Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems

In Dialogue

Dawoud Bey (American, born 1953) creates photographs that focus on individuals, communities, and important but often overlooked American histories. His carefully composed images convey the dignity and rich inner lives of his subjects. Carrie Mae Weems (American, born 1953) first gained recognition in the 1980s for exploring identity, gender, race, power, and history, themes that still fuel her art. Over her career, Weems has turned increasingly to staged photography and the use of text to heighten the emotional intensity of her work.

Early Works

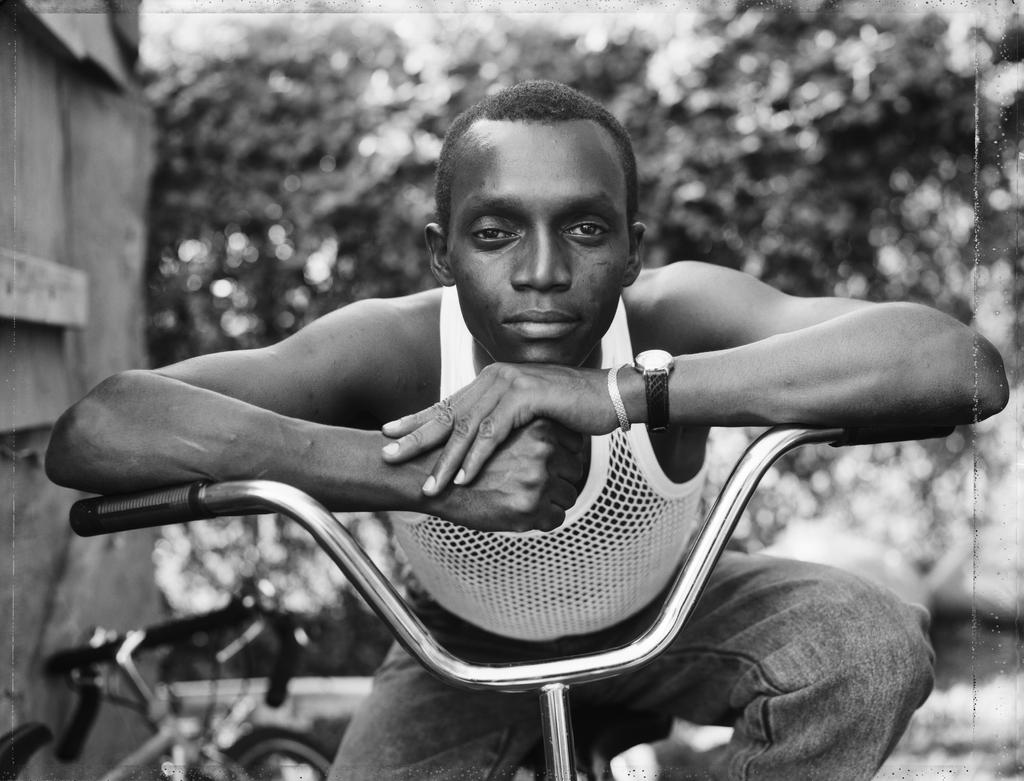

When Bey and Weems met in 1976, both were committed to using photography to record their own presence in the world and create sympathetic representations of Black life of the sort rarely seen at the time. In their pictures from the 1970s and 1980s, each documented the hustle and bustle of everyday experience as well as moments of quiet reflection. As young artists, they experimented with a variety of photographic and printing styles to shape the impact of their photographs.

Broadening the Scope

By the late 1980s, Bey and Weems had both moved beyond candid pictures of everyday life and had begun making works that were larger in scale and more planned than spontaneous. Bey’s portraiture evolved from street-based glimpses of the world made with a handheld camera to portraits that are formal but intimate, in which his subjects appear at ease and engage directly with his lens. With Kitchen Table Series, Weems transitioned from representing real people in their natural environments to creating a staged photo essay. For each artist, the techniques developed in this period became the foundation for future projects.

Resurrecting Black Histories

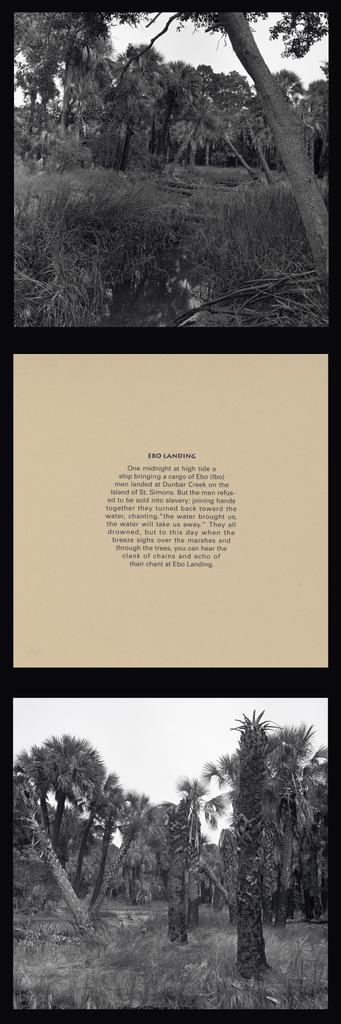

Bey and Weems brought attention to American landscapes and experiences largely absent or simplified in the nation’s historical record, reframing United States history by attending to Black lives and losses. Though each addresses the nineteenth century and its legacies, they do so in distinctive ways. Bey’s carefully composed landscapes evoke the experience of fleeing along the Underground Railroad, the clandestine network that helped enslaved people escape the South. Weems, by incorporating texts that intermingle past and present, referenced African Americans whose lives and stories have been co-opted or lost.

Memorial and Requiem

In the two series in this section—Bey’s The Birmingham Project and Weems’ Constructing History, A Requiem to Mark the Moment—they referenced traumatic twentieth-century events. They worked with community partners on these projects, staging people in scenes meant to reinvigorate discussion of America’s legacy of racial violence.

Each photographer also created a related work of video art, bringing their own sensibility—Bey’s searching, intimate gaze, Weems’s choreographed social commentary—to the moving image, using sequencing and sound to deepen engagement with American history. The videos are on view in the exhibition.

Revelations in the Landscape

In the 2000s both Bey and Weems contemplated the built environments we live in and how those spaces affect our perceptions of the world and ourselves. Bey returned to the Harlem neighborhoods he had photographed in the late 1970s, tracking the changes wrought by gentrification. Weems photographed imposing sites in Rome, inserting herself into historical places imbued with power. Both series reveal the economic and institutional forces that undergird daily life.