Reconstructing Nikolaus Pevsner's Townscape

An Interview with Mathew Aitchison

In the mid-1940s Nikolaus Pevsner (1902–1983) fully planned, wrote, and almost completed a seminal work on town planning and the picturesque, or Townscape. In 1984 the Getty Research Institute (GRI) acquired this manuscript as part of the Nikolaus Pevsner papers, an archive that includes 143 boxes of typed and handwritten notes, clippings, photographs, books, lecture notes, and manuscripts.

It was nearly 15 years before anyone realized what the archive contained—and not until 2010 that the manuscript finally appeared in print as Visual Planning and the Picturesque.

In this four-part interview, GRI editor John Hicks talks with scholar Mathew Aitchison about how he reconstructed the manuscript, the context in which it was written, Pevsner's role as a critic, and the future of visual planning and Townscape.

It was nearly 15 years before anyone realized what the archive contained—and not until 2010 that the manuscript finally appeared in print as Visual Planning and the Picturesque.

In this four-part interview, GRI editor John Hicks talks with scholar Mathew Aitchison about how he reconstructed the manuscript, the context in which it was written, Pevsner's role as a critic, and the future of visual planning and Townscape.

1. Unearthing the Manuscript

How did Pevsner's manuscript come to your attention?

While researching context in architecture and urban design, I needed to examine Townscape. My doctoral supervisor, John Macarthur, suggested I look at Nikolaus Pevsner's work on the picturesque. When John was a student at Cambridge, he was taught by Joseph Rykwert. Rykwert had told him that it was Pevsner who was behind many ideas from the Townscape movement.

|

|

So I read anything I could get, including the Reith Lectures that Pevsner did on the British Radio in the early 1950s. These lectures were published as The Englishness of English Art in 1956. In that book he included a footnote: "I am working on the book on Visual Planning and the Picturesque."

My eyes lit up. One of the biggest art historians is talking about a book he was writing on a movement that I'm now researching? And nobody knows where the manuscript is. When you add Rykwert's account that Pevsner was an unseen hand in Townscape, this was very exciting. I had to find the manuscript.

I did an enormous amount of research, which pointed to the existence of this manuscript. Around the same time, a colleague handed me a paper by Edem Erten, then a young PhD student, that said that Pevsner's archives were at the Getty Research Institute and the visual planning manuscript was there in box 25.

My eyes lit up. One of the biggest art historians is talking about a book he was writing on a movement that I'm now researching? And nobody knows where the manuscript is. When you add Rykwert's account that Pevsner was an unseen hand in Townscape, this was very exciting. I had to find the manuscript.

I did an enormous amount of research, which pointed to the existence of this manuscript. Around the same time, a colleague handed me a paper by Edem Erten, then a young PhD student, that said that Pevsner's archives were at the Getty Research Institute and the visual planning manuscript was there in box 25.

|

|

So I went to Los Angeles, saw the manuscript, and realized straightaway that one week wasn't enough time to transcribe it.

It wasn't clear what the manuscript was, or how significant it was. I told Wim de Wit, head of GRI Special Collections at that time, that if I could transcribe it, we could assess how important it was. But if it stayed in the box, who knows when someone would next look at it.

So, his staff copied the entire manuscript and the associated illustrations. Parts I and II were largely complete, whereas only notes existed for Part III. Then I went to work. The rough transcription was complete in early 2005 but far from ready for publication. It took four to five years' work, on and off, to complete the book.

It wasn't clear what the manuscript was, or how significant it was. I told Wim de Wit, head of GRI Special Collections at that time, that if I could transcribe it, we could assess how important it was. But if it stayed in the box, who knows when someone would next look at it.

So, his staff copied the entire manuscript and the associated illustrations. Parts I and II were largely complete, whereas only notes existed for Part III. Then I went to work. The rough transcription was complete in early 2005 but far from ready for publication. It took four to five years' work, on and off, to complete the book.

How did you decipher Pevsner's handwriting?

|

|

His handwriting is atrocious—minute and illegible. Originally I had about 50 blanks. It took two years to reduce those to six blanks. There are seven words that look exactly the same in his script: words like not, or, and, if. Obviously, they make a big difference!

Also, his vocabulary is quite rich for somebody who is not a native English speaker. It took three to four years to decipher "vermiculated" and "trellis of vitrified headers." But looking back, his handwriting is very beautiful.

Also, his vocabulary is quite rich for somebody who is not a native English speaker. It took three to four years to decipher "vermiculated" and "trellis of vitrified headers." But looking back, his handwriting is very beautiful.

What was it like to edit someone else's unfinished manuscript?

I suppose biographers have that same sense of working on a project that's not one's own. But you become so immersed in the material that you almost can write the voice of the person.

I speak German fluently and lived in Germany for 15 years. In many places, Pevsner used shorthand German notes that would have completely baffled anyone reading it. But I could understand his shorthand notes, because they were about things that a young German student would customarily write.

I speak German fluently and lived in Germany for 15 years. In many places, Pevsner used shorthand German notes that would have completely baffled anyone reading it. But I could understand his shorthand notes, because they were about things that a young German student would customarily write.

|

|

Also, my research on Pevsner and on others in the Townscape movement enabled me to triangulate what Pevsner was saying, what he had said elsewhere, and at which time; to set out a chronology of these works; and then to document the changes that his thinking underwent.

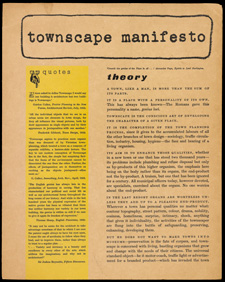

Also, Pevsner's style in Parts I and II of the manuscript was similar to what he used in his many Architectural Review articles on Townscape: what he called a florilegium, a series of quotes strung together with captions or titles. For him, this was a quick way to display a lot of historical material in a relatively informal manner.

So I used this style in Part III. But it's slightly ironic that Part III is finished in the style that he used to present other people's works from the 18th century. Then again, it is a strange situation to find yourself recreating somebody else's work.

Also, Pevsner's style in Parts I and II of the manuscript was similar to what he used in his many Architectural Review articles on Townscape: what he called a florilegium, a series of quotes strung together with captions or titles. For him, this was a quick way to display a lot of historical material in a relatively informal manner.

So I used this style in Part III. But it's slightly ironic that Part III is finished in the style that he used to present other people's works from the 18th century. Then again, it is a strange situation to find yourself recreating somebody else's work.

2. Urban Planning in Postwar England

Why does Pevsner's work warrant renewed attention?

The tides of taste in architectural scholarship, and in architecture and urban design, are strong and can be vicious. Towards the end of Pevsner's career, he was much vilified. Many people never got over the fact that Pevsner was a German researching a very, very British subject and pitching it in his own unique way.

But beyond that was his support for modernism in architecture. In the 1970s there was a backlash against modernism. So it seemed convenient to criticize Pevsner for proposing modern architecture full stop—because modern architecture was bad and passé and postmodern architecture was the best new thing.

But beyond that was his support for modernism in architecture. In the 1970s there was a backlash against modernism. So it seemed convenient to criticize Pevsner for proposing modern architecture full stop—because modern architecture was bad and passé and postmodern architecture was the best new thing.

|

|

Pevsner was also an advocate of modern urban design, which, for his critics, was even worse than modern architecture.

But if you fast-forward 20 years, people became interested in Pevsner again for the same reasons that they were not interested in him in the late 1970s.

That is, Townscape is a very modern movement. This is something that has fallen by the wayside. Most people think that Townscape was about making tasteful street furniture or lighting, seats, benches, and litterbins to match an urban design scenario. They absolutely do not think that it's about modern architecture adapted in a very free-form way to concrete problems of reconstruction.

Today's interest in Pevsner's work, in Townscape and visual planning—indeed, in the mid-century architectural and urban design milieu—has to do with the rekindled interest in modernism as something that is not inherently flawed. In the late 1970s, the mere association with modernist architecture or urban design was enough to condemn you. Now it makes you more interesting.

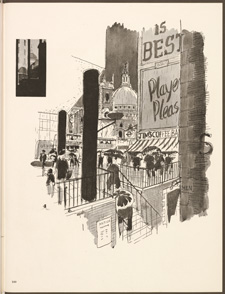

What makes Pevsner's work applicable to present issues is its visuality and its comprehensive approach to the built environment. He and Hubert de Cronin Hastings (the Architectural Review's chief editor) were looking at the messy vitality of the urban scene and seeing how an artistic view of it could be brought back within the realm of design and art.

You see similar ideas today with architects who are working in enormous cities in China. They like to look at the qualities of these cities in a visual way and understand what they mean (for example, Rem Koolhaas's work on the Pearl River delta). Before that there was Learning from Las Vegas (1972); both are similar attempts to elevate the lowly to something more highly valued.

But if you fast-forward 20 years, people became interested in Pevsner again for the same reasons that they were not interested in him in the late 1970s.

That is, Townscape is a very modern movement. This is something that has fallen by the wayside. Most people think that Townscape was about making tasteful street furniture or lighting, seats, benches, and litterbins to match an urban design scenario. They absolutely do not think that it's about modern architecture adapted in a very free-form way to concrete problems of reconstruction.

Today's interest in Pevsner's work, in Townscape and visual planning—indeed, in the mid-century architectural and urban design milieu—has to do with the rekindled interest in modernism as something that is not inherently flawed. In the late 1970s, the mere association with modernist architecture or urban design was enough to condemn you. Now it makes you more interesting.

What makes Pevsner's work applicable to present issues is its visuality and its comprehensive approach to the built environment. He and Hubert de Cronin Hastings (the Architectural Review's chief editor) were looking at the messy vitality of the urban scene and seeing how an artistic view of it could be brought back within the realm of design and art.

You see similar ideas today with architects who are working in enormous cities in China. They like to look at the qualities of these cities in a visual way and understand what they mean (for example, Rem Koolhaas's work on the Pearl River delta). Before that there was Learning from Las Vegas (1972); both are similar attempts to elevate the lowly to something more highly valued.

Were you surprised that Pevsner put forward gardening as the theoretical model for urban planning?

It's a shocking conjunction: connecting 18th-century landscape gardening and picturesque principles with mid-20th century British problems. It can probably be traced back more to Hastings and his eccentric, wide-ranging interests.

But it's also very Pevsnerian because it is transhistorical. In Part II, Pevsner is combing the picturesque for concepts, techniques, principles (as he terms them), that are useful in organizing present-day urban design.

But it's also very Pevsnerian because it is transhistorical. In Part II, Pevsner is combing the picturesque for concepts, techniques, principles (as he terms them), that are useful in organizing present-day urban design.

|

|

Keep in mind that there are also other issues. During the war, the picturesque sounded very British, and the history of landscape gardening is associated with Britain. If you're going to propose a new urban design movement in 1945, you want to make it sound very British.

Also, in making the leap between 1930s and 1940s Britain and 18th-century landscape gardeners and treatise writers, Pevsner and Hastings omitted some people who were more related and closer at hand—and some who were not British.

A clear lineage starts in Britain in the 18th century and develops in the early 19th century with John Nash and his very informal, irregular picturesque, a haphazard style of planning that he carries out in London.

After Nash it becomes a German story. If you understand the ideas behind German movements such as Stadtbaukunst or "the art of city planning" (proposed by Camillo Sitte and those around him), then you know that this romantic, irregular, informal, or picturesque version of urban design starts to be taken up in Germany.

Fast-forward to the end of the 19th century and the body of work that emerged with Kunstwissenschaft, the German "science of art." Pevsner bases his understanding of what this discipline is about—his very raw understanding in the 1920s and 1930s—on these discourses. Pevsner encountered this lineage in Germany, but it became operative in the mid-20th century Britain.

Also, in making the leap between 1930s and 1940s Britain and 18th-century landscape gardeners and treatise writers, Pevsner and Hastings omitted some people who were more related and closer at hand—and some who were not British.

A clear lineage starts in Britain in the 18th century and develops in the early 19th century with John Nash and his very informal, irregular picturesque, a haphazard style of planning that he carries out in London.

After Nash it becomes a German story. If you understand the ideas behind German movements such as Stadtbaukunst or "the art of city planning" (proposed by Camillo Sitte and those around him), then you know that this romantic, irregular, informal, or picturesque version of urban design starts to be taken up in Germany.

Fast-forward to the end of the 19th century and the body of work that emerged with Kunstwissenschaft, the German "science of art." Pevsner bases his understanding of what this discipline is about—his very raw understanding in the 1920s and 1930s—on these discourses. Pevsner encountered this lineage in Germany, but it became operative in the mid-20th century Britain.

|

|

In many ways Pevsner closes the circle on picturesque planning, from Britain to Germany and back to Britain. This curious story would have been easier to read had Britain not been at war with Germany at the time.

After the war is over, in the 1950s and 1960s, these references and sources start to flow again. Pevsner makes reference to Raymond Unwin, who makes reference to Sitte, and so this lineage is exposed for what it is. But it is an unusual route.

That's part of the idiosyncrasy of this movement. It is hard to apply catchwords and a rigid agenda to it because it was continuously evolving. What Pevsner and Hastings were doing in the 1940s—indeed what visual planning was—differs slightly in the 1950s, and then was very different in the 1970s.

I would suggest that is partly why the manuscript was never published. It had become passé and even was eclipsed by other works coming out in the late 1950s and 1960s.

After the war is over, in the 1950s and 1960s, these references and sources start to flow again. Pevsner makes reference to Raymond Unwin, who makes reference to Sitte, and so this lineage is exposed for what it is. But it is an unusual route.

That's part of the idiosyncrasy of this movement. It is hard to apply catchwords and a rigid agenda to it because it was continuously evolving. What Pevsner and Hastings were doing in the 1940s—indeed what visual planning was—differs slightly in the 1950s, and then was very different in the 1970s.

I would suggest that is partly why the manuscript was never published. It had become passé and even was eclipsed by other works coming out in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Visual Planning engages a fundamental tension between specific historical moments—for example, rebuilding the city of London after the war—and principles that can be found in sources across centuries. How do you see these principles at work?

If you scrape away the rhetoric that this is all about Englishness, you understand that Pevsner is seeing the picturesque as a series of techniques that are not logically limited to any one nation. But originally, he thought this association with the picturesque would make these ideas more palatable to the British public.

What enabled me to see those principles work as Pevsner did was most certainly the work of John Macarthur. He had written a brilliant book on the picturesque that sees it much in the way that Pevsner did. But he extends that use to the present and into other fields like art history, gardening, urbanism, and architecture. So I'm coming out of that school of thought.

What enabled me to see those principles work as Pevsner did was most certainly the work of John Macarthur. He had written a brilliant book on the picturesque that sees it much in the way that Pevsner did. But he extends that use to the present and into other fields like art history, gardening, urbanism, and architecture. So I'm coming out of that school of thought.

Today the picturesque connotes inoffensive pleasantness. But in Pevsner's time, it meant something vulgar, crude, or even ugly. Does its shifting meaning pose a challenge?

That is one of the biggest difficulties. When we talk about picturesque, what picturesque are we referring to?

When we're talking about it in relationship to Townscape, we always pitch it as a kind of hard and soft Townscape, both of which remained active throughout its duration. Soft Townscape is about whimsy, romanticism, and sentiment. The hard picturesque of Pevsner and Hastings gives you principles and theory: irregularity, variety, contrast, impropriety.

These "hard-edged" principles would be the foundation of a new approach to architecture and urban design. In 1954 Pevsner went so far as to say that the fundamentals of the modern movement are the same as those of the picturesque. That caused an outcry among the architects and critics of his own time! But that's what he thought modern architecture was doing, insofar as it was informal and irregular, and it combined different materials.

This was a massive departure from a classical understanding of architecture. The idea that he could call modern architecture picturesque gives you insight into how he saw the picturesque. It wasn't necessarily about whimsy and sentiment and romanticism.

That's not to say that those themes weren't in the campaign from the 1940s and 1950s. Indeed, others focused on those values, for example, John Betjeman and John Piper.

So, there are different approaches, and I think reading Visual Planning gives a firm understanding of how Pevsner saw the picturesque. Unfortunately, the intervening 60 years since the book was begun have not cleared the muddy waters surrounding the meaning and significance of picturesque in contemporary discourses of architecture and urban design.

When we're talking about it in relationship to Townscape, we always pitch it as a kind of hard and soft Townscape, both of which remained active throughout its duration. Soft Townscape is about whimsy, romanticism, and sentiment. The hard picturesque of Pevsner and Hastings gives you principles and theory: irregularity, variety, contrast, impropriety.

These "hard-edged" principles would be the foundation of a new approach to architecture and urban design. In 1954 Pevsner went so far as to say that the fundamentals of the modern movement are the same as those of the picturesque. That caused an outcry among the architects and critics of his own time! But that's what he thought modern architecture was doing, insofar as it was informal and irregular, and it combined different materials.

This was a massive departure from a classical understanding of architecture. The idea that he could call modern architecture picturesque gives you insight into how he saw the picturesque. It wasn't necessarily about whimsy and sentiment and romanticism.

That's not to say that those themes weren't in the campaign from the 1940s and 1950s. Indeed, others focused on those values, for example, John Betjeman and John Piper.

So, there are different approaches, and I think reading Visual Planning gives a firm understanding of how Pevsner saw the picturesque. Unfortunately, the intervening 60 years since the book was begun have not cleared the muddy waters surrounding the meaning and significance of picturesque in contemporary discourses of architecture and urban design.

3. Pevsner as Engaged Critic

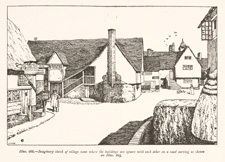

In Part I, Pevsner includes several walking tours—photo essays that guide the reader visually and verbally through a neighborhood. How do Pevsner's tours work?

Take Pevsner's walking tour of Queen's Lane, Oxford

I think the walking tour is an incredibly successful motif. It was used by several people at the Architectural Review, although Pevsner's tours differed. Pevsner is looking at the architectural detail: the way the form, material, and age of a building are part of a larger coordinated and choreographed idea about contrasting these things and creating an experience for the moving subject in the urban setting.

Part I shows the reader familiar scenes and tells us what we should be looking for. It is a classic tour guide's approach, but he doesn't tell us the story of the building and what Duke such-and-such did in 1605 when they were there.

Once again he takes a transhistorical approach; it's a technique, seeing building as a substance, the raw material of experience. Once the reader understands these techniques, we can apply them. They can be extracted from Cambridge or Oxford, or even Bath, and be applied to our regional shopping centers. That's partly what Pevsner was about.

Through those tours he comes across some quite particular observations—for example, this idea of a collegiate planning, or precinctual planning as he terms it, which is about outdoor space, the way it is negotiated by a moving viewer, and how the possibilities of architecture and urban design can be informed by the way that outdoor spaces are arranged. It's quite an ingenious approach.

Early on, he contrasts what designers did in a beaux-arts and "grand manner" planning mode, where everything is symmetrical, with a very British, informal, and irregular style of planning, and notes how different our modes of appreciation must be in order to see those. I think that's a very successful ruse.

One other thing I would mention: Pevsner was criticized towards the end of his career, not only because of his support of modern architecture but also for his views on the role of historians, for his "operative" use of history, and for mixing these roles as historian and as critic.

Pevsner didn't mistake these two roles. He thought they were related. This book also has something to say about that issue. We look to history to see how the past has shaped the present, and how that could be done in the future. That's very clearly what Pevsner's doing.

It becomes a problem when it becomes dogmatic and doctrinaire insofar as when Pevsner starts to discount particular architects, architecture, or urban design because they are not conforming to some preconceived idea about what history is suggesting.

But what we also see in this book is that Pevsner is clearly outlining these different roles and showing us what use history can be in his present day, the 1950s.

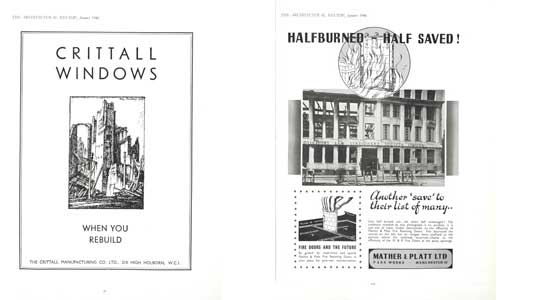

Does the critique of Pevsner as an operative historian misjudge the forum? After all, the Architectural Review was attempting to influence architects rebuilding after the war, as the numerous ads in each issue reveal.

That was the whole point of Hastings saying to Pevsner, "I'd like you to write a book about visual planning and the picturesque." Hastings wanted it to be popular. Not only did he want it to be popular, but he also wanted these theoretical and conceptual aspects—perhaps in less scholarly terms—portrayed as the historical backbone to this movement.

So it was intended to be popular and appealing from the very beginning. There are very few scholarly works that came out of the Architectural Press, the publishing arm of the Architectural Review. They are very much polemics for a particular point of view, not scholarly treatments of a particular subject.

So it was intended to be popular and appealing from the very beginning. There are very few scholarly works that came out of the Architectural Press, the publishing arm of the Architectural Review. They are very much polemics for a particular point of view, not scholarly treatments of a particular subject.

So it's very clear how that book has to perform. But this mode of topical publishing gets confused when Hastings asks a historian to write the book, and the historian doesn't finish it.

Instead, seven or eight years after Pevsner seems to have put this down, Gordon Cullen, art editor and one of the chief players in illustrating and documenting Townscape, published his book on Townscape, which became a best seller. Indeed, the abridged version of it, The Concise Townscape, is still in print today. These things were published, and they contain virtually none of the historical, theoretical, or conceptual research that Pevsner had done.

How did the look of the Architectural Review combine the formal and the informal?

|

|

The Architectural Review makes a very strong visual impression. That's implicit: it's a magazine. You have to sell copies and make it look new all the time. It has to be visually striking.

But its design is a corollary to the way they saw architecture and urban design—having serif and sans-serif fonts within a single book, a very clean layout contrasted with Victorian typefaces and floral typefaces, or ornamented captions and icons. This is what they were proposing at the scale of a city: that there could be the clean modern building sitting next door to the shabby Victorian building, and both could be around the corner from some abstract art, all set within the gloomy gray of a British sky.

In effect, that is why they proposed the visual planner: to coordinate and choreograph that whole scene. So that variety could and should coexist. They demonstrate that very clearly and very early.

But its design is a corollary to the way they saw architecture and urban design—having serif and sans-serif fonts within a single book, a very clean layout contrasted with Victorian typefaces and floral typefaces, or ornamented captions and icons. This is what they were proposing at the scale of a city: that there could be the clean modern building sitting next door to the shabby Victorian building, and both could be around the corner from some abstract art, all set within the gloomy gray of a British sky.

In effect, that is why they proposed the visual planner: to coordinate and choreograph that whole scene. So that variety could and should coexist. They demonstrate that very clearly and very early.

If you pick up any edition from the late 1940s or the 1950s, you see many illustrations and layouts that show that same mixture of tradition and contemporary, of formal and irregular, and many other distinctive juxtapositions.

We tried to have this come through in the Visual Planning and the Picturesque book. We were very keen to have the book's style drawn from the 1940s Architectural Review and for the overall design to feel like the period.

We tried to have this come through in the Visual Planning and the Picturesque book. We were very keen to have the book's style drawn from the 1940s Architectural Review and for the overall design to feel like the period.

4. The Future of Townscape

How do people react when you say that you're interested in Townscape?

|

|

People often assume that I am a new urbanist, or that I am into conservation or historicist architecture and urban design. Personally, I am not into those things. This association is a curious twist of history because it couldn't be further from the original intentions of people like Pevsner and Hastings.

They were advocating an architecture and urban design that was very much of its own age and new. That this body of thought has become aligned in recent times with things like the new urbanism in the United States, or with the faux-historical villages proposed by Prince Charles and others is curious, but not completely unexplainable.

They were advocating an architecture and urban design that was very much of its own age and new. That this body of thought has become aligned in recent times with things like the new urbanism in the United States, or with the faux-historical villages proposed by Prince Charles and others is curious, but not completely unexplainable.

|

|

Townscape wasn't so focused that multiple readings couldn't come about. In the 1960s and 1970s, it takes on a much more preservationist bent than in the 1940s and 1950s. These are parallel legacies.

Several scholars, including myself, have been trying to illustrate this earlier, harder version of Townscape—a version that's less nostalgic than the received version that's about preservation, conservation, and nostalgia for historicist architecture and urban design.

Several scholars, including myself, have been trying to illustrate this earlier, harder version of Townscape—a version that's less nostalgic than the received version that's about preservation, conservation, and nostalgia for historicist architecture and urban design.

Do you have thoughts about the contemporary application of visual planning? Reading Visual Planning, I think of New Orleans or Port-au-Prince.

When one discovers a work like this, written by such a prominent architectural historian, it's tempting to say that this is somehow the missing link or the answer. But we have to be clear that the book's primary importance is historical, in understanding what happened, when, and by whom.

Looking at the examples that you're mentioning brings me to one of the major criticisms of the type of work that we're doing: what they were advocating in Townscape, and indeed Pevsner advocates in Visual Planning and the Picturesque, is incredibly formalist. They're not talking about social values, technology, infrastructure, or any of the things that underpin urban planning. They're talking about visual appreciation.

So we have to be careful. But it is interesting when you see these techniques or principles, which can be abstracted and developed, as ideas in a contemporary architectural or urban design setting.

That's where I come back to visuality and how this understanding of the picturesque allows us to see a comprehensive view of the urban scene. This view is not filtered by taste or style, but enables us to take in the messy vitality of an urban scene without being selective. That's something I take forward with me.

Townscape has also been influential in conceptualizing what we now call the built environment. That is, seeing it as a holistic thing that needs to be approached as a totality. We don't have interior designers, landscapers, architects to do buildings, urban planners to lay out roads, and urban designers to lay out footpaths and do street furniture. The visual planner, as Pevsner saw it, was somebody who stands as a captain of all these roles, and that is their true responsibility.

That's something that I think has the potential for a contemporary application: this total view of architecture, urban design, urban planning, and landscape design. That was very new back then. I think it's still relevant today and something that's largely been forgotten.

Looking at the examples that you're mentioning brings me to one of the major criticisms of the type of work that we're doing: what they were advocating in Townscape, and indeed Pevsner advocates in Visual Planning and the Picturesque, is incredibly formalist. They're not talking about social values, technology, infrastructure, or any of the things that underpin urban planning. They're talking about visual appreciation.

So we have to be careful. But it is interesting when you see these techniques or principles, which can be abstracted and developed, as ideas in a contemporary architectural or urban design setting.

That's where I come back to visuality and how this understanding of the picturesque allows us to see a comprehensive view of the urban scene. This view is not filtered by taste or style, but enables us to take in the messy vitality of an urban scene without being selective. That's something I take forward with me.

Townscape has also been influential in conceptualizing what we now call the built environment. That is, seeing it as a holistic thing that needs to be approached as a totality. We don't have interior designers, landscapers, architects to do buildings, urban planners to lay out roads, and urban designers to lay out footpaths and do street furniture. The visual planner, as Pevsner saw it, was somebody who stands as a captain of all these roles, and that is their true responsibility.

That's something that I think has the potential for a contemporary application: this total view of architecture, urban design, urban planning, and landscape design. That was very new back then. I think it's still relevant today and something that's largely been forgotten.

How do you see Pevsner or Townscape reaching out to the visual arts?

Hastings's editorial philosophy was to put many different people from diverse backgrounds together: working at the magazine there was a surrealist, a new romantic painter, a poet, a cartoonist, a more straight-up-and-down town planner, some of the foremost architects and architectural writers of the day, and the two most prominent architectural historians of their day, Pevsner and John Summerson.

There is an enormous breadth to the Townscape campaign, and so many aspects to study. One could start with the magazine's layout, its design, the paper, and the fonts. Much like the type of architecture and urban design they were pushing, the Architectural Review's look was supposed to be something similar, and was equally influenced by cubism, surrealism, and later neoromanticism.

In 2010 I spoke at a conference about writing and architecture. It was a wonderful opportunity to talk about the Townscape campaign within the Architectural Review, exactly how rich it was, and how strange that seems in today's publishing world. That you could have people writing about such fanciful things!

There is an enormous breadth to the Townscape campaign, and so many aspects to study. One could start with the magazine's layout, its design, the paper, and the fonts. Much like the type of architecture and urban design they were pushing, the Architectural Review's look was supposed to be something similar, and was equally influenced by cubism, surrealism, and later neoromanticism.

In 2010 I spoke at a conference about writing and architecture. It was a wonderful opportunity to talk about the Townscape campaign within the Architectural Review, exactly how rich it was, and how strange that seems in today's publishing world. That you could have people writing about such fanciful things!

Where do you see scholarship on Townscape going from here?

I have organized a symposium in London on July 22–23, 2011, which looks at the reception of and scholarship on Townscape and this period within the Architectural Review. Most of the scholars who are working on this area will be there to talk about their efforts. There are many ways to approach that period at the Architectural Review and Townscape; I think it makes it a really interesting subject of discussion and research.

I'm also working on a monograph on Townscape (the first of its kind) that opens this material up again—much in the way that the Visual Planning book does. The book should have many illustrations, not only because much of this material has been forgotten and is so spectacular but also because it is the most succinct way to see what Townscape, as a principally visual campaign, was about. But the book is still at least a year away.

I'm also working on a monograph on Townscape (the first of its kind) that opens this material up again—much in the way that the Visual Planning book does. The book should have many illustrations, not only because much of this material has been forgotten and is so spectacular but also because it is the most succinct way to see what Townscape, as a principally visual campaign, was about. But the book is still at least a year away.

Related work by Mathew Aitchison:

Mathew Aitchison, "Who's Afraid of Ivor de Wolfe," AA Files 62 (2011): 34–39.

John Macarthur and Mathew Aitchison, "Oxford vs. the Bath Road: Empiricism and Romanticism in the Architectural Review's Picturesque Revival," Journal of Architecture (forthcoming).

John Macarthur and Mathew Aitchison, "Oxford vs. the Bath Road: Empiricism and Romanticism in the Architectural Review's Picturesque Revival," Journal of Architecture (forthcoming).