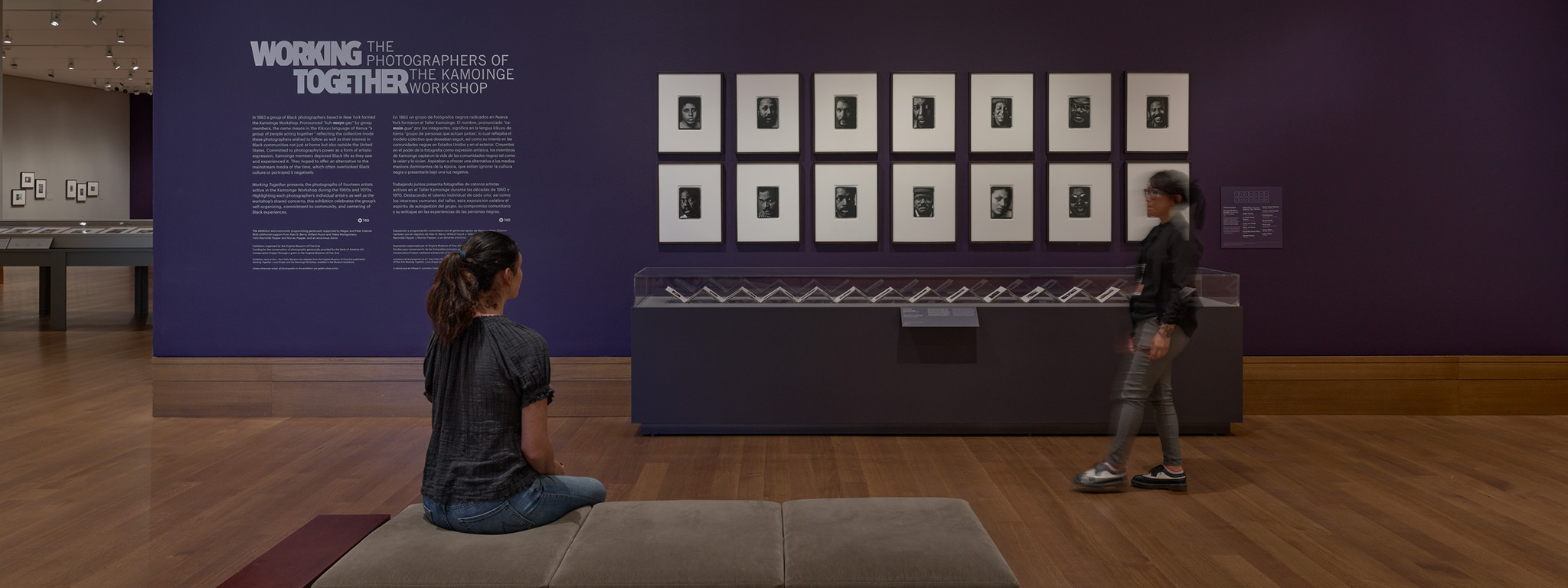

Working Together

The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop

Community

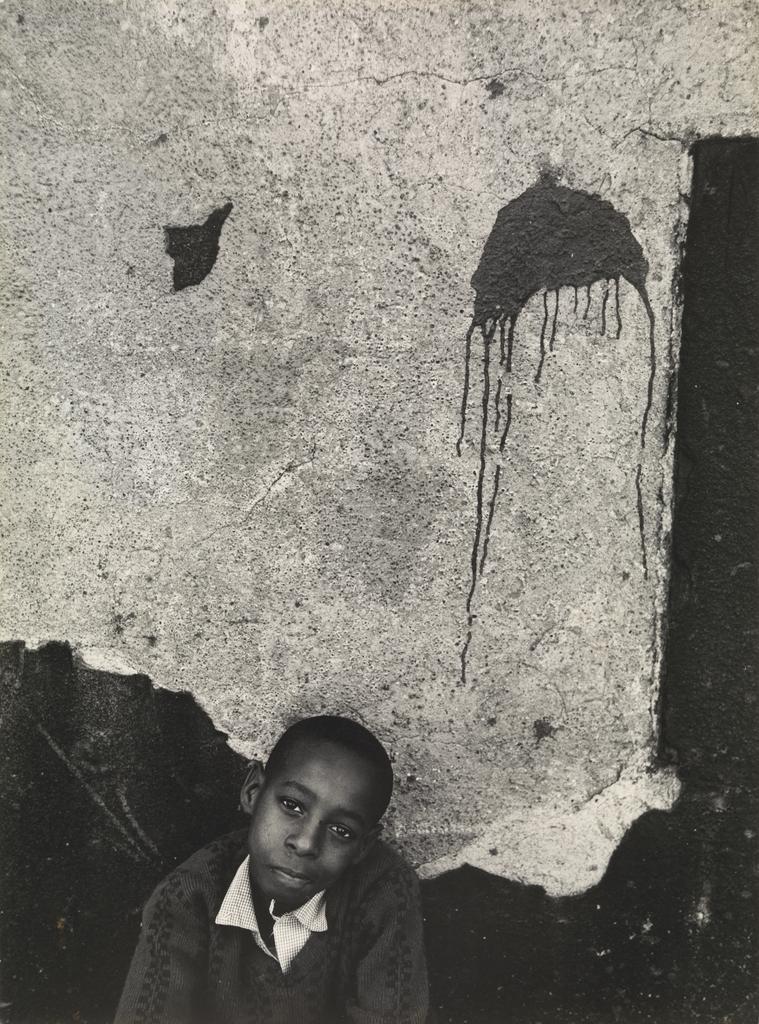

The Kamoinge Workshop began as a community of photographers who supported and encouraged one another. Within their first year, they also made a commitment to portray the communities around them. They introduced one of their early projects by explaining, “The Kamoinge Workshop represents black photographers whose creative objectives reflect a concern for truth about the world, about the Society, and about themselves.” Years later, member Louis Draper expanded: “Cognizant of the forces for change revolving around Kamoinge, we dedicated ourselves to speak of our lives as only we can. This was our story to tell and we set out to create the kind of images of our communities that spoke of the truth we’d witnessed, and that countered the untruths we’d all seen in mainline publications.”

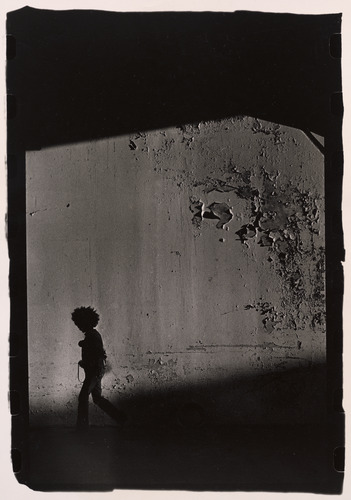

Mentorship

Kamoinge members taught photography in programs across New York City, from Brooklyn and Harlem to the Bronx, equipping a younger generation with the technical and philosophical knowledge they needed to portray their communities. Louis Draper noted that they were eager for “a sense of purpose other than individual acclaim; we wanted to serve.” In the late 1960s, Draper and Daniel Dawson taught a photography course for teens every summer, and Draper led a youth mentorship program in the Bronx. The photographs in this section of the exhibition document some of their students.

Civil Rights

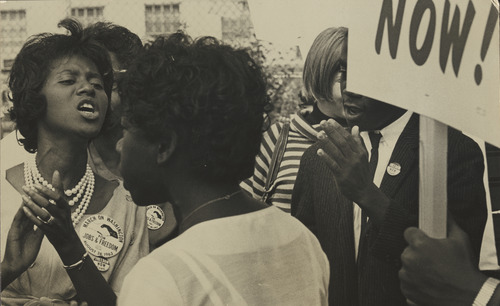

Although most Kamoinge members resisted being labeled civil rights photographers—a term they felt conjured images of firehoses and attack dogs—oral and written histories of the group emphasize that the collective formed in the midst of the civil rights movement. As Louis Draper described: “Many of the group had been a part of the March on Washington with Reverend King. Others had witnessed southern law brutality brought on by voting rights activity and sit-in demonstrations. Within a year’s time, these same volatile forces would propel many of us into engaged and enraged resistance.” Part of their resistance was to make images of Black Americans that were absent from the national conversation. Some members photographed leading figures and pivotal events of the civil rights movement but not necessarily to provide a journalistic record. Many created images reflected the theme of civil rights on a symbolic level instead.

"Like Jazz"

Music played an enormous role in the art of the Kamoinge Workshop. Jazz was a near-constant soundtrack for the group’s meetings, and musicians and live performances were the subjects of many of their photographs. Jazz also served as a metaphor for photography itself. Rhythm, timing, and improvisation are key elements in street photography as well as experimental abstraction. Innovative musicians such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane inspired Kamoinge artists, as did attending rehearsals and performances by figures as diverse as Mahalia Jackson and Sun Ra. These musicians moved the photographers to experiment and above all to hone their craft. Ming Smith characterized photography as “making something out of nothing,” adding, “I think that’s like jazz.”

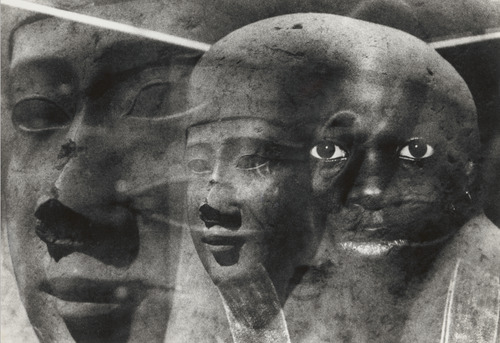

A Global Perspective

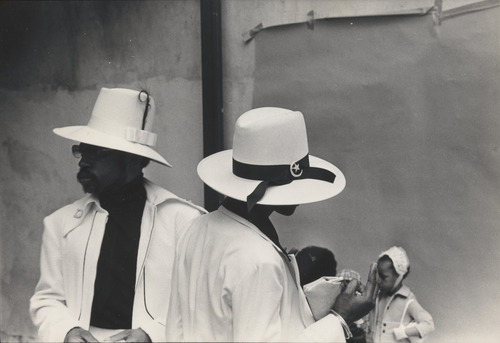

A significant factor leading to the formation of the Kamoinge Workshop was, as Louis Draper put it, “the emerging African consciousness exploding within us.” Even before most of the members began traveling internationally, their choice of a name from the Kikuyu people of Kenya emphasized their interest in Black experiences outside the United States. Kenya, which gained independence from colonial rule in 1963, the same year Kamoinge was founded, was frequently in the press during the group’s earliest meetings. The decolonization movement swept across the African continent from the mid-1950s through the 1960s, the same years that the US civil rights movement intensified. Many Kamoinge members traveled to African countries that had recently gained independence, and also to regions with significant diasporic communities. Some worked outside the United States on film projects or on assignments for magazines and in their off-hours made time for their own art. These travels expanded their sense of belonging to a global Black fellowship, however widely dispersed.

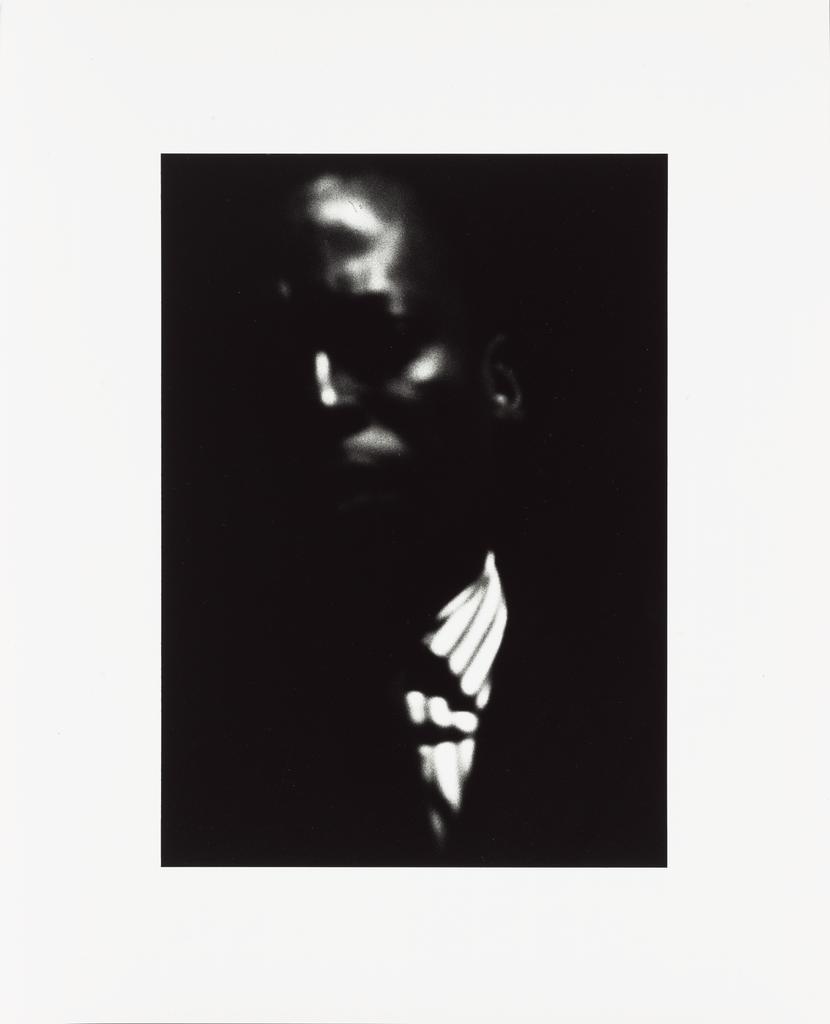

Shadows, Reflections, and Abstractions

Kamoinge has often been associated with street photography, but abstraction was also a crucial part of their work. By the time they joined the group, Louis Draper, Al Fennar, and Adger Cowans were already making abstract images in addition to more recognizably documentary pictures. In the late 1960s and into the early 1970s, many of the other members began to follow suit. Workshop photographers pushed themselves and the medium by experimenting with new forms and ideas. Through careful cropping, framing, and printing techniques, Kamoinge artists defamiliarized everyday sights such as puddles and clouds, asphalt, and weathered walls. Their images encourage greater attention to commonplace subjects—the reflective glass of shop windows, worn advertisements on city streets, a dirtied pile of salt—that might otherwise be overlooked. Much of their work with shadows and reflections centers Black bodies seeking a place for themselves amid the ebb and flow of daily life.

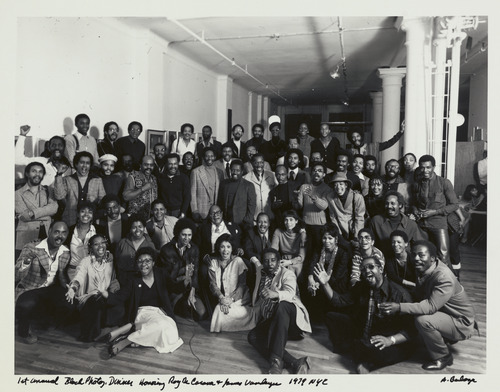

Kamoinge's Legacy

Kamoinge Workshop members supported not just one another but also the broader community of Black photographers. In 1973 Beuford Smith founded the Black Photographers Annual, a publication that helped bring attention to artists outside the Kamoinge circle. In 1978, other members started a group called International Black Photographers, which honored the work of photography elders and encouraged younger generations. Neither endeavor was part of the workshop’s official activities, but each grew out of the members’ ambition to serve and promote Black artists. Following their exhibitions in the mid-1970s, the Kamoinge Workshop neither organized exhibitions nor produced publications again until the mid-1990s. The group never disbanded, however, and the members remained close. They resumed formal meetings in 1992, applied for nonprofit status, and renamed themselves Kamoinge, Inc. A subsequent influx of new members energized the group as they continued the work that began in 1963.

Exhibition texts adapted from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts publication Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop