|

|

|

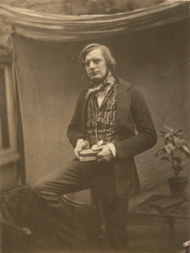

Self-Portrait, February 1852

Gilman Paper Company Collection

|

|

In only a decade, Roger Fenton explored the camera's full range of possibilities—from picturesque landscapes and lush still lifes to war photography and Orientalist fantasies. With this varied body of work, Fenton was one of early photography's greatest pioneers and advocates.

|

|

|

|

Moscow, Domes of Churches in the Kremlin, 1852

Gilman Paper Company Collection

|

|

|

Fenton trained as both a lawyer and a painter before taking up photography in 1851. He began his photographic career with subjects close to home: portraits of family and friends and views taken in and around London. But Fenton was adventurous from the outset, and in 1852 he accepted an invitation to travel to Russia. Recognizing that he was one of the first photographers to train his camera on Moscow and St. Petersburg, Fenton captured the distinct architectural character of each city.

Fenton climbed an adjacent tower to achieve this dramatic aerial view of the Kremlin complex. Many of his early photographs were made with a salted paper process, which creates subtle tones and rich textures. This print records light shining on a variety of surfaces, including gilded metal, rough roof tile, white plaster, and stone.

|

|

|

|

|

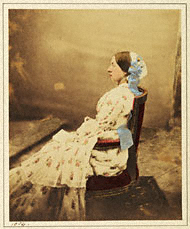

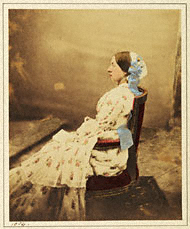

Queen Victoria, June 30, 1854

|

|

In 1854, Fenton was introduced to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert who subsequently commissioned him to make photographic portraits of the royal family. In this hand-colored portrait, Fenton presents the young Queen in profile against a plain background. The portrait is modest and informal, and like all of Fenton's royal portraiture, was intended for a private audience rather than for public display.

The Queen and Prince became England's most eminent photography enthusiasts, and Fenton maintained an invaluable relationship with the Queen for several years. He was invited to photograph her family at Buckingham Palace and other royal residences, and the Queen and Prince purchased several Fenton photographs of military exercises and still lifes. The Queen also lent support to the Photographic Society, of which Fenton was a founder.

|

|

|

Fenton traveled in 1853 to the Crimean peninsula, then part of the Russian Empire, where England, France, and Turkey were fighting a war against Russia. The publisher Thomas Agnew commissioned him for this assignment, but Fenton also received informal royal support, which gave him unprecedented access to the English campaign. He produced several hundred portraits and images of encampments and battle sites, that became the first extensive photo-documentation of any war.

To avoid offending Victorian sensibilities, Fenton did not photograph the dead and wounded. Yet his most celebrated photograph from Crimea alludes to the devastation of war. On this featureless landscape, the cannonballs, so plentiful that they first appear to be rocks, metaphorically stand in for the casualties on the battlefield.

|

|

|

|

|

Roslin Chapel, South Porch, 1856

Gilman Paper Company Collection

|

|

|

|

Landscape and architectural subjects provide a continuous thread running throughout Fenton's photographic career. Fenton spent part of each summer traveling in a wine merchant's van—converted into a mobile darkroom—in England, Scotland, and Wales. Inspired by preservation efforts in France, he documented many of England's abbeys, cathedrals, and country houses.

Fenton generally began photographing a building by making distant studies to establish its setting, and then creating more detailed views. By opening doors on both sides of this Scottish chapel, he recorded not only close-up detail but also a miniature landscape of distant fields.

|

|

|

Several years after his return from the Crimea, Fenton staged a series of photographs in his London studio, using objects he may have collected on his travels. This series of about forty photographs featured friends and models acting out scenes of the "exotic" East. Fanciful imagery with Orientalist themes were immensely popular in mid-century England. These images were hardly accurate depictions of the Islamic world—a world fearfully characterized by Europeans as sensual, indolent and luxurious—but nonetheless were widely accepted at face value.

Fenton filled this scene of Near Eastern entertainment with ornate objects, furnishings, and costumes to provide an aura of authenticity. But the camera's claim of truthfulness is undermined by the visible strings keeping the woman's hands aloft for the long exposure.

|

|

|

|

|

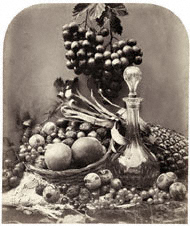

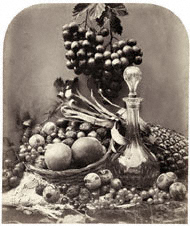

Decanter and Fruit, 1860

RPS Collection at the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford

|

|

|

|

In the late 1850s, Fenton continued to produce and exhibit landscapes and architectural studies. He also added another subject to his repertoire—still lifes. His lush images of fruits, flowers, and game were a conscious effort to elevate photography to the status of fine art. Derived from the Dutch tradition, still-life painting was immensely popular in England at the time, and Fenton's photographs closely resembled their painted counterparts.

In this composition from 1860, Fenton included an array of fruits and objects to demonstrate the camera's ability to record the varied textures of the world. Despite receiving glowing reviews for his still lifes, Fenton abandoned photography in 1862. Apparently dismayed by the growing commercialization of the medium, he sold off his negatives and equipment and returned to his law practice.

The exhibition is located at the Getty Center, Museum, West Pavilion.

|

|