|

The Gothic period, stretching from about 1200 to 1350 in Europe, saw the construction of soaring cathedrals and the first universities. Cities teemed with students, tradesmen, aristocrats, and churchmen, who all clamored for illuminated manuscripts. This exhibition showcases a range of books, from lavish prayer volumes and Bibles, to illustrated scientific texts and romances.

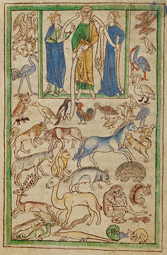

This image is from the Northumberland Bestiary. It is a major English Gothic example of the book of beasts, a collection of animal descriptions. In this illustration, the creatures receive their names from the biblical figure of Adam, suggesting that they all play a symbolic role in God's universe. The image's liveliness derives from the way the animals interact, from the horned creature charging a lion at left to the monkey mischievously staring out at the viewer from the page's center. The "tinted-drawing" technique, in which contours are drawn in brown ink and then accented with colored washes, favors delicate, curving lines that allow for natural poses, animated facial expressions, and softly draping garments.

On view during second installation: February 28–May 13, 2012

|

|

|

The increase of trade and the growth of cities throughout Europe during the Gothic period meant that both patrons and artists traveled more frequently, bringing with them artwork and styles that encouraged artistic discourse across regions. In the north, the style of manuscript illumination that emerged around 1200 was distinguished by naturalism tempered, by the end of the period, with courtly refinement. The art of ancient Greece and Rome as well as that of the Byzantine Empire influenced developments in southern Europe, resulting in the use of volumetric figures and stylized forms.

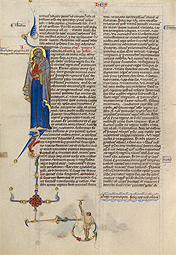

A standing Virgin Mary carrying the infant Jesus adorns the first initial of the Book of Esther in this Italian Bible. The Jewish queen Esther is renowned for acting as an intercessor on behalf of the Jewish people. The Old Testament book that bears her name recounts the appeal she made to the Persian king Ahasuerus in order to save the Jews from an impending massacre. For this reason, Esther was praised as a heroic model and associated with the Virgin Mary, whom medieval Christians saw as their intercessor with Christ. This manuscript highlights several characteristics of early Italian illumination, for example, the elegant poses, graceful drapery folds, and the green ground that serves as the undertone of the figures' flesh.

|

|

|

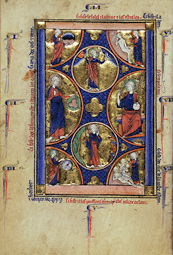

During the Gothic era, artists began to experiment with the design and format of the page in a variety of ways to increase its overall decorative effect. One of the most enchanting innovations was the extensive embellishment of the margins. These marginal elements sometimes relate thematically to the main image on the page, but often add a sense of humor. Other art forms also influenced the look of the painted page, such as stained glass, with its emphasis on geometric shapes and the predominant use of red and blue.

This page depicts episodes from the biblical Creation. Set as if golden light is streaming through the page, the image evokes glistening stained glass cathedral windows. Painted with generous quantities of gold leaf and costly pigments, the narrative features simplified compositions assembled in a series of circular and semicircular shapes with jewel-toned blues and reds adorning finely drawn figures. The story begins in the upper left hand corner where God creates the firmament, and ends at the bottom right where God creates Eve from Adam.

On view during first installation: December 13, 2011–February 26, 2012

|

|

|

In the early Middle Ages, manuscripts were largely produced by monks in monasteries for the use of the Catholic Church. During the Gothic era, however, the art of manuscript illumination became the province of professional artists living in rapidly expanding urban centers. Manuscripts designed to inspire devotion as well as to instruct and entertain were commissioned by a wide variety of individuals. Scenes reflecting aspects of daily life and society in the Middle Ages began to appear on the pages of a growing assortment of illuminated books— devotional works, law texts, scholarly literature, and romances—that might be written in either Latin or, for the first time, a local European language.

Contained within this initial N, delicately contoured figures swathed in vivid reds and blues serve as visual clarifications of local laws. The manuscript is the only known copy of a legal text established by King James I of Aragon to address all aspects of contemporary life in rapidly expanding Spanish cities. This scene illustrates the law forbidding women from conceding their dowry without the consent of a close relative. The upper half features a man returning the dowry to his wife and in the lower half, a judge informing a woman that her dowry cannot be given away if it would be detrimental to her children. What might have been a dry legal text, written in the language commonly spoken in the area, is vitalized by these vivid and skillful visualizations of the law.

|

|