Camille Claudel

Introduction

A trailblazing woman artist working in France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Camille Claudel (1864–1943) defied the social expectations of her time to create forceful sculptures of the human form. Her innovative works of art treat the universal themes of childhood, old age, love, and loss with an expressive intensity in a variety of genres, materials, and scales. Collectors and critics immediately recognized Claudel’s talent, but today her art remains little known outside France. Her career has often been interpreted through her dramatic personal life, which included a complicated relationship with her mentor, the sculptor Auguste Rodin, and mental health issues resulting in a thirty-year confinement in a psychiatric institution. Presenting Claudel’s major sculptures in the United States for the first time in over two decades, this exhibition explores the full range of her work, emphasizing her technical virtuosity and powerful voice.

Portraits

Portraiture is an important genre in Claudel’s body of work, and busts were the first artworks she presented to the public at the Parisian exhibitions of the early 1880s. Critics and collectors noticed her talent at once, and influential French art journals featured her portrait drawings in their pages. Claudel was only twenty-three when one of her works, a bust of her sister, entered a French museum, gifted by Baroness Charlotte de Rothschild. In the nineteenth century, women artists often gravitated to portraiture, selecting their sitters from a close circle of family and friends. This genre did not require working from professional nude models, an artistic practice that was controversial for women at the time. Claudel excelled at capturing the likeness of her subjects, depicting individuals at every stage of life with powerful emotion and empathy.

In Rodin’s Studio

Encouraged by Camille’s first teacher, the sculptor Alfred Boucher, the Claudel family moved from Nogent-sur-Seine, east of Paris, to the capital in 1881 so that their daughter could study art. Claudel attended classes at the Académie Colarossi, an art school rare in that it allowed women to learn anatomy by studying nude models. She joined other women sculptors in renting a studio in the city, where Boucher came to critique the group’s work. At around nineteen, Claudel began working in Rodin’s studio to complete her training. Her involvement with the great artist, which lasted about a decade, was complex: she took on the roles of assistant, collaborator, model, and lover. As the art critic Mathias Morhardt explained at the time, “He consults her on everything.” In the meantime, Claudel produced and exhibited her own artworks. But her active participation in Rodin’s studio reduced her creative time and fueled criticism of her sculpture as derivative of his.

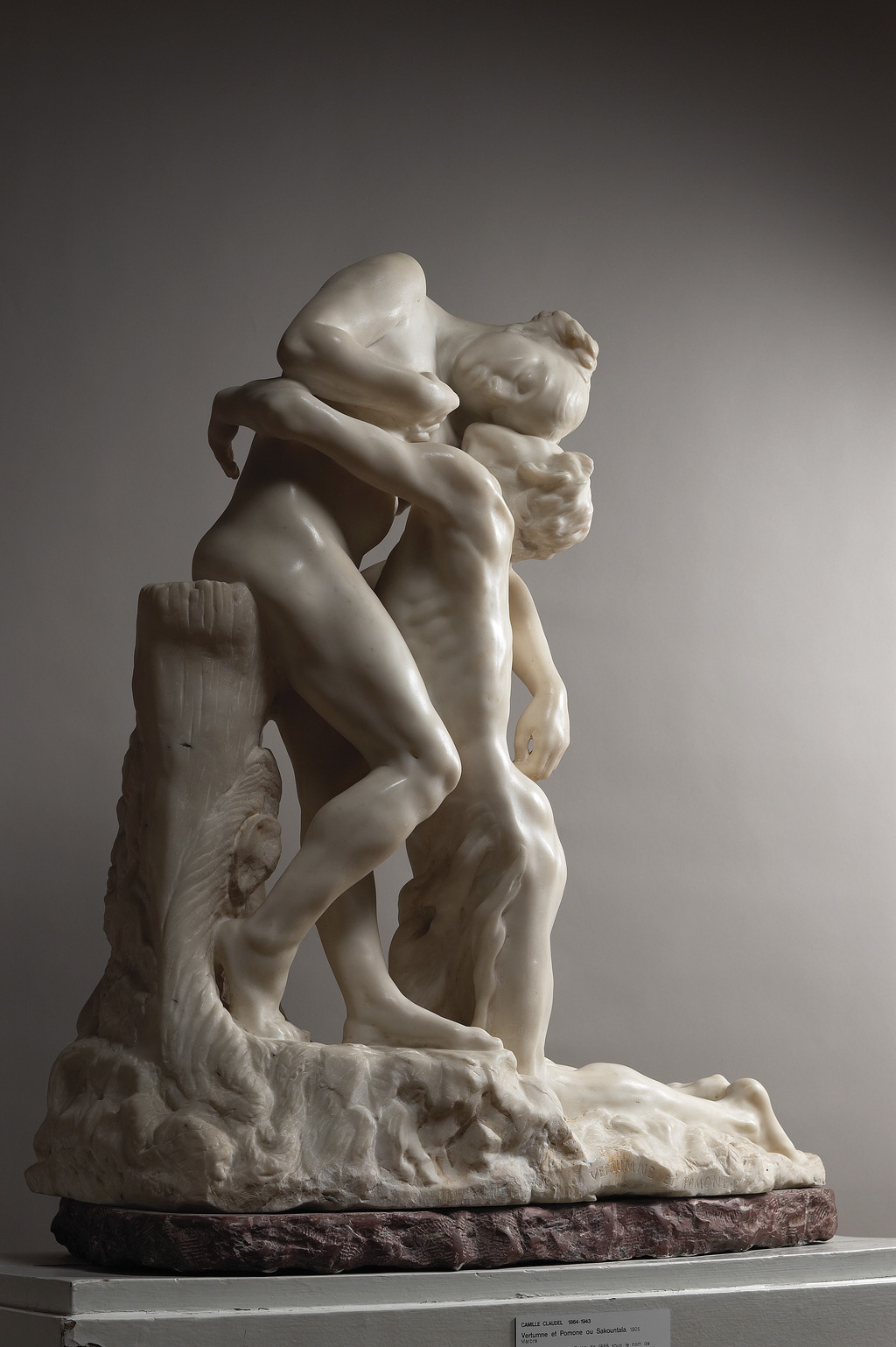

Tales of Passion

Claudel’s first major success was the large plaster group Sakuntala, which earned an honorable mention and glowing reviews when exhibited in Paris in 1888. The artist was unsuccessful, however, in securing a commission from the French government for a marble version of the group. The depiction of two lovers embracing was inspired by a Sanskrit play by the fifth-century Indian writer Kālidāsa, in which King Dushyanta loses his memory of his beloved Sakuntala. Claudel captured the scene of the lovers’ reunion, with the king falling at Sakuntala’s feet. In the early 1900s, Claudel reworked her composition, presenting it with different titles. The marble Vertumnus and Pomona refers to a Roman mythological tale and was completed in 1905 for her patron Countess de Maigret. When art dealer Eugène Blot produced it in bronze, the group was retitled The Abandonment. The French state acquired a cast of it in 1907.

The Waltz: A Sensuous Dance

Claudel’s Waltz is a daring, sensuous depiction of two lovers surrendering to a dance in a dynamic whirlwind. After a state-appointed art inspector rejected her initial composition, in which both figures were completely nude, she reworked the group, adding complex draperies, or “veils.” Although the new composition received critical acclaim when exhibited in plaster in 1893, the French government refused to commission it in marble. This version is known today thanks to a single, exceptional bronze cast. Building on collectors’ interest in the composition, Claudel produced a number of variations in tinted plaster, bronze, and even stoneware. In the later versions she reduced the drapery, especially around the female dancer, and modified the base mound. Shown in Belgium in 1894, in the United States the next year, and in Italy in 1911, The Waltz was one of the artist’s most frequently exhibited works outside France.

The Age of Maturity

Claudel created The Age of Maturity, one of her most ambitious sculptures, from 1890 to 1899. At once universal and deeply personal, it depicts Old Age leading Middle Age inexorably forward, beyond Youth’s grasp. Some viewers at the time may have associated the man with Rodin, the elderly woman with his long-term partner Rose Beuret, and the kneeling girl with Claudel, his lover. Decades later, Paul Claudel identified the young figure as his sister. The plaster model (now lost) was a success when it was first exhibited in 1899, prompting one critic to declare, “We can no longer call Mademoiselle Claudel a student of Rodin; she is a rival.” It is a mystery why the French state canceled its order for a bronze version of the group, but fortunately Claudel secured a commission from Captain Louis Tissier, a loyal admirer of her work.

The Little Lady

Claudel’s Little Lady portrays a wide-eyed girl staring confidently and curiously upward. The artist / the sculptor began the composition in 1892 during an extended stay at Château de l’Islette in France’s Loire Valley. Her model was six-year-old Marguerite Boyer, granddaughter of the estate’s owner. The sculpture proved a success, admired for its intense radiance and lively expression, and from 1894 on, Claudel produced it in plaster, bronze, and marble. The artist used her masterful carving skills to differentiate four marble commissions, two of which are in this exhibition. For one, now too fragile to travel, she sculpted an intricate hairstyle and partially hollowed out the marble, giving the child’s skin a translucent appearance. Such talent in execution, much praised by critics, distinguished Claudel from her colleagues, who typically entrusted the complex and time-consuming operation of carving marble to specialists.

Sketches from Life

In 1893, after concluding her personal and professional association with Rodin, Claudel isolated herself in her Paris studio. Stung by the continued comparison of her sculptures with Rodin’s, she was determined to forge a new style. She embarked on a series of compositions inspired by everyday life: scenes of women talking together, bathing in the ocean, or sitting alone before a fireplace. “You see,” she explained in a letter to her brother, “it is no longer anything like Rodin.” Departing from dramatic allegories and ancient sources of inspiration, Claudel’s sketches from life—miniature in scale and often employing novel materials—focused on the intimacy, poetry, and humanity of lived experience. “By taking the ordinary parts of life and instilling them with art and plasticity,” exclaimed the art critic Mathias Morhardt in 1898, “Mademoiselle Claudel has created a new art.”

The Last Decade

On December 1, 1901, the writer Maurice Pottecher sent art critic Gustave Geffroy a worrisome letter: “I saw Mademoiselle Claudel yesterday….She is exhausted to the point of despair. She wants to abandon her art, and she has already broken some of her molds. Her stormy and somewhat bizarre nature certainly explains in part the solitude, abandon, and near financial distress to which she has been reduced after having known all the promises of great success.” This account alludes to Claudel’s ongoing financial problems and foreshadows the decline of her mental and physical health in the last decade of her career—before her family confined her to a psychiatric hospital. Despite such challenges, she continued to create compelling works, receive important commissions, and participate in exhibitions. As she endeavored to stay afloat, several loyal supporters provided ongoing encouragement.

Claudel’s Legacy

On March 10, 1913, Claudel’s family committed her to a psychiatric hospital. Diagnosed with systematized delusion of persecution, she remained institutionalized, refusing to sculpt and showing symptoms of paranoia, until her death in 1943. A decade later the artist’s legacy began to emerge from obscurity. In 1951 the Musée Rodin in Paris organized the first Claudel retrospective. In the 1980s her life and artistic contribution became the subject of numerous books, exhibitions, and films, drawing wider public attention. In 2017 the Musée Camille Claudel was established in her former family home in Nogent-sur-Seine. Today, many French museums showcase her work and celebrate her as a trailblazing sculptor. The artist’s first retrospective in the United States was held in 1988 at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. In all, US public institutions hold fewer than ten of her sculptures, including the two recent acquisitions by the Art Institute of Chicago and the J. Paul Getty Museum presented in this exhibition.