Nineteenth-Century Photography Now

Introduction

The earliest photographs—often associated with small, faded, sepia-toned images—may seem to belong to a bygone era, but many of the conventions established during photography’s earliest years persist today. Organized around five themes dating back to the medium’s beginnings, this exhibition explores nineteenth-century photographs through the work of twenty-one contemporary artists. Reflecting the inventiveness of early practitioners as well as the more disturbing historical aspects of their era, these interchanges between the first decades of the medium and the most recent invite us to reimagine nineteenth-century photography while exploring its complexities.

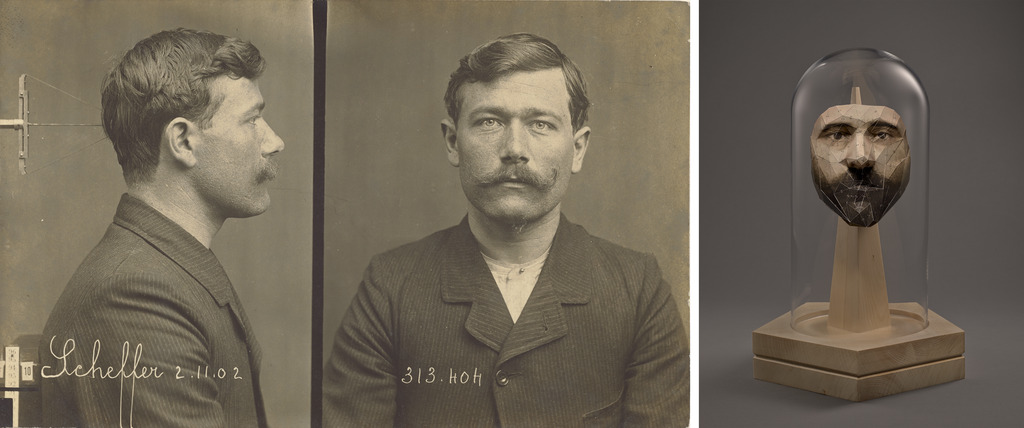

Identity

As is still the case today, the most popular subjects for the camera in the nineteenth century were people. Early commercial portrait photographers set up studios and established standards for posing and props, serving clients who eagerly shared these prized images with family and friends. Other portraits of the time, however, such as the mug shot and studies of female “hysterics,” reinforced questionable forms of objectification. Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Myra Greene respond to the complex history of photographic portraiture. Fiona Tan, Laura Larson, and Stéphanie Solinas investigate the nineteenth century pseudosciences that relied on the perceived accuracy of the new medium.

Time

Photography and time have been inextricably linked ever since early inventors such as William Henry Fox Talbot struggled to permanently fix a fleeting moment on a sheet of paper. The development of the camera coincided with new discoveries about how we perceive an instant in time or an object in motion, and people praised photography for its ability to “stop time” and record what the unaided eye could not see. Lisa Oppenheim and Liz Deschenes respond to nineteenth century photographers’ technical innovations and the ways in which the medium affects our perception of time. Phil Chang and Hiroshi Sugimoto address the fate of photographs across minutes or even centuries.

Spirit

The genre of spirit photography—which used photographic tricks to insert ghostly figures among the living—emerged during the nineteenth century from the Victorian obsession with death, séances, and mediums in Europe and North America and from the losses of the Civil War in the United States. Photographers exploited the ability to manipulate photographic images, employing multiple exposures and staged photography to create otherworldly scenes or to summon loved ones back from the dead. Khadija Saye and Lieko Shiga respond to the possibilities that spirit photography offers in rendering the unseen.

![Mrs. Swan, 1869–78, William H. Mumler. Albumen silver print. Getty Museum; Nak Bejjen [Cow’s Horn], 2017-18, from the series in this space we breathe, Khadija Saye. Silkscreen print. Getty Museum, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council. © Estate of Khadija Saye](/art/exhibitions/19_century_now/images/2_7_GMR_2038_012.jpg)

Landscape

Nineteenth-century photographers went to great lengths to make images of remote landscapes, which required traveling with large format cameras, glass plates, and chemicals. Ideological forces drove many of these journeys, with the ultimate goal of imperial expansion through industrial development and war. Government sponsored surveys and expeditionary programs employed the camera to justify the expansion and to record the resulting military conflicts. Mark Ruwedel, Michelle Stuart, and An-My Lê re-envision some of these same historical landscapes and offer up new ones that bring the past closer to our present.

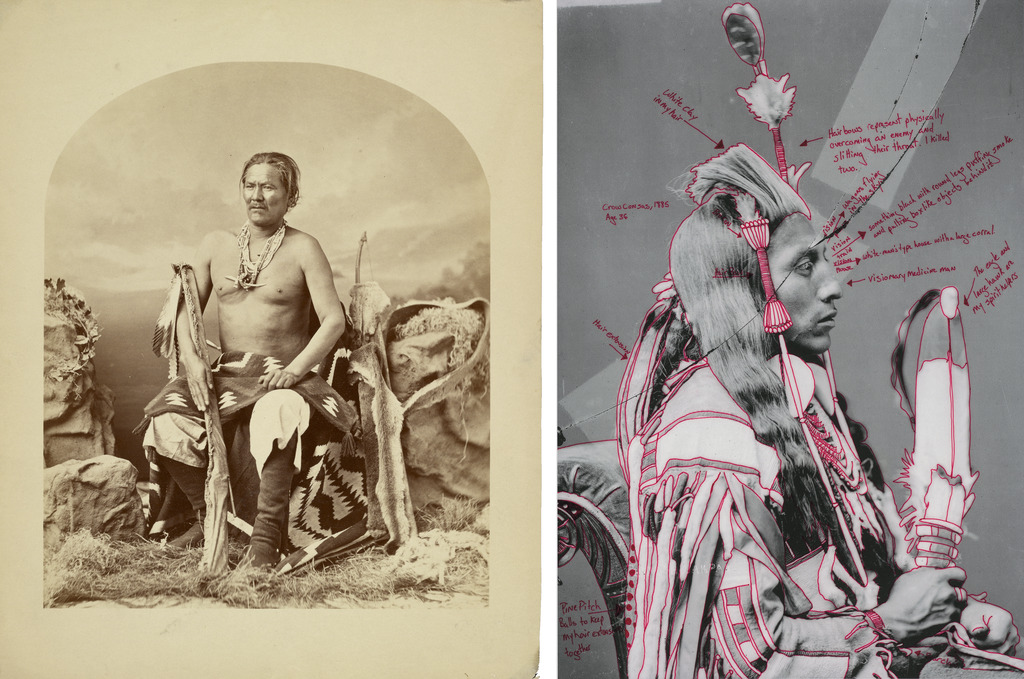

Circulation

By the middle of the nineteenth century, thousands of photographs were in circulation worldwide, the result of photographers’ ability to reproduce the same image multiple times. Pictures of historical events, tourist destinations, and anthropological expeditions made the world seem more accessible, but with time and distance, they became disconnected from their original contexts. Many eventually ended up in archives (including at Getty). Early photographs appear next to projects that make these historical absences present. Wendy Red Star, Stephanie Syjuco, Ken Gonzales-Day, and Andrea Chung recover what has been lost, calling out the residual effects of the nineteenth-century photograph on our present knowledge of global cultures and histories.