|

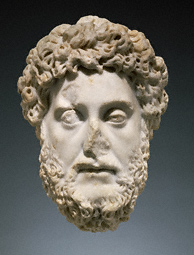

This exhibition focuses on an ancient marble bust of the Roman emperor Commodus (ruled A.D. 180–192). When the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired the bust in 1992, it was considered to be the work of an Italian sculptor active in the late 16th century. Today, however, most experts are convinced that the sculpture is ancient. The exhibition explores the statue's history and reveals how curators and conservators have established the bust's origin and date.

The style and carving techniques of the bust of Commodus are characteristic of the second century, as is the fringed cloak. A post-antique sculptor could have reproduced these elements, however, so the recent debate over the object's date has centered on its state of preservation. Mineral deposits remain in inconspicuous areas, suggesting that the sculpture was buried for a long period. Most of the surface was cleaned and some sections were recarved in modern times, which is typical for ancient works restored in the 1700s.

|

|

|

|

Head of Commodus, Roman, A.D. 182–190

|

|

|

As a prince of the Antonine dynasty, Commodus had his first official portraits sculpted while he was still a boy. New types of imperial portraits were created on the occasion of significant life events or to mark milestones in a political career, such as the bestowing of a title, the designation as prince, or the ascension to power.

The Getty bust, with its short beard, is a prime example of Commodus's fifth portrait type, which was created in the fall of A.D. 180, when—after the death of his father, Marcus Aurelius—Commodus became sole ruler. More than a dozen ancient replicas of this portrait type exist, and the Getty bust is among the finest.

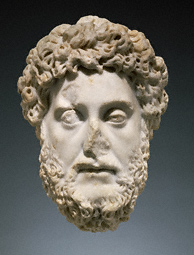

Shown here is an example of Commodus's sixth portrait type, which was created in the early A.D. 180s. Compared to the Getty bust, it depicts the emperor as an older man. He has a fuller beard, sunken cheeks, thinner lips, and pronounced folds around the nose and mouth.

|

|

|

|

|

Bust of Antoninus Pius, Roman, A.D. 138–161

|

|

Little is known about the Getty Commodus's provenance (history of ownership). The bust was acquired in the 1700s by the fourth Earl of Carlisle, who accumulated a significant collection of Roman marbles for his Yorkshire estate, Castle Howard. Documentation of his purchases is scarce, making it impossible to identify the proper sources of some works or to establish their earlier provenance.

The exhibition features three Roman portrait busts from Castle Howard, including the one shown here, that were acquired by Lord Carlisle around the same time as the Getty Commodus. The busts share four characteristics with the Getty Commodus: they are all in an outstanding state of preservation and of superior artistic quality; their sitters are all of the Antonine period; their surfaces show a comparable polish; and the figures all wear a fringed military cloak, or paludamentum.

Such similarities suggest that the busts have a common source, probably in Italy, and may even have come from the same archaeological context.

|

|

|

The Getty Commodus was previously thought to be a 16th-century or even later copy of a Roman original. The reason for this confusion—which affects the attribution of many sculpted portraits of ancient figures— is the ubiquitous phenomenon of making copies "after the antique" in later European sculpture.

During the Renaissance, rulers and aristocrats began to collect both ancient and contemporary portraits of Roman emperors, who served as models for their own system of power. Portraits of celebrated rulers such as Marcus Aurelius, Commodus's father and predecessor, were sought after and copied in the 1500s and later. Portraits of unpopular figures such as Commodus, known as a ruthless eccentric, were not in demand. It is therefore very unlikely that a Renaissance collector would have chosen Commodus to be sculpted as a large and prestigious bust.

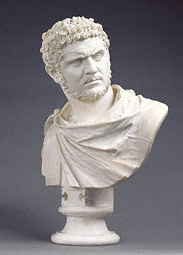

While sculptors in the 17th century imitated Roman portraits, attempting to capture sentiment and character, Neoclassical artists of the 18th century were interested in aesthetics and the revival of an antique spirit. The Roman bust became the ultimate model for sculpted portraits. To carve marble exactly like ancient artists did was the highest achievement. Artist Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, for instance, proudly signed this bust of Caracalla—a precise replica of the emperor's most famous ancient portrait, the Farnese Caracalla in the Naples Museum, of which numerous modern copies exist.

|

|