|

This exhibition explores the tradition of manuscript illumination—book painting using brilliant colors and precious metals—in Germany and central Europe. A beloved artistic medium, illumination began with the flowering of book production under Charlemagne in the early 800s and continued even after the invention of the printed book in the 1400s.

Monks in monasteries produced the earliest illuminated manuscripts—often remarkably sumptuous liturgical books—for the ruling class, high-ranking ecclesiastics, and the monasteries themselves. By the 1300s secular artists and artisans started to produce books not only for these audiences, but also for an emerging middle class.

The stylistic range of the 24 works in the exhibition, including an illuminated printed book and several paintings, illustrates the extraordinary vitality of book painting over eight centuries.

|

|

|

Charlemagne, the Frankish king who was crowned emperor in 800, established a "new Rome" in northern Europe at Aachen and commissioned books that reflected its glory. He initiated a scholarly program of reform in culture and learning that enabled book production centers to flourish. The Ottonian emperors—the successors to the Carolingian rulers—also were great patrons of manuscript illumination and the monastic centers that produced them, such as those in Reichenau, Saint Gall, and Regensburg.

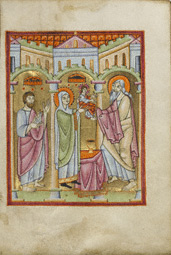

This illumination depicts the blessing for the feast of the purification of the Virgin. It adorns a page in a benedictional, a book containing blessings that the bishop recited at Mass on the most important feast days of the church year. The book was illuminated in Bavaria, probably at the Benedictine monastery of Saint Emmeram in Regensburg for Bishop Engilmar of Parenzo (present-day Poreč in Croatia).

|

|

|

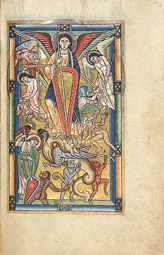

The term Romanesque refers to the revival of art and architecture based on ancient Roman models. Romanesque illumination flourished in Germany in the late 1000s and 1100s. New artistic centers emerged, producing manuscripts typically decorated with geometric forms arranged in bright, intricate patterns.

The missal, a service book for the Mass, was introduced in the late 1000s. This illumination is contained in the Stammheim Missal, a masterpiece of German Romanesque art created by the monks of the Benedictine monastery of Saint Michael at Hildesheim. Here Michael (the patron saint of the monastery) is depicted battling evil in the form of a dragon and demons.

In the 1200s the Romanesque aesthetic gradually gave way to the Gothic style, characterized by figure types and settings grounded in the observation of human form, volume, and movement.

|

|

|

By the beginning of the 1400s, the growing wealth and power of older cities such as Cologne, and the emergence of other towns, such as Prague and Vienna, made cities increasingly important centers of artistic production. The court of Bohemia was based in Prague, which was one of the preeminent European urban artistic centers.

The late Middle Ages also saw a rapid rise in demand for books written in the vernacular (the spoken language of a region, as opposed to Latin) along with a tremendous increase in secular texts.

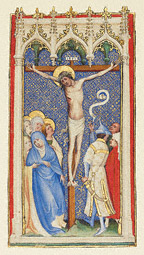

The Master of Saint Veronica was one of the finest painters in Cologne in the early 1400s.

He painted many altarpieces on panel, some not much larger than this work on parchment, one of only two known illuminations by him. The artist engages the viewer's empathy by focusing on Jesus's emaciated body and the sorrow of his mother, Mary.

|

|

|

|

|

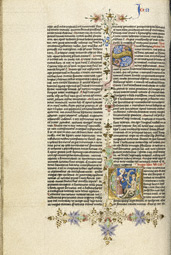

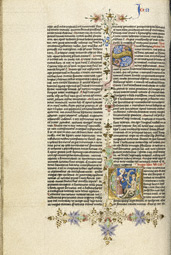

Initial V: Job Derided by His Wife in a Bible, Circle of Stefan Lochner, about 1450

|

|

|

|

By the 1400s, German manuscript illumination served a broad spectrum of society. Books ranged from sumptuous works in gold and precious materials on parchment to those written on paper and illuminated in a few inexpensive colors without gold or silver.

The art of printing first emerged in Germany in the mid-1450s, which is when the hand-written Bible shown here was made. This Bible was probably made by a cleric at Corpus Christi, an Augustinian monastery, for the Cologne Cathedral. Johannes Gutenberg (about 1390–1468), who designed and printed the first book using movable type, was most likely familiar with two-column manuscript Bibles such as this one.

|

|

|

For Christians, the Crucifixion is not simply the story of the death of Jesus Christ on the Cross, but also a story of the redemption of mankind. In the later Middle Ages artists sought to engage the viewer's sympathy for the story's human dimensions.

This large manuscript leaf—probably originally from a missal—shows angels capturing the blood of Christ in the chalice of the Eucharist, a popular theme in German book illustration.

Here the Crucifixion is depicted as if it were contemporary with the original owner's time. The background shows Jerusalem as a prosperous German town of the late 1400s, a walled city with several towers and a range of architectural styles. The setting made the distant historical event of the Crucifixion more immediate and relevant for the medieval viewer.

|

|

|

|

|

The Crucifixion, Albrecht Altdorfer, about 1520. Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

|

|

Albrecht Altdorfer of Regensburg, in Bavaria, was the leading painter of the Danube River valley in southern Germany. While he was not a manuscript illuminator per se, he made several dozen works on parchment.

This panel painting, which was recently conserved at the J. Paul Getty Museum, draws upon the medieval tradition of both painting and illumination with highly burnished gold backgrounds. By the early 1500s—the end of the period surveyed in this exhibition—such use of gold must have explicitly referred back to this time-honored practice.

A generous donation by the Paintings Conservation Council of the J. Paul Getty Museum supported the restoration of this work.

|

|