|

|

|

Boussod, Valadon & Co. stock book, about 1900

|

|

|

|

|

|

The business of art is conducted much like any other commercial venture in which something is bought, sold, or traded, and yet a work of art is not a commodity in the ordinary sense. Its value can fluctuate radically in an instant, depending on the influence of collectors, dealers, curators, critics, or connoisseurs. Their assessments of historic, intellectual, and aesthetic values affect a work's monetary value in the marketplace.

The materials in this exhibition document past business activity in the art market. Recognizing their tremendous potential as research tools for the study of provenance (a work of art's history of ownership), and the history of aesthetics, taste, patronage, and collecting, the Getty Research Institute acquires the records of various players in the art market.

|

|

|

The role of the dealer, as middleman between artist and collector, has evolved into that of an influential art-world figure who can affect, and in some ways control, private and public perceptions of the history of art.

The stock book seen above came from the firm Boussod, Valadon & Co., an art gallery that successfully marketed the work of French academic and impressionist painters to an international clientele of collectors.

|

|

|

|

Taxes and Art, 1961

Spencer A. Samuels

|

|

|

In the late 1950s, dealer Spencer Samuels attempted to change the marketing approach of the New York firm French & Company, with a decided emphasis on art purchase as an investment opportunity. In 1959 he began publishing a newsletter for businessmen, Currency of Art, which presented the acquisition of art as a classic investment.

Taxes and Art took this marketing approach to a more refined level. The publication gave detailed instructions on how to purchase magnificent works of art while deducting great amounts from one's taxes. These instructions were accompanied by glossy illustrations of works of art, all owned by French & Company.

|

|

|

|

|

Countess of Verrue collection sale catalogue, about 1777

|

|

|

|

|

|

Art collecting by individuals emerged in the 16th century, following the tradition of collecting natural history specimens. A collector may be motivated to acquire works of art for a variety of reasons: aesthetic preferences, investment, speculation, scholarly study, or even as a social outlet.

The Countess of Verrue amassed one of the largest and best-known private collections of the 18th century. It consisted of pioneering purchases of Spanish 17th-century genre pieces, Dutch and Flemish cabinet pictures, and commissioned works of contemporary French artists. This rare sale catalog of her collection is unique in that it only exists in handwritten manuscript form, of which there are several versions. This version notes later owners of some works of art, indicating that it was written about 40 years after the sale. The practice of providing provenance of works of art seems to have derived from sales such as this.

The first entry on this page of the sale cataloge, no. 87, lists Rembrandt's painting The Abduction of Europa, now in the Getty Museum's collection. The first entry on this page of the sale cataloge, no. 87, lists Rembrandt's painting The Abduction of Europa, now in the Getty Museum's collection.

|

|

|

|

Letter from André Lhote to Gabriel Frizeau, November 11, 1908

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1908, Bordeaux collector Gabriel Frizeau sponsored artist André Lhote's trip to Paris, employing him as an agent to provide information on the Paris art scene. Lhote sent Frizeau elaborate descriptions and sketches of paintings by Paul Gauguin currently for sale at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard. Frizeau had already purchased Gauguin's Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? from Vollard in 1901.

In this letter, Lhote particularly recommends two pictures: one of Tahiti, and the other of a "Christ who looks like Gauguin himself." Lhote also recommends the works of an artist "who is not known at all in the art market—Emile Bernard—whose paintings are filled with their own style and personality."

|

|

|

|

|

Letter from Antonio Canova to Napoleon Bonaparte, October 18, 1810

|

|

|

|

Artists also participate in the art market, sometimes acting as agents, dealers, critics, and collectors.

The renowned Italian sculptor Antonio Canova was a clever diplomat able to undertake major commissions for patrons who were affirmed enemies, while remaining loyal to Italy. While spending some weeks at the French court to execute a portrait of Napoleon's new empress, Marie-Louise, Canova seized the opportunity to speak with the emperor about politics, history, and the arts.

In this letter, Canova reports his progress on his portrait of the empress. His conversations with Napoleon at this time allowed Canova to secure financial support for the Italian academies and monuments. After the emperor's fall in 1815, Canova successfully worked to recover works of art that had been removed from Italy by Napoleon.

|

|

|

|

Letter from Paul Gauguin to Camille Pissarro, July 29, 1879

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1879, at the age of 31, Paul Gauguin was earning an impressive 30,000 francs annually (over $100,000 today) as a stockbroker in Paris. He spent his weekends studying with Pissarro and, at the time of this letter, had just purchased three of his paintings. Gauguin acted as an agent for his teacher, persuading his colleagues to invest in Pissarro's paintings.

In this letter to Pissarro, Gauguin reports that he has been commissioned to purchase two paintings for an employee at the stock exchange and "naturally I am having him take some Pissarros...." In April, Pissarro sponsored Gauguin's participation in the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition. After the stock market crash of 1882, Gauguin lost his bank job and devoted himself entirely to his career as an artist.

|

|

|

|

|

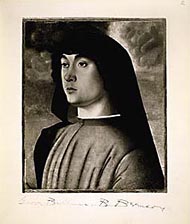

Bernard Berenson Attestation Album, about 1908–1937

|

|

|

|

The scholar can exert considerable influence on the art market. As an advisor to museums, individual collectors, auction houses, and other agencies, they authenticate works of art and can assess and set aesthetic and market valuations.

The art historian Bernard Berenson helped create a market for early Italian Renaissance art through his business relationship with London dealer Joseph Duveen. Duveen regularly sent photographs of works to Berenson, who noted his attribution on the photos and signed them. In this case, Berenson assigned the painting to the Venetian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini. Duveen kept these "attestation" photographs, showing them to clients as certificates of authenticity. If Duveen sold the work, Berenson would receive 25% of the sale price.

|

|

|

|

Plotted "Success Points" for the Work of Andy Warhol, late 1960s

Willi Bongard

|

|

|

Fascinated by the high prices achieved by contemporary (postwar) art, the German art critic Willi Bongard developed a system, known as the Kunstkompass, for ranking artists based on indicators of fame. Using data gathered from museums, commercial art galleries, and art journal reviews, Bongard calculated the success of an artist from year to year and compared it to gallery prices, thus determining the artist's investment potential.

In the graph shown here, Bongard charts the growth in "success points" of Pop artist Andy Warhol's work from 1970 to 1979 based on his Kunstkompass calculations (black line), as well as his advancement in the overall ranking in the Kunstkompass (red line). Bongard's system of analysis is widely used in Germany today as a guide for investors speculating on contemporary art.

|

|