|

|

|

Gems from the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum

|

|

The beauty of carved gemstones has captivated collectors, connoisseurs, and craftsmen since antiquity. Precious markers of culture and status, gems were sought by Greek and Roman elites as well as modern monarchs and aristocrats.

This exhibition features intaglios and cameos carved by ancient master engravers along with outstanding works by modern carvers and works of art in diverse media that illustrate the lasting allure of gems.

|

|

|

The exhibition includes gems by several ancient master carvers, including Epimenes, Solon, Dioskourides, and Gnaios. These carvers sometimes signed their works, but the majority of classical gems are unsigned. With careful examination, anonymous intaglios and cameos can be attributed to known masters based on characteristics they share with signed gems.

|

|

|

Epimenes

Epimenes was a Greek carver active around 500 B.C. The exhibition includes one gem signed by Epimenes, along with four unsigned gems attributed to him. Similarities in material, technique, and style provide strong evidence for these attributions.

This gem with a standing youth is unsigned, but details such as the arm and leg muscles and the crosshatched hair with pellets representing ringlets are close enough in style to the only surviving gem signed by Epimenes to indicate that he carved it.

|

|

|

Solon

The ancient Greek gem carver Solon (active 70–20 B.C.) worked in Roman imperial circles, fashioning idealized portraits of the emperor Augustus and his sister, along with images of mythological figures. Solon's signature is preserved on five ancient gems, including the so-called Strozzi Medusa (also on view in the exhibition). His carvings gained great popularity in the 18th century due to the outstanding quality of that intaglio, which was copied by modern artists in diverse media.

More recently, several unsigned stones, including the one shown here, have been attributed to his hand.

|

|

|

|

Diomedes and the Palladion by Dioskourides (detail), Bernard Picart, 1724

|

|

|

Dioskourides and Sons

Dioskourides (active 65–30 B.C.), a Greek master from Aigeai in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), is one of the few gem carvers recorded in ancient literature. He is mentioned by several Roman authors as the carver of the personal seal of the emperor Augustus (ruled 27 B.C.–A.D. 14). Dioskourides' fame led later carvers to copy his works and forge his signature.

This intaglio showing the Greek hero Diomedes stealing the Palladion (a talismanic statuette of the warrior goddess Athena) is among the finest of all gems that survive from antiquity. In a field of just a few centimeters, Dioskourides convincingly rendered details of a dynamic, living body, clearly distinguishing skin, muscle, bones, and even fingernails.

In 1856 the gem was mounted into a bandeau with a pseudo-Renaissance enamel setting.

|

|

|

|

|

Satyr, Hyllos, 10 B.C.–A.D. 10

|

|

Dioskourides' sons, Eutyches, Hyllos, and Herophilos, followed him in the gem-carving trade.

This cameo by Hyllos depicting a satyr—a part-human, part-horse or -goat companion of the wine god Dionysos—shows the finely detailed carving that is characteristic of his and Dioskourides' work.

|

|

|

|

Mark Antony, Gnaios, 40–20 B.C.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gnaios

Although he signed his gems in Greek, the ancient carver Gnaios (active 40–20 B.C.) actually had a Latin name, Gnaeus. This does not mean that he was Roman, for Latin names were sometimes adopted by Greek artisans. The exhibition includes all four gems bearing Gnaios's signature that survive from antiquity—stunning intaglios of rulers and mythological figures.

This intaglio of the Roman general Mark Antony (83–30 B.C.) softens the harsh features seen on coins with his image. It may be a posthumous portrait commissioned by his daughter, Cleopatra Selene (40 B.C.–A.D. 6), whose husband, the North African king Juba II, was an avid gem collector. The gem was set into a ring in the 19th century.

|

|

|

In antiquity, gems were engraved with personal or official insignia that, when impressed on wax or clay, were used to sign or seal documents. Carved gems were valued not only for their distinctive designs, but also for the beauty of their stones, some of which were believed to have magical properties.

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, rulers, nobles, and wealthy merchants sought and traded classical gems, and carvers produced replicas and forgeries.

|

|

|

|

|

Frontispiece from the book Description of the Principal Engraved Gems in the Cabinet of His Serene Highness, the Duke of Orleans..., Augustin de Saint-Aubin, 1780

|

|

Gem Catalogues

Sumptuous engraved catalogues of gem collections were published in the days before photography. Like the gems they illustrated, these volumes functioned as luxury objects. The engravings in these books sometimes improve upon the already excellent carving of the gems themselves.

Louis Philippe d'Orléans (1725–1785), the great-grandson of King Louis XIV of France, published his gem collection in an elaborately engraved volume dedicated to his cousin King Louis XVI. The frontispiece, shown here, depicts the duke himself and also represents the superiority of gems over other art forms: in the foreground, two cupids inspect the contents of drawers pulled from a large gem cabinet, while symbols of architecture, sculpture, and painting are relegated to the upper right and lower left corners.

|

|

|

|

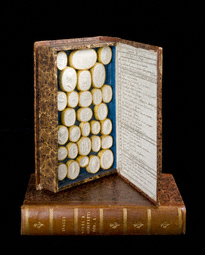

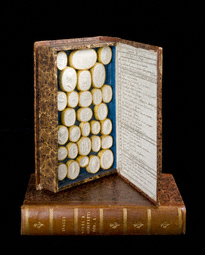

Daktyliotheke (Gem Cabinet) with Impressions, Workshop of Pietro Bracci, about 1825

|

|

|

Gem Cabinets

For those who could not afford gems, or for collectors who wanted to keep track of other collections, compilations of impressions were quite popular. Casts were shelved in large wooden cabinets or in cases formed as hollow books, which either opened to display their contents or were fitted with drawers. Such assemblages often combined impressions taken from modern gems with those of ancient ones.

The book shown here holds casts of both ancient and modern carved stones. Some of the impressions bear the signature "Pichler" for one of the Pichlers, a family of modern gem engravers (see below).

|

|

|

Since the Renaissance, gem carvers have attempted to equal and surpass their ancient counterparts. Because of the high demand for classical gems, some carvers, dealers, and collectors sought to pass off modern works as ancient. Some even forged the signatures of famous Greek and Roman carvers.

No scientific method exists for proving the antiquity of gems, and quality is no proof of authenticity. Thus it is usually some deviation in style or imagery that reveals a piece to be modern.

|

|

|

The Poniatowski Scandal

Prince Stanislas Poniatowski (1754–1833), nephew and heir of the king of Poland, amassed a collection of more than 2600 "ancient" gems in the early 1800s, including many bearing counterfeit signatures of famous carvers. Celebrated during his lifetime, the collection was later described as "a scientific deceit of such dimensions never before seen in the history of art."

This gem from Poniatowski's collection bears a counterfeit signature of the ancient Greek carver Dioskourides but has been attributed to 19th-century carver Giovanni Calandrelli.

|

|

|

Antonio Pichler and Sons

Austrian carver Antonio (Johann Anton) Pichler worked in Rome in the 1700s copying ancient gems. His son Giovanni also became an accomplished gem carver, as did Giovanni's half-brothers Giuseppe and Luigi and Giovanni's son Giacomo. Luigi was the most renowned: he received commissions from the Vatican and the French and Austrian courts to carve both classical and contemporary subjects.

This intaglio is modeled after a famous relief of Antinous (the beloved of the Roman emperor Hadrian) housed in the Villa Albani, Rome. The fact that the gem is signed "Pichler" in Greek indicates no intention to deceive but rather an emulative spirit, the artist vying with his ancient predecessors.

|

|

|

From the Middle Ages through the 19th century, cameos and intaglios were often used as decorative elements in a range of media. Gems were not only set in rings and pendants, but also mounted in the finely wrought covers of religious books and in reliquaries, altarpieces, and regal paraphernalia such as crowns.

Gems were also depicted on ceramics (such as a Sèvres cup and saucer in the Museum's collection) and in the margins of manuscripts. This detail from the margin of an Italian Renaissance manuscript features gems minutely rendered in tempera and gold paint.

Cameos and intaglios continue to be popular as decorative motifs in art, decor, and fashion today—evidence of the lasting allure of ancient gems.

|

|

|

|

|