Explore the Exhibition

Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment

By Anne-Lise Desmas and Édouard Kopp

ONE OF THE MOST FASCINATING ARTISTS of eighteenth-century Europe, Edme Bouchardon (1698–1762) was instrumental in the transition from the decorative exuberance of the Rococo style to the spare linearity of the Neoclassical. A prominent member of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris, he was much celebrated in his time as both a sculptor and a draftsman. In France, as official sculptor to the king and also draftsman to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres, he created some of the best-known images of the age of Louis XV (reigned 1715–1774), from the small and private to the monumental and public. The result of his prolific imagination and constant quest for perfection, his works were praised and sought after by the most discriminating art collectors of Europe.

This major international loan exhibition, developed in partnership with the Musée du Louvre, is a testament to the remarkable variety of his oeuvre and to his masterful techniques in different media. Organized chronologically, the show explores key themes of Bouchardon’s art through selected masterpieces that highlight his strong commitment to life drawing, his investigation of the relationship between drawing and sculpture, and his passion for ancient art.

Download the exhibition object checklist

Bouchardon in Rome

The varied repertoire of styles that Bouchardon studied in Rome shaped his production as a sculptor and draftsman.

A Classical Education

After receiving first prize from the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris, Edme Bouchardon was granted a sojourn at the French Academy in Rome. He arrived there early in autumn 1723, when he was twenty-five years of age, and departed late in the summer of 1732. The French Academy, which was founded under Louis XIV in 1666, required young artists to learn by copying classical art and the great masters, a method of education that had been practiced since the Renaissance.

A great number of Bouchardon’s drawn copies have survived; they include complete compositions as well as details, nearly always executed in red chalk, his favorite medium. In addition to ancient sculpture and the great masters of the Renaissance, he copied works by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and other Baroque artists.

From 1726 until 1730, Bouchardon carved a marble copy of a classical statue, a mandatory exercise for the Academy’s sculptors. He chose as his model the Barberini Faun. The rich and varied repertoire of forms and styles that Bouchardon studied in Rome shaped his production as a sculptor and draftsman.

Early Patronage

During his nine years in Rome (1723–32), Bouchardon not only refined his

artistic education by copying the ancients and the masters but also made a

brilliant start on his career. French ambassador Cardinal de Polignac introduced Bouchardon to influential cardinals in the papal court and to scholars, artists, collectors, antiquarians, and aristocrats in Rome.

Starting in 1727 with the bust of Baron Philipp von Stosch, Bouchardon carved several other portraits in a classicizing style to suit the demands of certain patrons, mostly British aristocrats. The appropriation of classical art in these works represented a novelty in portraiture at the time. Bouchardon also excelled in sculpting busts in a Baroque style that owed much to Bernini, evident in the portrait of Pope Clement XII.

Motivated by a strong creative impulse, the young artist worked on models

for many projects in Rome, including Pope Clement XI’s tomb, the Corsini

Chapel, and the Trevi Fountain, but none of his designs were executed. In 1732 Bouchardon was called back to France by a royal administration eager to use his talents in Paris and Versailles.

Bouchardon’s Notebooks

In addition to more than two hundred drawn copies conserved in the Louvre and other museums, two of Bouchardon’s notebooks have been preserved. Entitled Vade Mecum (Latin for “come with me”), these small-format, lightweight notebooks were easily carried in Bouchardon’s pocket while he walked around Rome, allowing him to remember artworks he particularly liked by making quick sketches of them in red chalk.

Fountains

Bouchardon was called back to France by a royal administration eager to use his talents in Paris and Versailles.

Bouchardon particularly enjoyed designing fountains because he could combine sculpture, architecture, decoration, and water features in a single work of art. He created one of his first designs in Rome in the early 1730s, when he entered the competition for the Trevi fountain.

Although Bouchardon designed about thirty fountains—some for urban settings but most for gardens or parks in Rome and Paris—only two of his ideas were executed. In 1739 he completed sculptures in lead for the Neptune Fountain at Versailles. His Proteus Accompanied by Dolphins and Seals is among the fountain’s three most significant sculptural groups, and his two Geniuses Riding Sea Dragons adorn the ramps on the either side of the basin.

Bouchardon’s most important commission was the Grenelle Fountain (1739–

45) in Paris. His work in this field was so innovative that the 1747 edition of La théorie et la pratique du jardinage, an influential book on gardening by Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville, included several illustrations of fountains after Bouchardon’s drawings.

Grenelle Fountain

The rapid growth of the Faubourg Saint-Germain district made better water distribution a necessity, and in 1739 the Paris city council purchased a property on the Rue de Grenelle for a public fountain. Bouchardon received the commission for the design and was responsible for all aspects of its decoration. It was completed in 1745.

The fountain’s facade is formed by a central section flanked by two concave sections, or “wings.” In front of the central pediment supported by two pairs of columns is the primary figural group in marble: the city of Paris, personified as a seated woman, accompanied by two reclining figures representing the Seine and the Marne rivers. At street level, water spouts from four grotesque bronze heads. On the flanking sections, statues and allegorical reliefs, all in stone, evoke the four seasons.

The Grenelle Fountain was a major monument in the development of Paris as a metropolis. The design—a revival of the classical tradition—aroused passionate debate among contemporaries, while the sculptural decoration was highly praised for its depiction of nature.

Religious and Funerary Art

Bouchardon was introduced to religious art by his father, an architect and sculptor who produced altarpieces and church furnishings.

Bouchardon was introduced to religious art at a very young age by his father, Jean-Baptiste, an architect and sculptor who produced altarpieces and church furnishings in Champagne and Burgundy. His earliest known work, a stone relief for a church, represented the martyrdom of Saint Stephen.

In Rome, Bouchardon copied many religious subjects and tomb figures. Before leaving Italy, he created a model for the statue of Justice for the Lateran’s Corsini Chapel, which he never executed at full scale.

In France, his most important religious commissions were the choir decoration of the Saint-Sulpice church in Paris and a bronze relief for the Chapel of Versailles.

Throughout his career, Bouchardon designed many compositions for funerary monuments, which are known exclusively by his drawings. Unfortunately, prestigious commissions, such as the tombs for Pope Clement XI and Cardinal de Fleury were abandoned, and the few tombs he did execute are no longer extant. Bouchardon's religious and funerary art is very inventive, and it succeeds in depicting deep and complex feeling with great sincerity.

Cupid

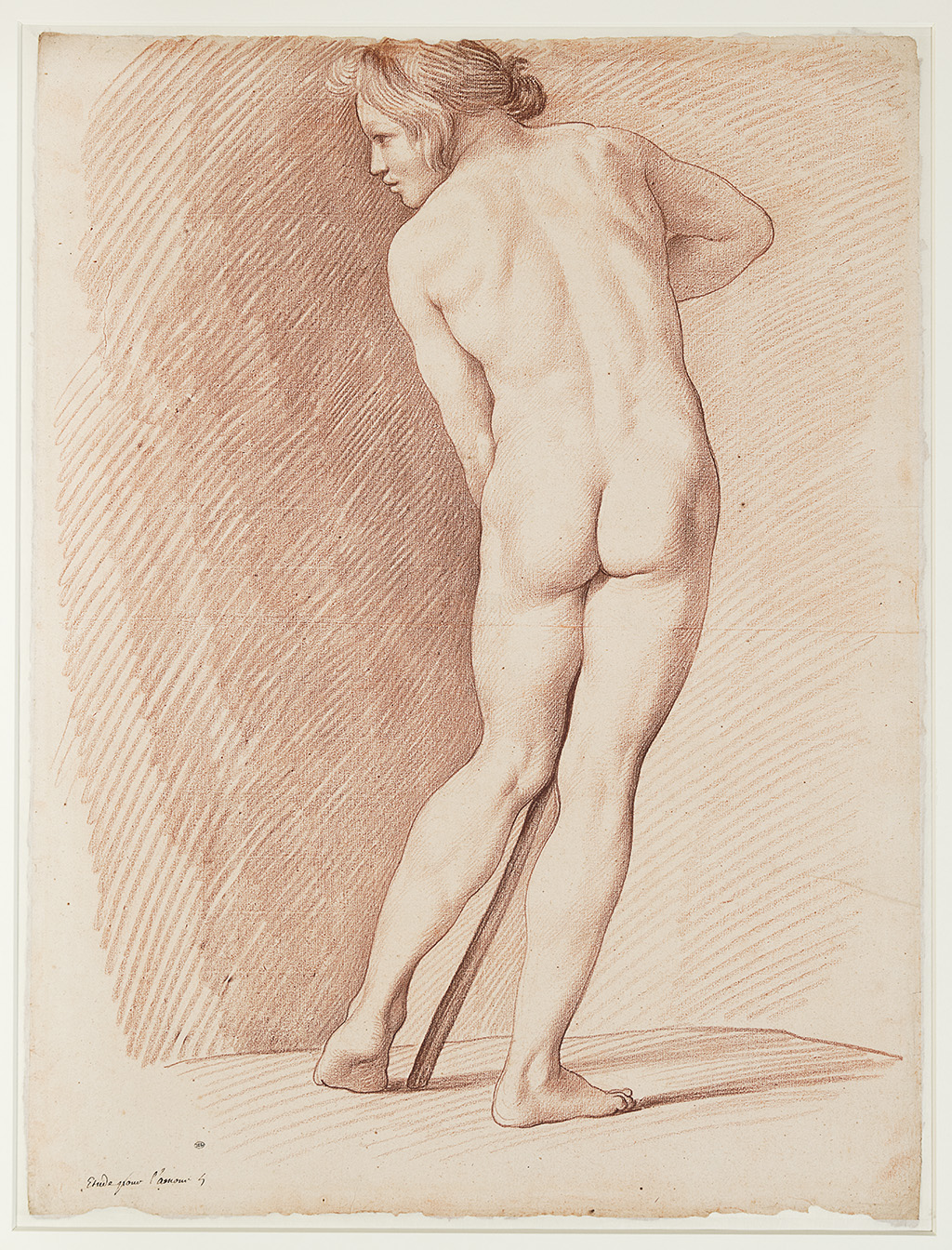

The embodiment of Bouchardon’s aesthetic, Cupid combines ancient art's simplicity of forms with a faithful attention to nature.

Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club represented a major royal

commission for Bouchardon, which occupied him between 1745 and 1750.

The statue was installed at Versailles in 1750, in the War Salon, the room at the north end of the Hall of Mirrors. Two years later it was moved to the Hercules Salon, next to the royal chapel. The statue aroused much criticism. Several people, including the philosopher Voltaire, considered the subject to be enigmatic and unpleasant, turning the god of love into a “carpenter.” The courtiers, especially women, thought Bouchardon’s depiction of the youth’s body was overly realistic, reducing Cupid to a common street porter. By 1754 Cupid had been sent to the castle of Choisy to be displayed in the orangery. This was near a small château used as a retreat by Louis XV and his mistress Madame de Pompadour, making it an appropriate site for the Cupid.

Art critics and artists, however, recognized the novelty of this masterpiece. The perfect embodiment of Bouchardon’s aesthetic, it combines the simplicity of forms of ancient art with a faithful attention to nature.

Drawing Medals, Engraved Gems

Associated with antiquity, medals and engraved gems enabled an historically minded Bouchardon to connect with the classical world.

From 1737 until 1762, the year of his death, Bouchardon occupied the prestigious position of draftsman of the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles- Lettres. This royal institution, founded under Louis XIV, had the dual mandate of advancing knowledge about classical antiquity and history and providing inscriptions for the regime’s propaganda.

Bouchardon’s primary task was to draw designs for tokens and medals based on ideas developed by the academicians. Tokens were distributed annually to employees of the royal administrations, while medals commemorated major events of Louis XV’s reign, from 1715 to 1774. The obverse (front) of each token or medal usually contained a portrait of Louis XV; the reverse featured a composition comprising an image, a Latin motto, and a description of the event or subject being celebrated.

In addition to medals and tokens, Bouchardon was very involved with another type of small monument in low relief: engraved gemstones. Closely associated with antiquity, when it had flourished, this diminutive art form enabled a historically minded artist such as Bouchardon to connect with the classical world, which fascinated him.

Innovations in Graphic Arts

Bouchardon disseminated many of his works through prints, which helped establish his reputation as prolific draftsman.

Dating essentially from the 1730s and 1740s, the drawings and prints in this section attest to Bouchardon’s remarkable inventiveness in the graphic arts. His wide-ranging interests led him to depict allegory, myth and fable, ancient history, the decorative arts, caricature, and the animal world. While some drawings, such as the Cries of Paris, were meant to serve as models for prints, many others were intended as independent works.

Bouchardon’s belief in the relative autonomy of his practice as a draftsman was reflected in his decision to exhibit drawings unrelated to his sculpture at the Paris Salon exhibitions between 1737 and 1746. This was highly unusual at the time, certainly for a sculptor, who would have been expected to exhibit only three-dimensional objects.

Bouchardon disseminated many of his innovative works through his collaboration with the comte de Caylus, an amateur printmaker, and Étienne Fessard, a professional engraver, which helped establish his reputation as prolific draftsman.

Some of his compositions reflect his desire to create drawings in the grand manner of historical painting, although using only red chalk. His inventive genius was particularly stimulated by fables and myths.

Louis XIV Equestrian Monument

Louis XV’s right hand is the only surviving fragment of the seventeen-foot-tall statue destroyed during the Revolution.

In 1748 the aldermen of Paris resolved to erect a statue in honor of Louis XV. Bouchardon’s last major commission, it represented the king on horseback, wearing classical costume and crowned with laurel leaves. In his right hand he held the baton of command, resting on his thigh. When finished, the monument— about thirty-nine feet tall, including the pedestal—was to be installed on the Place Louis XV (present-day Place de la Concorde).

The preparatory work took a long time, and in fact occupied the sculptor until his death. After producing a great number of drawings, Bouchardon completed a large-scale plaster model in January 1757. The casting in bronze took place on May 5, 1758; however, a setback with the casting, coupled with Bouchardon’s meticulousness, delayed the sculpture for five years while it was repaired and refined. The statue was installed on a temporary pedestal in 1763, several months after the artist’s death. The pedestal was completed nine years later with the addition of the bronze decoration of four Virtues and two reliefs by sculptor Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714–1785). The seventeen-foot-tall statue was destroyed in 1792 during the Revolution. Louis XV’s right hand is the only surviving fragment of the original.