|

|

The Florentine Codex No source is more valuable for understanding Aztec civilization than the Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España (General History of the Things of New Spain), familiarly known as the Florentine Codex after its location in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence. For this exhibition, the Florentine Codex returns to the New World for the first time in over four centuries. The codex was compiled by Franciscan friar and pioneer ethnographer Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590), who taught Latin, rhetoric, and theology to indigenous youths training for the priesthood at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, the first university in the Americas. Working with students and native elders, he directed a 30-year project to describe the Aztecs in Spanish as well as Nahuatl, with the aim of creating "a treasure," in Sahagún's words, "for knowing many things worthy of being known." His ethnographic enterprise represents an extraordinary effort to spread the Christian faith through cultural understanding rather than coercion. The codex is illustrated with over 2,400 images describing Aztec religion, rituals, agriculture, commerce, and crafts. Six of these are shown below. |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

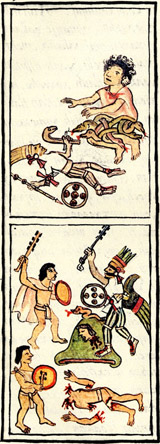

The Birth of Huitzilopochtli When the mother goddess Coatlicue (Serpent Skirt) was magically impregnated, her daughter Coyolxauhqui led 400 brothers against her. The god Huitzilopochtli sprang from Coatlicue's womb fully armed, defeated his siblings, and decapitated Coyolxauhqui, whose dismembered body fell to the base of Coatepec (Serpent Mountain). |

|

|

|

The Festival of Toxcatl Every spring a war captive of superior physical beauty was chosen to impersonate the god Tezcatlipoca (Smoking Mirror). Worshipped like a deity, the captive was adorned in precious clothing and given wives and servants in a yearlong rite that culminated in his sacrifice to the god. |

|

|

|

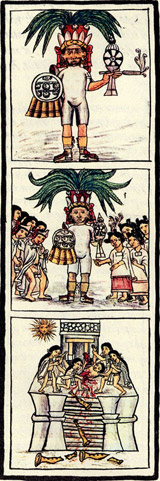

The Legend of the Cihuateteo The angry Cihuateteo, spirits of women who had died in childbirth, were believed to descend from the night sky on the day 1 Eagle to harm or kidnap children. Communities made offerings in their homes, at temples, and at crossroads to pacify the spiteful spirits. |

|

|

|

|

The Art of Featherwork Featherworking was an esteemed trade plied by elite families. Master amanteca (feather artisans) used exotic quetzal and scarlet-macaw feathers imported from tropical southern regions to adorn shields and banners. Feather headdresses and back ornaments were status symbols worn by rulers in ceremonies. |

|

|

|

The Art of Goldwork Intricate jewelry and vessels reserved for the Aztec nobility were cast in gold using clay molds covered in copal-hardened beeswax. Objects created in this sophisticated lost-wax technique captured the attention of the Spanish conquistadors who sought the legendary gold treasure of Motecuhzoma II. |

|

|

|

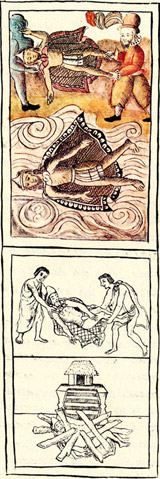

The Death of Motecuhzoma II The final book of the codex illustrates the death of Motecuhzoma II on June 30, 1520. The degree of Spanish responsibility is ambiguous. According to the Nahuatl text, after the Spaniards had thrown the emperor's corpse into a canal, local residents dishonorably burned his remains over a woodpile. |

|

|

|||||||||||