The Metropolis in Latin America, 1830–1930

By Idurre Alonso and Maristella Casciato

Sociopolitical upheavals and cultural transitions reshaped the architectural landscapes of major cities in Latin America during a century of rapid urban growth. Radical breaks with the colonial past, transformative architectural exchanges with Europe and beyond, and the subsequent reinterpretation of pre-Hispanic, Spanish, and Portuguese motifs influenced the emergence of a modernist culture and a modern architectural idiom.

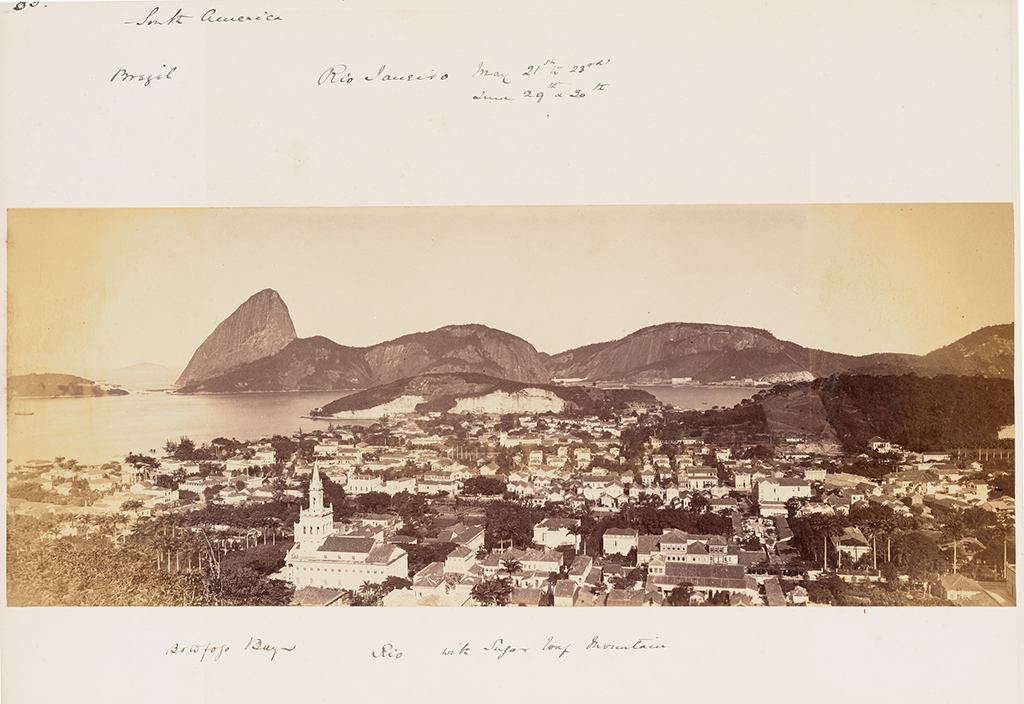

This exhibition presents the colonial city as the urban model imposed by the Iberian powers, and the new republican city as a transfer of sources and technical knowledge that were eventually appropriated, interpreted, and later subverted through a wave of revivals. Following this narrative, The Metropolis in Latin America, 1830–1930, reveals how six capitals—Buenos Aires, Havana, Lima, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, and Santiago de Chile—were transformed from colonial cities into monumental republican metropolises. Photographs, prints, plans, and maps depict the urban impact of key socioeconomic changes, including the emergence of a bourgeois elite, extensive infrastructure projects, and rapid industrialization and commercialization.

Download the English wall texts from the gallery.

Descargue los textos de la galería en español.

The Colonial City

In 1502 the Spanish Empire founded Santo Domingo, the first urban settlement in the Americas, on the island of Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic and Haiti). Its design was based on a grid of blocks organized around a main plaza. The cathedral, along with the town hall (cabildo), presided over the plaza, centralizing commercial, religious, and political activity. Known as a cuadrícula española (Spanish grid), this urban arrangement was codified in edicts by Spanish kings Carlos V and Felipe II in 1526 and 1573, respectively, as part of the Laws of the Indies (Leyes de Indias). These edicts constituted the first written regulations on town planning in the Americas. Not only did the codes guide the development of commercially functional and militarily strategic cities, they projected images of power onto newly subjugated populations. Town planning became a key tool of the colonial enterprise. This colonial urban model was followed—with some modifications—in the design of numerous towns and cities throughout Latin America over the next two centuries.

The Republican City

Following independence, Latin Americans had an urgent need to break with the colonial past. This was expressed through architecture and urban planning. Many symbols of colonialism were removed or diminished through the construction of new civic buildings such as parliaments, ministries, banks, theaters, and universities. Through major social, demographic, and economic transformations including large-scale migration to cities, industrialization, and market-based economic reforms, cities were fundamentally reconfigured.

In Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, and other capitals, a fascination with the Parisian grands travaux (great works) of the Second French Empire (1852–1870) resulted in the adoption of European planning models. Radial networks of avenues, as well as new parkways, public parks, and botanical gardens transformed the cities' landscapes. Despite such changes, the legacy of the colonial city was not completely lost in this period. The plaza, for example, remained a key social and cultural center.

Spaces for Leisure and Culture

The emergence of an urban bourgeoisie propelled the growth of outdoor spaces for leisure such as promenades, public parks, and botanical gardens. Lined with trees and dotted with benches, fountains, and streetlights, boulevards became performance sites for new urban rituals. The well-to-do strolled along the avenues not only to access new cultural spaces including theaters, cinemas, and museums but also to see and be seen. Electric-powered streetcar lines traversed newly paved streets, enabling access to modern amenities. Forts and harbors from the colonial era were redesigned as residential areas and promenades. Seeking to incorporate "wild" landscapes into cities, urban planners created largescale projects that reshaped nearby natural features such as Rio de Janeiro's Corcovado Mountain, Santiago de Chile's Santa Lucía Hill, and Mexico City's Chapultepec Forest.

Many of these urban renewal and city beautification projects bore the signature of European professionals. Perhaps the most notable is French landscape architect Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier (1861–1930). In 1924, he designed several parks and other leisure areas for Buenos Aires' master plan, which echoed Paris during the Second Empire.

Modern Infrastructure

By the last quarter of the 19th century, with populations booming across Latin America's urban centers, issues like sanitation, waste management, and transportation came to the fore. Various social reform movements targeted the metropolis by encouraging large infrastructure projects like bridges, railways, aqueducts, and sewage systems. Such projects addressed various urban problems by fostering the movement of people, goods, and waste across wider regions.

Economies in the region benefited from this attention to infrastructure: the smoother exchange of commodities and services produced a series of economic booms, with cities progressively turning to commerce, industry, and export-oriented production. Increases in trade spurred the expansion of existing ports and the creation of new ones. These transformations improved the quality of life for many and provided the means for the emergence of a new economy based on industrialized, capitalist models.

National Architecture in Context

In the 1910s grandiose celebrations across Latin America marked one hundred years of independence. These commemorations sparked a reassessment of national identity. Architects, planners, and politicians initiated a return to local architectural traditions, eschewing European models in favor of pre-Hispanic and colonial ones. National pavilions designed for the Paris (1889), Panama-California San Diego (1915), and Ibero-America Seville (1929) expositions showcased how Latin American countries called up native architectural idioms in order to foster their identities.

Concurrently, Southern California architects drew on an idealized historical past to create a new, hybrid architectural identity—Mission Revival style—which then rapidly spread throughout Latin America. Meanwhile, the growing popularity of pre-Hispanic exhibits at world's fairs and the turn toward pre-Columbian cultures in the modern study of archaeology resulted in the emergence of a Mayan revival. This style can be seen in the seminal work of architects Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), his son Lloyd Wright (1890–1978), and Robert Stacy-Judd (1884–1975).

Toward Modernism

In the first decades of the 20th century, a new generation of Latin American designers turned to the metropolis to establish utopias for all. Whether educated in Europe or at new architecture and civil engineering schools in Latin America, they worked side by side with European champions of modern urbanism. The French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier (1887–1965) and the German planner Werner Hegemann (1881–1936) were among those who most notably contributed to planning debates. While the former strongly critiqued the colonial grid and delivered a visionary message of modernity, the latter advocated a more pragmatic plan based on the different zones of the city and their varying functions.

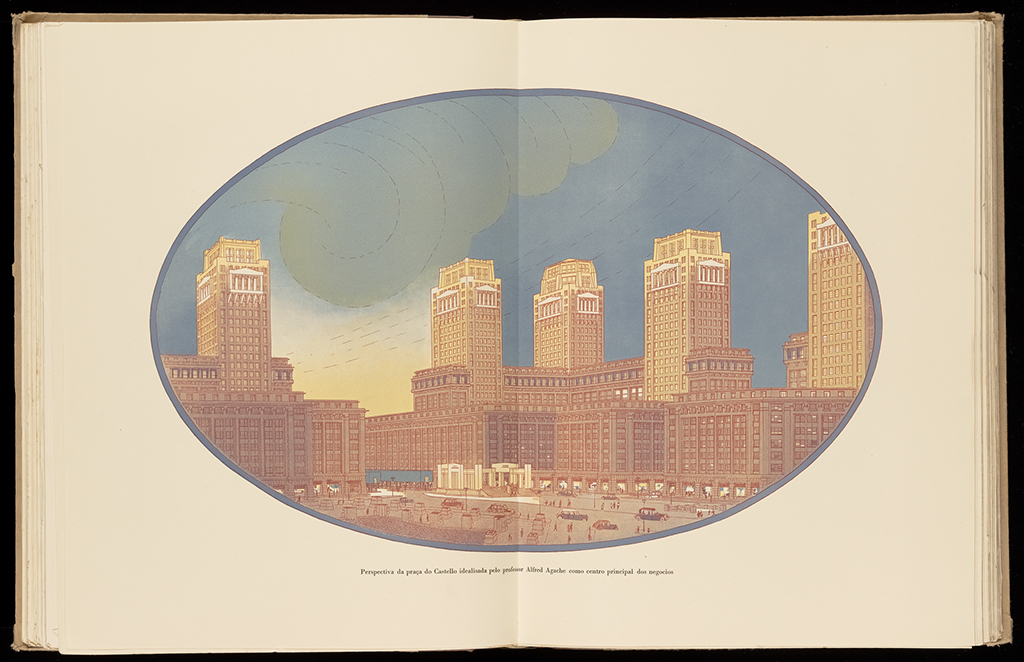

Through opposing experimental positions, the metropolis in Latin America became a laboratory where scientific planning mingled with a romantic attachment to natural environments. The work of French urban planner Alfred Agache (1875–1959), who came to Brazil from 1926 to 1930 to coordinate a master plan for Rio de Janeiro, and the proposal of an Argentine ville radieuse (radiant city) by Russian émigré Wladimiro Acosta (1900–1967) embodied the forward-looking approaches of a region on the verge of major changes.