|

This exhibition, featuring the oldest works of art in the Museum's collection, presents sculpture and vases from the Cycladic and other early Mediterranean cultures. What little we know about these societies comes in large part from the art they left behind. This exhibition explores not only the stylistic relationships among these pieces, but also what the objects can tell us about the people who created and used them.

Even though the objects were made in different areas of the eastern Mediterranean from about 6500 B.C. to 1650 B.C., they show similar styles and ideas, particularly in the abstract treatment of the human form. Because these works were made so long ago, no written records exist from the time, and there are often more questions than answers surrounding these fascinating pieces.

|

|

|

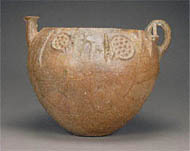

This large terra-cotta vessel from Cyprus belongs to a group of twenty known objects decorated with

scenes of daily life. These works provide a rare glimpse of the activities of early Cypriot Chalcolithic

society, and they suggest that some tasks that were essential to all members of the community were

cooperative endeavors. On this side of the bowl, a group of stylized figures is making bread. The

entire process is documented: grinding the grain for flour, kneading the dough, forming the conical

loaves, and then baking them in an oven. Because the two human figures on the other side of the vase

(see below) have identifiable male genitals, it is thought that the bread-making figures depicted here

are female.

|

|

|

|

Red Polished Ware Bowl (other side)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unlike the bread-making figures, the scene on the opposite side is harder to interpret because

it is not clear what the circular areas with conical objects represent.

Are they interior views of ovens with baking loaves that are connected to the bread-making scene? What

relationship do they have to the two male figures, the stag, and the smaller quadruped? Could they be

animal traps into which the stag will be driven? Or could this depict metal production, with conical

piles of copper ore being leached of its soluble salts? None of these interpretations is completely

satisfactory because not all of the scene's elements are included in any one.

|

|

|

The vast majority of Cycladic figures are female. Among the existing examples only 5 percent

depict men, and most of these are engaged in special activities (like the harpist below). The profile

of this figure reveals a particular interest in the female body and its condition. The swollen abdomen

indicates pregnancy. These figures raise a number of questions: Do they depict humans? Are the female

figures representations of a deity worshiped on the islands, perhaps a fertility goddess like the Cypriot

limestone statuette below?

|

|

|

This statuette of a seated musician is the only male Cycladic figure in the Museum's collection.

In contrast to the numerous images of females with folded arms, the few depictions of men often show

them engaged in some activity, such as drinking or playing musical instruments. In a preliterate society,

musicians played an important role not only as entertainers but also as storytellers who perpetuated myth

and folklore through song.

|

|

|

Much of the modern esteem for Cycladic figures (and their influence on Modernist art) is based on a

misconceived aesthetic premise: that the objects were created with the purity, abstraction, and

simplicity of the design and the blank white look of the marble that we see today. Originally, the

appearance of most figures must have been much more complex. Facial and anatomical details, and

sometimes garments, were rendered in bright paint. The figures were decorated with red, black, and

blue designs indicating jewelry and body paint or tattoos. Instead of abstraction there was colorful

realism. The addition of paint allowed for differences and variation within a rather uniform sculptural

style.

|

|

|

Since there is no marble on the island of Cyprus, the sculpture produced there is usually made of

local limestone. Unlike contemporary Cycladic images of females that are more upright, this figure appears

to be squatting, perhaps giving birth. Her curiously shaped breasts, which seem to symbolize

female genitals, imply that she represents a fertility goddess. The unusually large size of the figure

may indicate that it was used as a cult image. The careful repair made to the left arm in antiquity

suggests the statuette was a highly treasured object.

|

|