For some three thousand years, Mesopotamia remained the preeminent force in the Near East. In 539 BC, however, Cyrus the Great captured Babylon and incorporated Mesopotamia into the Persian Empire. Periods of Greek and Parthian rule followed, and by about AD 100 Mesopotamian culture had effectively come to an end.

First Writing

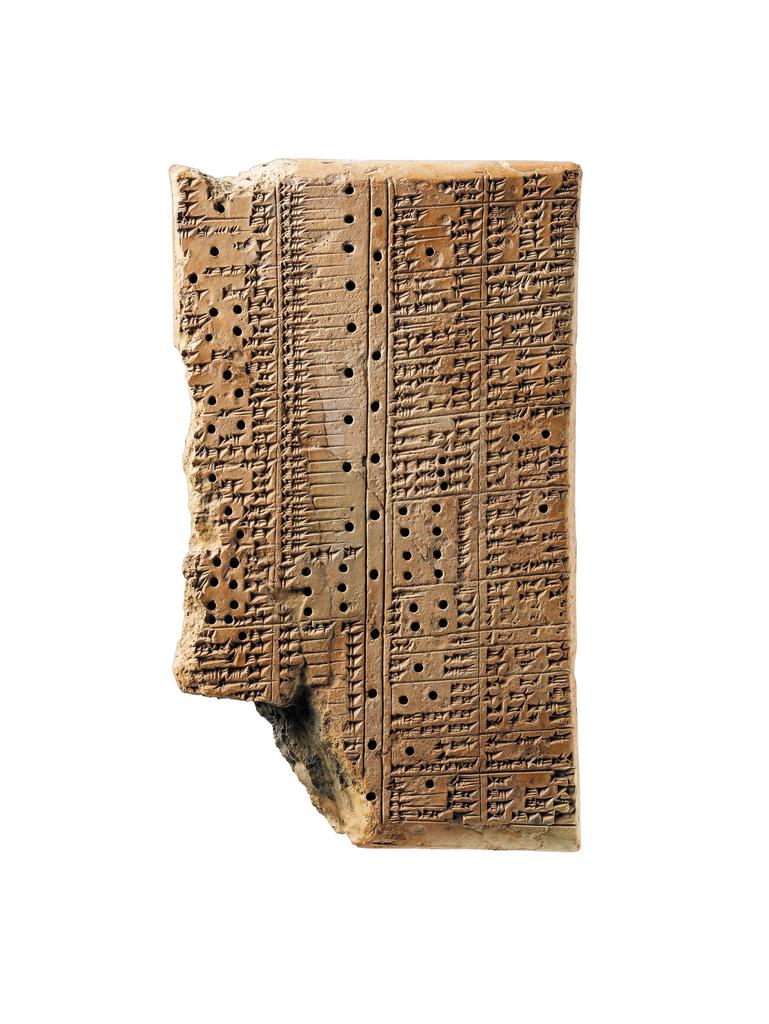

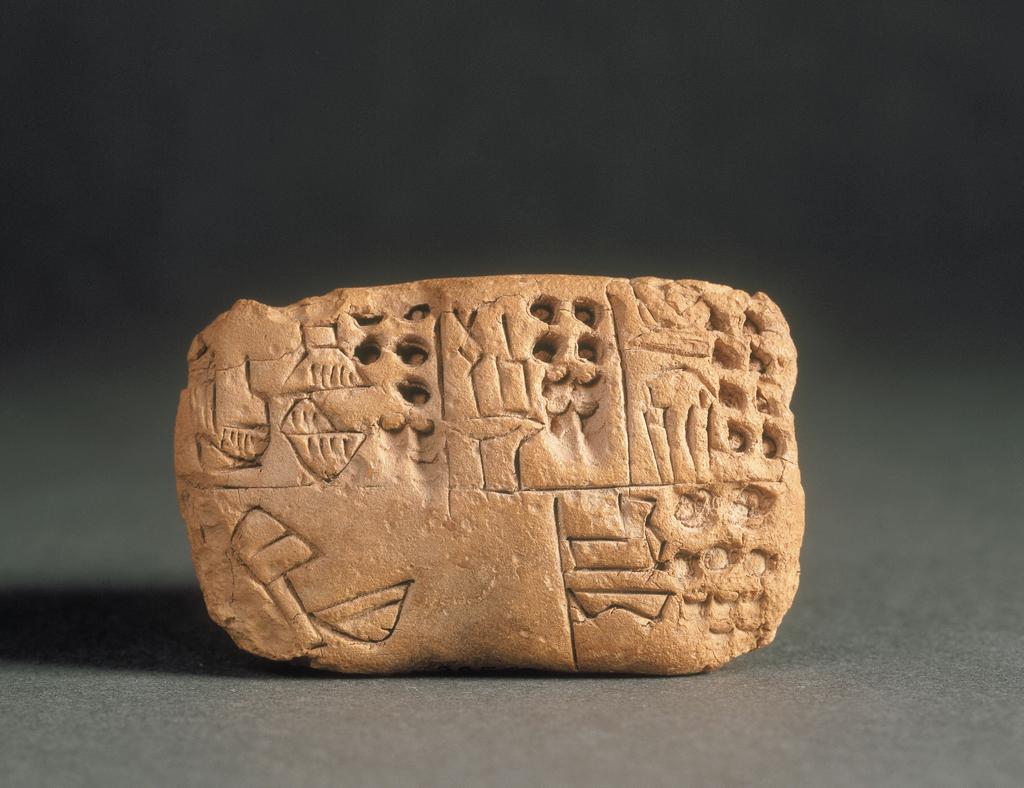

The earliest known writing emerged in southern Mesopotamia around 3400 BC, originating as a system of pictographs that evolved by 2600 BC into the distinctive wedge-shaped script we call "cuneiform." It was used initially to record the Sumerian language, and from about 2400 BC Akkadian, which split into two dialects, Assyrian and Babylonian, around 2000 BC. Over the next two thousand years, the use of cuneiform scripts—both the Mesopotamian version and new forms adapted or invented to write some fifteen other languages—spread to Iran, Armenia, Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and Egypt. For much of this period, Babylonian remained the international diplomatic language between the region’s "great kings." Cuneiform finally died out in the late first century AD, overtaken by the simpler alphabetic scripts of Aramaic and Greek.

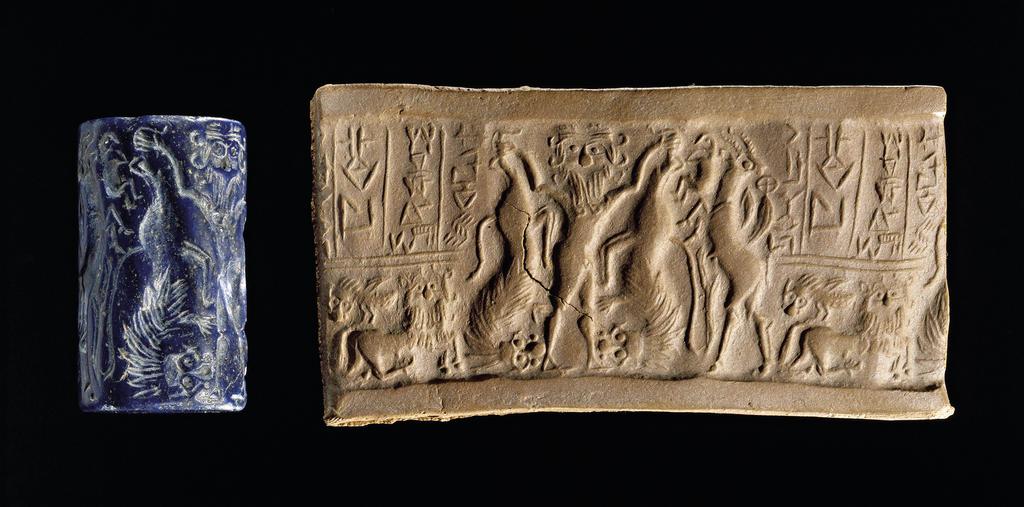

The vast majority of cuneiform writing was inscribed on clay tablets, which could also be impressed with a seal that acted like a signature. The hundreds of thousands of texts discovered by archaeologists include royal inscriptions, law codes, treaties, and literature, as well as everyday records such as receipts, contracts, letters, and incantations that reveal the intimate details of Mesopotamian social, religious, and economic life to an extent unmatched by any other ancient culture.

Extensive libraries of cuneiform texts were kept in temples and palaces, where scribes copied and recopied canonical compositions for millennia. Some kings, such as Shulgi of Ur (ruled 2094-2047 BC) and Ashurbanipal of Assyria (ruled 668-627 BC), claimed to read many languages and to be able to write cuneiform themselves.

First Cities

In the late fourth millennium BC, the first settlements that clearly qualify as cities emerged in Sumer (southern Mesopotamia). Preeminent among these was Uruk (biblical Erech), which by 3000 BC had grown into a walled city of over two square miles, with around a hundred thousand inhabitants. The economic basis of this transformative urban growth was intensive irrigation agriculture, requiring rigorous canal maintenance that was directed by the major temple estates.

The early cities of Sumer boasted monumental temples and palaces, decorated with statues of gods, kings, and worshippers. They were also centers of innovation and learning, where priests trained in sacred rituals, divination, exorcism, astronomy, and mathematics; where praise poems and mythological tales celebrating rulers and deities were studied and copied for posterity; and where law codes were created, international treaties were struck, and financial contracts were signed.

Some cities—notably Agade (location unknown), Ur, Babylon, and Nineveh— became imperial capitals that were renowned and feared throughout the ancient world. Indeed, when Alexander the Great conquered Mesopotamia in 331 BC, Babylon was still regarded as the most spectacular of all cities.

First Kings

According to Sumerian creation myths, kingship "descended from heaven," and the gods determined the order in which cities and their rulers held sway. A bearded figure known today as the "priest-king" appears in art around 3300 BC, but it is not until about 2700 BC that texts explicitly refer to rulers, who are titled en (lord), lugal (king, literally "great man"), or ensi (governor), according to local tradition. The ruler’s primary obligations were to lead in battle, to ensure the favor of the gods through temple building and regular offerings, to maintain the city walls and irrigation canals for agriculture, and to enforce justice.

The Sumerians were organized as a patchwork of city-states until around 2340 BC, when Sargon of Akkad established the first true and lasting empire—one that all later Mesopotamian kings would seek to emulate. Eras of strength and empire under the Third Dynasty of Ur (2112-2004 BC), the Babylonian kings Hammurabi (ruled 1792-1750 BC) and Nebuchadnezzar II (ruled 605-562 BC), and the kings of Assyria (880-612 BC) alternated with periods of invasion by foreigners from the Iranian highlands (Guti, Kassites, Medes) and tribal nomads from the northwest (Amorites, Aramaeans) —but these too adopted and sustained Mesopotamian culture. The conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great in 539 BC marked the end of native control of Mesopotamia and its incorporation into even larger empires ruled by the Persians, Greeks, and Parthians.