Imogen Cunningham

A Retrospective

The Wood Beyond the World

After her graduation from the University of Washington, Cunningham took a job in the studio of photographer and ethnologist Edward S. Curtis. She learned the platinum printing process there, and received a grant that allowed her to continue her studies in Dresden, Germany. On her return to Seattle, she began making soft-focus platinum prints with an ethereal dreamlike quality. Her work in this period was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement in art and literature, which called for renewal within the Victorian art establishment through spiritualism and an enhanced connection with nature. An epic tale set in a medieval forest, The Wood Beyond the World (1894) by William Morris, a leading figure in the movement, particularly sparked her imagination.

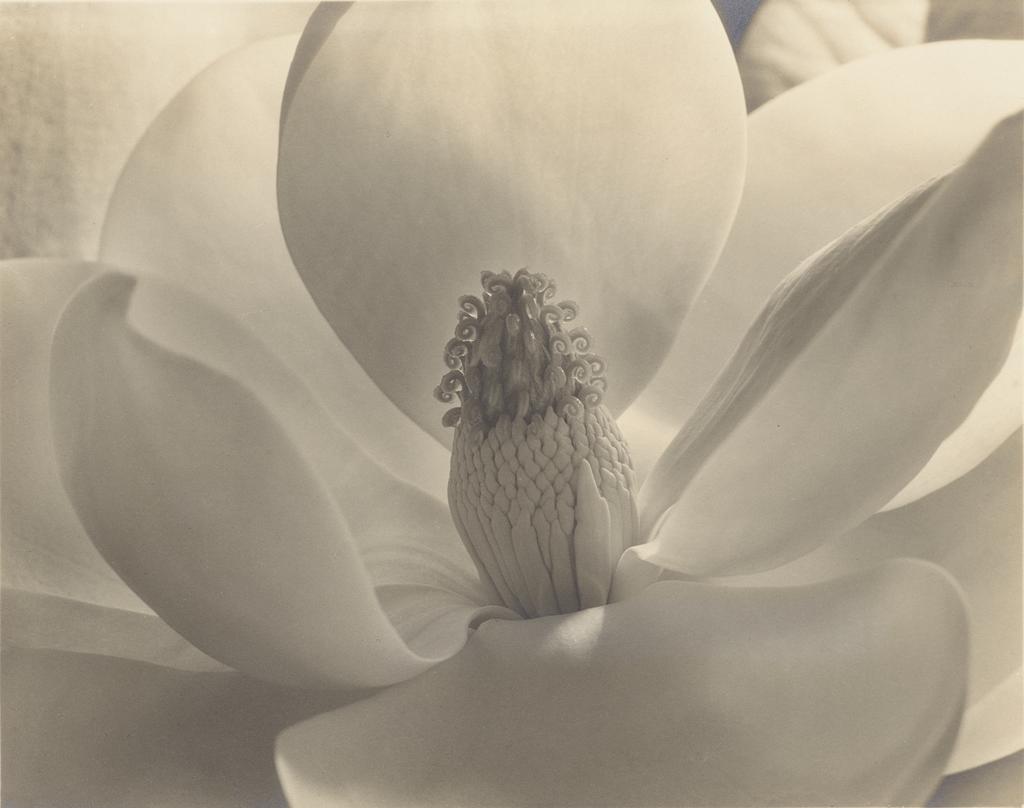

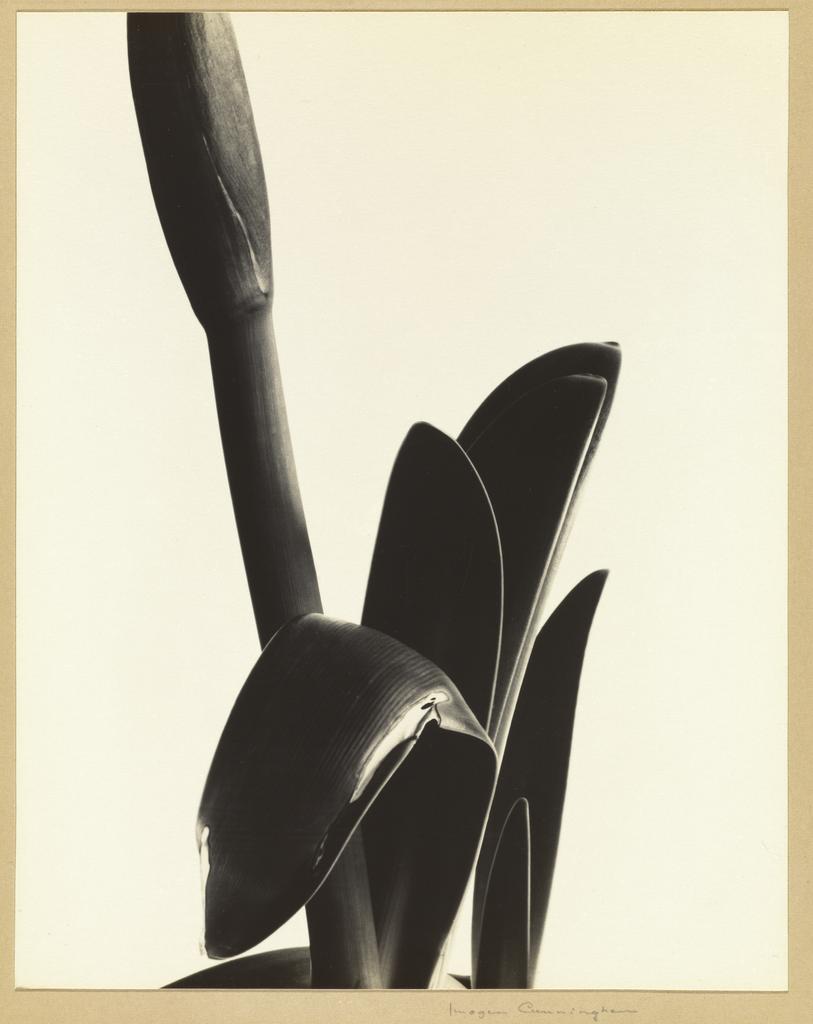

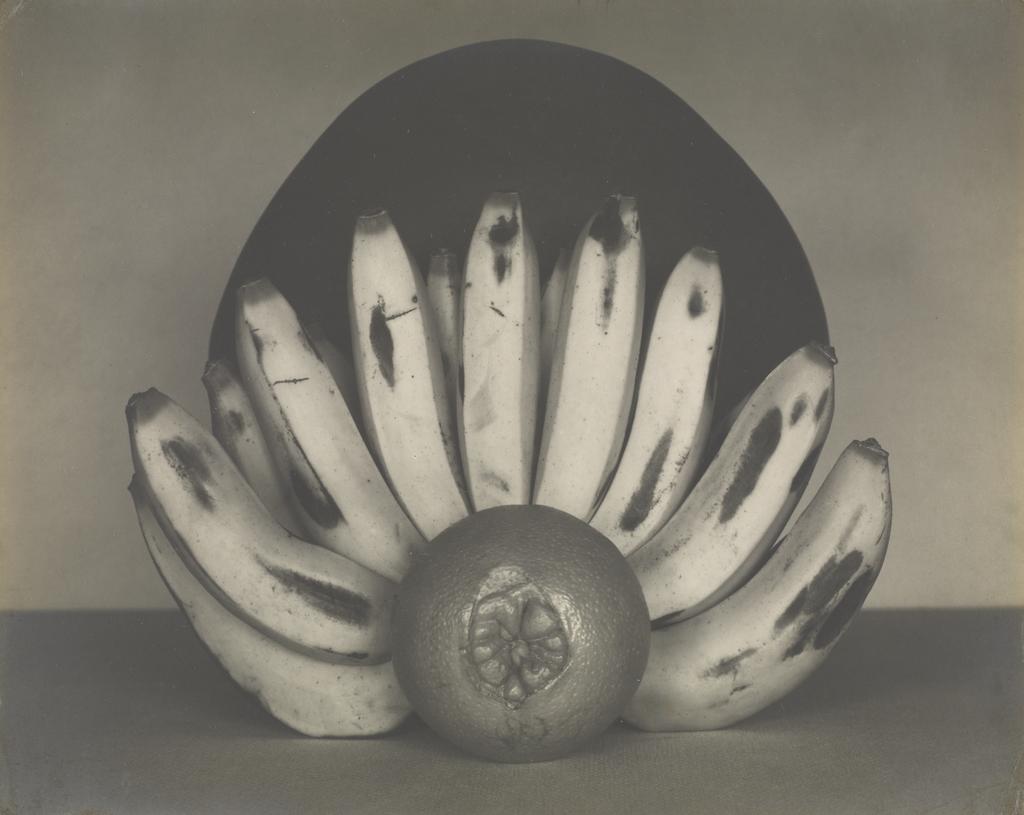

In Her Garden

After Cunningham moved her family to San Francisco in 1917, she turned away from soft-focus images and began to make sharply delineated pictures. She cultivated a garden, growing plants and flowers for a series of botanical studies, all while taking care of her three young sons. In 1929 the prominent photographer Edward Weston recommended that ten of Cunningham’s photographs be included in the seminal exhibition Film und Foto in Stuttgart, Germany. Although the show did not bring her financial success, it garnered international recognition for her as a leading American modernist photographer.

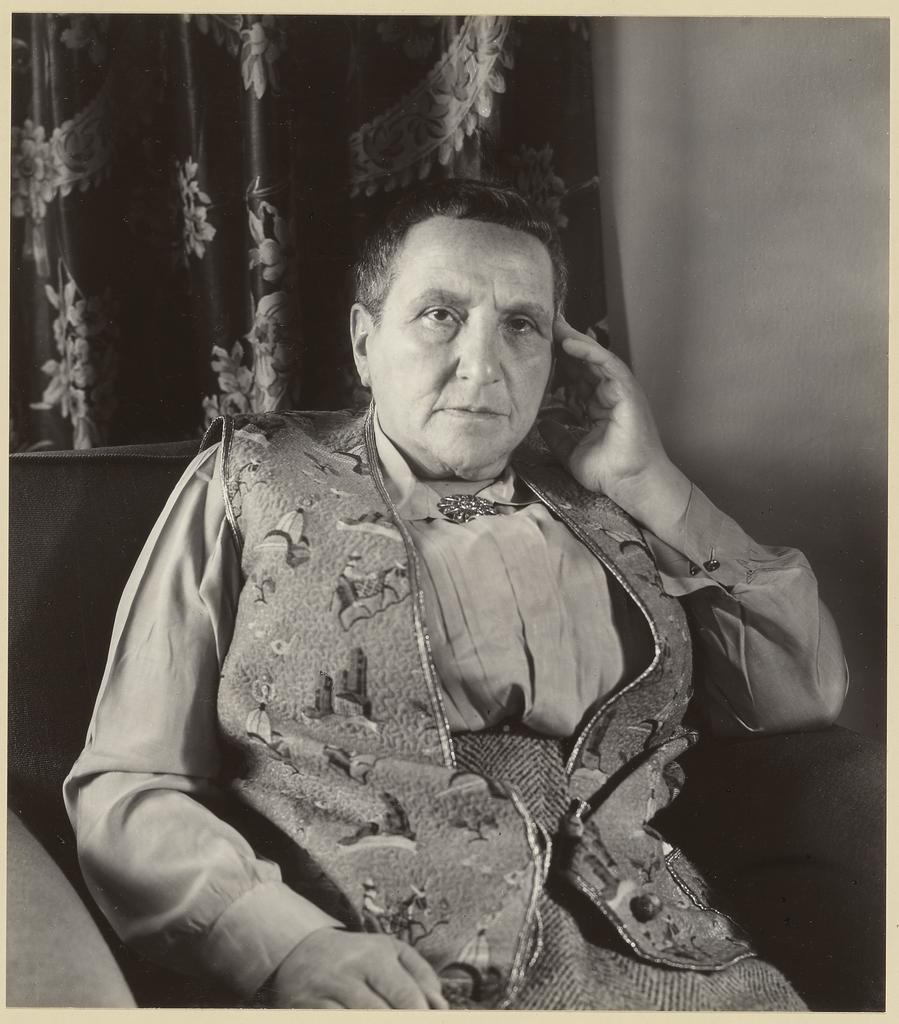

On the Portrait

When asked to describe the requirements for a successful portrait photographer, Cunningham replied, “You must be able to gain an understanding at short notice and at close range of the beauties of character, intellect, and spirit, so you can draw out the best qualities and make them show in the face of the sitter.” She would often engage her sitters in conversation until they relaxed, or ask them to think of the nicest thing they could imagine. She resisted indulging their vanity, however, and “face-lifting” was her word for the type of portrait work that required beautification—in her estimation an obstacle to a good likeness.

West Coast Photography

In 1932 Imogen Cunningham, along with Ansel Adams, John Paul Edwards, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke, and Edward Weston—all San Francisco Bay Area photographers—helped found Group f/64. (They adopted the name from the aperture setting on a large-format camera that would yield the greatest depth of field, making a photograph equally sharp from foreground to background.) The goal of this loosely formed association was to promote a modernist style through sharply focused images created with a West Coast perspective or sense of place. The works presented in this gallery, created by Cunningham’s closest colleagues—all contributors to the Group f/64 legacy—demonstrate how the influence they had on one another defined the future of West Coast photography.

A Parting of Ways

In 1934 Cunningham’s marriage to Roi Partridge ended in divorce. Their three teenage boys, Gryffyd, Rondal, and Padraic, remained in the family home with their mother until they finished high school. Cunningham never remarried, and although she received the house as part of her settlement, the divorce was the beginning of three decades of financial difficulties. Without Partridge, Cunningham had to pick up the pace of her work to stay afloat. She took more commissions, made more portraits, and began teaching portrait photography to students in her home. Despite the added stress, Cunningham sought out ways to challenge herself.

Into the Street

In 1934, while in New York, Cunningham made what she called her first “stolen pictures,” documentary street photographs that she took while trying to hide herself and her camera from view. Her interest in street photography was renewed in 1946 when she met Lisette Model while they were both teaching at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute). Cunningham’s candid depictions of her subjects have often been described as gentler and more sympathetic than those by many of her contemporaries. Her “stolen pictures” capture people as they are and not how they look when they know they are being photographed.

A Network of Women

Cunningham was a woman of exceptional intelligence and talent, yet competing in a male-dominated profession posed a formidable challenge, particularly after Partridge divorced her in 1934 and she struggled to support herself. To make matters worse, Cunningham felt disparaged by some of her male colleagues, who occasionally downplayed her talent and influence. As a bulwark against the stress, Cunningham joined San Francisco Women Artists, a group organized to promote, support, and expand the role of women in the arts. Over the years Cunningham served as a resource for female artists such as Laura Andresen, Ruth Asawa, Alma Lavenson, Laura Gilpin, Dorothea Lange, Consuelo Kanaga, and Merry Renk, among others, providing advice, moral support, and essential connections throughout the art and business worlds.

The Light Within

In 1964 the photographer and editor Minor White devoted an issue of the influential magazine Aperture to Cunningham. In an elegant tribute, he described his own experience of the spell she cast over her subjects as a kind of inner light. The first publication dedicated entirely to Cunningham’s work, this issue of Aperture contained a selection of forty-four images dating from 1912 to 1963, representing her wide range of genres and styles.

Between 1965 and 1973 Cunningham served as a visiting photography instructor at the California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland; Humboldt State College, Arcata; the San Francisco Art Institute; and San Francisco State College. In 1970 she was awarded a Guggenheim Foundation grant of $5,000 to make prints from her old negatives. This prestigious prize marked a turning point in her long career, an acknowledgment that coincided with a rising interest among museums and enthusiasts in collecting photographs, both historical and contemporary.

After Ninety

When she was ninety-two, Cunningham started a new project, photographing people of advanced age. She estimated that this would take two years to complete, and she planned to publish the photographs in a volume to be called After Ninety. She began to seek out subjects, visiting them in their homes, in hospitals, and in convents. The project provided an outlet for her determination to keep active as well as a way to come to grips with being a nonagenarian herself. Cunningham died on June 24, 1976, and the book was published the following year.