|

This exhibition loosely surveys more than 30 years of Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide's international career by highlighting major series produced in Mexico and the United States.

The breadth and depth of the selection has been made possible through the generosity of the artist, who opened her personal archive, and the magnanimity of Brentwood collectors Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser. They have followed Iturbide's work for more than 10 years and assembled a wide-ranging collection of her images, including many of the pictures created in the remote southern Mexican city of Juchitán, Oaxaca during the 1980s. Reflecting the extensive and discriminating Greenberg-Steinhauser collection, this important series, central to Iturbide's body of work, is a primary component of this exhibition.

|

|

|

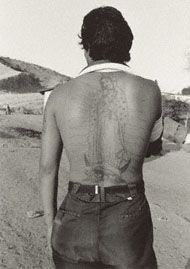

La frontera, the Spanish name for the border between Mexico and the United States, is an area of misunderstanding, unrest, and pervasive cultural cross-fertilization. In 1990, Iturbide paid special attention to the cholo culture in the outlying barrios of the border city Tijuana, Mexico. Here, the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, patron saint of Mexico, marks both walls and bodies, as seen in the image above.

|

|

|

|

Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas, Juchitán, Oaxaca (Our Lady of the Iguanas, Juchitán, Oaxaca), negative, 1979; print, mid-1990s

© Graciela Iturbide

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When the Mexican painter and printmaker Francisco Toledo contacted Iturbide in 1979 to ask her to photograph life in his native Juchitán in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, she found a project in which to indulge her desire to photograph the vitality of women. The small city in the narrow Isthmus of Tehuantepec is the most purely indigenous community in Mexico. The Zapotec women there are economically, politically, and sexually independent and have been idealized as a source of national strength for more than a century. Their bright, embroidered apparel, rich gold ornamentation, and elaborate coiffure identify them as part of the exotic-seeming Tehuana tradition.

Iturbide recalls how she obtained this picture: "This woman arrived [at the market] with iguanas on her head to sell, and I told her: 'Wait a minute, let me take your picture.' She had taken the iguanas off her head and put them on the ground but she put them back on her head for me."

|

|

|

|

|

Magnolia, Juchitán, Oaxaca, negative, 1986; print, 2005

© Graciela Iturbide

|

|

Iturbide's approach to photographing life in Juchitán was not the traditional distanced one of the documentarian. She chose to get well acquainted, to make the women "complicit" in the way she would photograph them. As Iturbide said herself about her experience among the "big, strong, politicized, emancipated, wonderful women" of Juchitán, "They adopted me in a way. They let me take my pictures and let me know about the various fiestas. I would go on pilgrimages with them....It wasn't only that they gave me permission to take photographs, they also suggested themes and showed me things. I discovered the Zapotec people through their eyes, and through my own at the same time."

|

|

|

|

Gallos, Juchitán, Oaxaca (Roosters, Juchitán, Oaxaca), 1985

© Graciela Iturbide

|

|

|

Iturbide's photographs from Juchitán also document the region's rich life of religion and ritual. Iturbide sees an analogy between these rituals and her own practice of taking photographs:

"It is the only way we have to transcend the mundane in life....Perhaps I have been marked by my religious education. When I was a girl, in order to get away from my family, I went to a convent to act. There was an atmosphere filled with disguises one can find years later in my work: the transvestites, the figure of death, the two faces of Janus. I don't pretend to mythologize indigenous peoples like many people believe I do, but what I love about them is their way of mythologizing the mundane. Maybe, when you come down to it, photography serves as ritual for me."

|

|

|

|

|

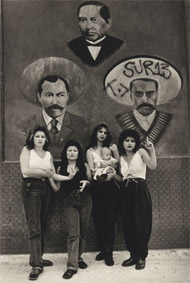

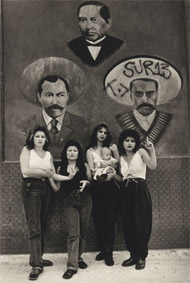

Cholas, White Fence, East L.A., negative, 1986; print, late 1990s

© Graciela Iturbide

|

|

In 1986 Iturbide was asked to participate in a photographic event to document the U.S. for the book A Day in the Life of America (1987). With an introduction from a friend, she made the acquaintance of a group of Mexican Americans living in the White Fence barrio of East Los Angeles.

The White Fence family befriended Iturbide and showed her the rituals and painted walls of their local cholo culture, which identified them as something other than Mexican or American. The 1980s cholo fashion—men wearing chinos or jeans with sleeveless white T-shirts or plaid Pendletons, longish hair sometimes in a hairnet, and evident tattoos, and women in tight jeans, halter tops, and heavy makeup —was heir to the pre-World War II Mexican pachuco, or zoot-suit attitude. Along with this costume, there was often signing, tagging (or graffiti), and other gangster activity passed back and forth across the U.S.Mexican border.

|

|

|

|

Danza de la cabrita, la Mixteca, Oaxaca (The Goat's Dance, La Mixteca, Oaxaca), 1992

© Graciela Iturbide

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

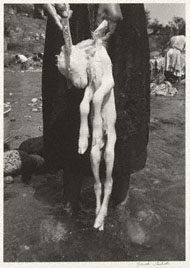

In the northern part of the state of Oaxaca, La Mixteca, goats have been herded since the Spanish arrived. A ritual that involves the slaughter of goats has continued from that time through the end of the 20th century. Iturbide witnessed this annual ceremony at the hacienda of Santa Maria in El Rosario, near the town of Huajuapan de León.

One part of the ritual is the dancing of the goat. This custom, no doubt related to the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac, includes choosing a goat to be spared from the slaughter, crowning it with a wreath of flowers, and selecting a boy to lead the rite by dancing with it atop his shoulders. Iturbide titled her images of the chosen goat La danza de la cabrita (The Goat's Dance).

|

|

|

|

|

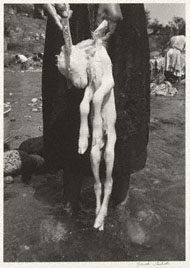

El sacrificio, la Mixteca, Oaxaca (The Sacrifice, La Mixteca, Oaxaca), 1992

© Graciela Iturbide

|

|

Iturbide visited the hacienda Santa Maria in 1992 with the writer Osvaldo Sanchez and the two collaborated on a book titled En el nombre del Padre (In the Name of the Father). The title comes from the prayer offered by the Mixtec Indians—hired to carry out the slaughter—before the killing begins.

Iturbide photographed the men, women, and children who had roles in the killing and butchering of the goats, an enterprise of both religion and profit. She describes her experience in the book:

"It was an erotic world for me, filled with the blood of sacrifice. The Indians make the sign of the cross and ask forgiveness before killing the goats. It's practically biblical, but erotic at the same time because everyone is very excited by the blood....I stayed and finished my work and ate mole with them afterwards (made with one of the goats that had been sacrificed). Through my camera I found myself immersed in a biblical world I found there and perhaps idealized or made up."

|

|