|

From wicked caricatures to wry satirical observations of social or political injustice, drawings have harnessed the power of humor for centuries. While some works were intended as intimate objects to be viewed only by individuals or small groups, others were made into prints with a wider agenda.

Just as social structures and art have changed through the centuries, humor in drawings has varied to fit the tastes of different periods. This exhibition is selected from the Museum's European drawings collection—along with several loans from the Huntington Library—to demonstrate how artists in previous centuries used the immediacy of drawing to make their points. While many of these works are still funny today, aspects of some of them may now seem curious or even distasteful.

|

|

|

Drawn humor could be biting, or simply a gentle nudge. Over the centuries, artists have particularly delighted in caricature. Caricature exaggerates the characteristic features of the human figure for amusement or criticism. The word derives from the Italian verb caricare, meaning "to load or charge."

The well-judged pen lines and delicate washes of this drawing highlight the man's awkward, bird-like features, from his beakish nose and spindly legs to his giant, duck-toed feet. The figure's meager shadow emphasizes his isolation, further increased by the absence of any setting. The man's puffy wig, turkey-wattle cravat, and oversize coat add to his ridiculous appearance. Drawings such as this were avidly collected in 18th-century Venice.

|

|

|

Innuendo exploits the comic potential of double meanings, often with the help of a written caption.

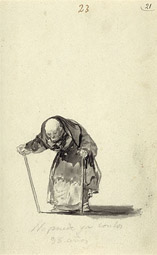

In this image, a frail old man, isolated and placed low on the empty page, hobbles along with the aid of two canes. As is often the case with Goya's drawings, an inscription in Spanish (translated in the work's title) holds the scene's meaning, both suggesting the elderly mans mental and physical frailty and hinting at his sexual impotence. This sheet, drawn when Goya was in his mid-70s, may be a meditation on the artist's own increasing age.

|

|

|

Playfulness harnesses humor to add a light touch to a more serious theme.

This drawing is a page from one of Edgar Degas' sketchbooks. In the sheet, which verges on caricature, Degas studied the faces of figures attending a funeral. Despite the occasion's somber mood, the artist exaggerated the amusing aspects of his subjects, from the protruding nose and sloped forehead of the man at bottom center to the pronounced noses of the three women in profile at upper right. This sketchbook also contains studies of dancers and singers as well as portraits of Degas's friends.

|

|

|

Comic Performance capitalizes on the many popular characters of the commedia dell'arte theater. With plots involving mistaken identity and disguise, adultery, unrequited love, and conflicts between young and old, the Italian commedia dell'arte was widely popular across Europe in the 1600s and 1700s. The unscripted plays were performed by troupes of traveling actors portraying stock characters. These characters and the themes of the commedia dell'arte became staples of French and Venetian art of the 1700s.

At the center of this stage-like composition is one of the most popular commedia dell'arte characters, the figure of Harlequin. Recognizable by his diamond-pattern pants, he draws up a contract as Mezzetin looks on. A young woman, still holding a quill pen in her hand, is led offstage by the Doctor while she looks desperately across the stage at her young suitor, who wears a displeased expression. This drawing was made in preparation for a print identified as Harlequin as Procurer, which may suggest that the woman has just been signed up for prostitution.

|

|

|

In northern Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and Germany, artists used humor to poke fun at social distinctions—sometimes with a moralizing intent—and deployed satire as a social weapon. Social and political satire generally denounces and ridicules the many vices, stupidities, and evils of humanity.

In this allegorical representation of the sin of avarice, de Gheyn attributed the human trait of greed to a realistically rendered frog. The frog bears a haughty expression while uncouthly grasping for the coins between its legs. With another foot, the frog holds a sphere, symbolizing the grasp of greed on the world. An avid student of nature, de Gheyn created a large number of allegorical and anatomical drawings of animals; this work may have once been a part of a larger sheet of studies.

|

|