|

In 19th-century Paris, weekly journals employed teams of artists to churn out popular caricatures of Parisian life. The art world was a common target of satire for these publications, and the Salon—the annual juried art exhibition, sponsored by the French government—received special attention. This immense exhibition served as a kind of proving ground for artists and visual entertainment for the public.

Caricatures of the Salons appeared in abundance from the 1840s to about 1900. These Salon reviews in pictorial form poked fun at the yearly exhibition, from its dizzying display of thousands of paintings and sculptures, to the self-importance of viewers, to the prevailing mediocrity of the works. Much of the humor results from the clash between the Salon's growing irrelevance to contemporary life and the edifying role accorded to the fine arts in French culture.

|

|

|

A common target for ridicule in the caricatures of the Salon was the socially diverse public who attended the event. Honoré Daumier became the master of satirical images of the Salon public. He lampooned the public's various misreadings of art, their social pretensions and affectations, and their view of art as entertaining spectacle. In the image above, Daumier vividly represents the melee on Sundays, the day of free admission.

|

|

|

|

The Two Schools Face to Face, Bertall, 1867

|

|

|

Virtually every Parisian journal published reviews of the Salon that functioned both as guides to the exhibition and as serious art criticism. While the battle between the ancients and the moderns is an oversimplification of the issues that defined the field of art critical discourse, it was this highly politicized aesthetic debate that caricaturists most frequently targeted. In this battle, the representatives of academic traditions stood for high ideals and noble subjects drawn from the past, while representatives of Realism and other modernisms stood for commonplace subjects and contemporary life.

One embodiment of the Realist school was the fashionable Parisienne seen here. By the time this caricature was published, she had supplanted the peasant as the quintessential modern life subject.

|

|

|

|

|

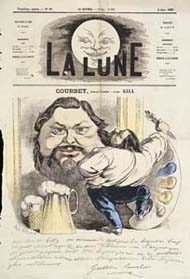

Courbet, André Gill, 1867

|

|

Nowhere did the ideological battle of the ancients and the moderns find deeper expression than in the public reception of the two most prominent Realists of mid-century: Gustave Courbet and Edouard Manet. Representing different types of Realism—peasant Realism and the painting of modern Parisian life—these artists experienced frequent rejections by Salon juries and derision from critics and the public alike during the years that they did show. Like all the Realists, they were admonished "for so obstinately reproducing subjects of offensive vulgarity, types without character, and scenes devoid of all interest." While Courbet apparently enjoyed his succès de scandale, Manet suffered under the negative publicity.

|

|

|

|

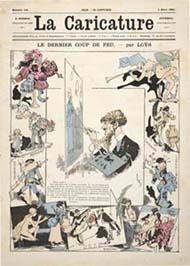

Late-Nineteenth-Century "Isms," Loÿs, 1883

|

|

|

One of the surest signs that the moderns would eventually triumph over the ancients was the persistent complaint among critics that "Grand Painting" was becoming increasingly banal and insignificant. The high ethical and political seriousness of allegorical, history, and religious painting was giving way to an emphasis on technique for technique's sake. History painters appeared to be losing sight of the subject matter. Their obsession with detail and costume, treatment of subjects in an anecdotal or ethnographic manner, and their appropriations and combinations of historical styles all provided fodder for the caricaturist.

Loÿs's caricature presents a classification of Salon painting that appeared toward the end of the century. Germanism, Naturalism, Little Soldierism, Idyllism, Modernism, Impressionism, Primitivism, Orientalism, Japanism, Fortunyism, and Academicism are illustrated through their clichés of subject matter and execution. Naturalism, for example (seen second from the top at the left), was known for its somber portrayal of beggars, peasants, ragpickers, and laundresses.

|

|

|

|

|

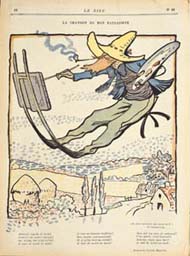

The Landscape Painter's Song, Lucien Métviet, 1895

|

|

By the 1890s, all of the clichés of Impressionist landscape were firmly in the public mind. These included the landscapist's obsession with working en plein air (outdoors), his slightly seedy image, his leftist politics, and his distinctive techniques for applying color.

Making rapid sketches of poplars, wheat stacks, and farmhouses, the arabesque figure of this plein-air landscapist soars above his own picture. All of the elements in this caricature refer to well-known Impressionist subjects and techniques. The wheat stacks may be a reference to paintings like Monet's Wheatstacks, from his series of paintings depicting the same subject at different times of the day and in different seasons.

See Monet's Wheatstacks—the type of painting mocked by this caricature. See Monet's Wheatstacks—the type of painting mocked by this caricature.

|

|

|

|

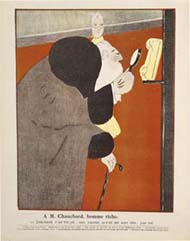

A Rich Collector, Paul Iribe, 1903

|

|

|

By 1900, the proliferation of independent exhibitions, coupled with the Salon's diminishing importance, helped to produce a new breed of art patron as aesthete. This breed represented a shift away from the notion of art's "higher" purpose, whether conceived by the ancients or the moderns of the 19th century. In the spirit of Gautier's doctrine of art for art's sake, the patron-aesthete emphasized the purely decorative function of art. Rarity and preciosity were valued over "sincerity." Art in this context was more about the refined tastes and financial speculations of a select audience than it was about the edification or provocation of a general public like the Salon public of Daumier and his contemporaries.

|

|