Bauhaus Beginnings

Text by Maristella Casciato and Gary Fox with Alexandra Sommer and Johnny Tran

Founding the Bauhaus

The Bauhaus officially opened in Weimar, Germany on April 1, 1919. Director Walter Gropius's manifesto announced a bold vision for the newly reformed, state-sponsored school of art and design. In a text laden with spiritual and romantic imagery, Gropius outlined a model of education that bridged the fine and applied arts. He hoped that various forms of artistic practice—especially painting, sculpture, architecture, and design—could produce socially and spiritually gratifying collective works. The internationally circulated manifesto idealized the medieval past as a model for the transformation of modern arts education, attracting students from as far away as Japan to the school.

Download the complete wall texts from the gallery.

Bauhaus Woodcuts

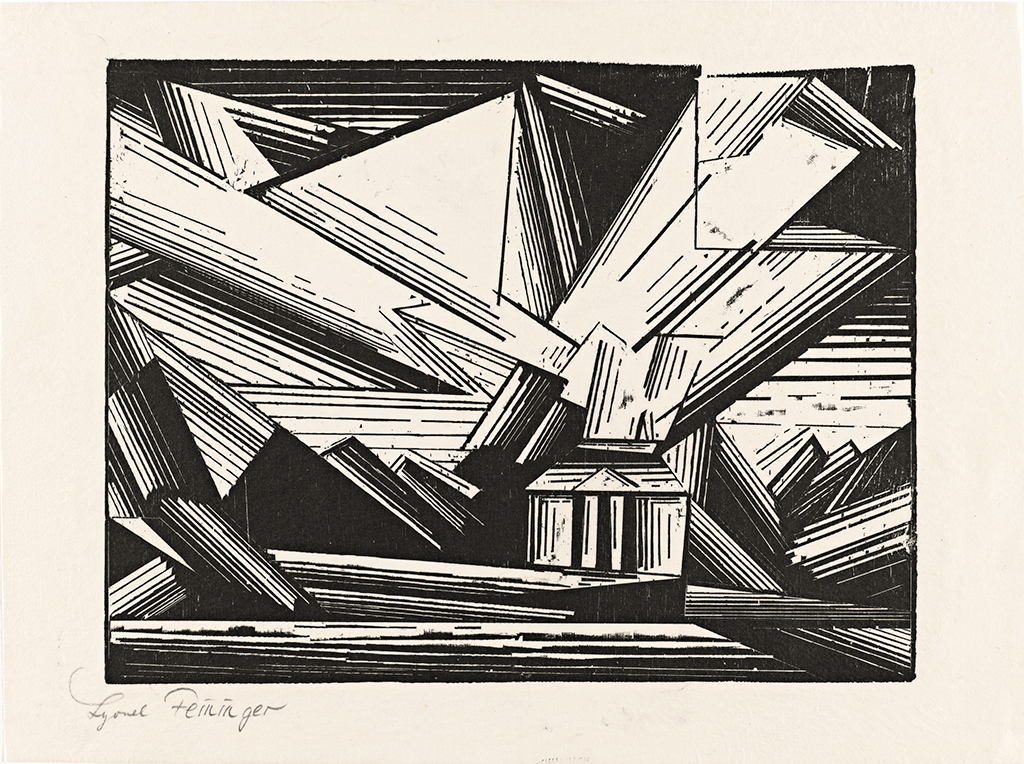

Woodcuts occupied a central role at the early Bauhaus. As a centuries-old printing technique, the woodcut came to be associated with the Romanticism and expressionism that coursed through the Bauhaus in its beginning phase. The German expressionists—committed to the subjective, emotional, and spiritual facets of design—revived and celebrated this preindustrial form of art.

The first publication issued by the Bauhaus print workshop was Lyonel Feininger's portfolio Zwölf Holzschnitte (Twelve woodcuts) in 1921. The stark black-and-white prints reimagine urban scenes and naval seascapes in jagged forms that were highly characteristic of the woodcut as a medium. Gerhard Marcks, who, like Feininger, was among the first to be hired at the Bauhaus in 1919, published a series titled Das Wielandslied der älteren Edda (The Wieland song of the elder Edda) a few years later. Illustrating the Germanic myth of a legendary master blacksmith, the prints are an allegorical reflection on a Romantic, preindustrial past. Expressionism and spirituality, associated with the woodcut, were highly influential among students and visible in works such as the student journal Der Austausch (The exchange).

Form and Color; or, The Fundamentals

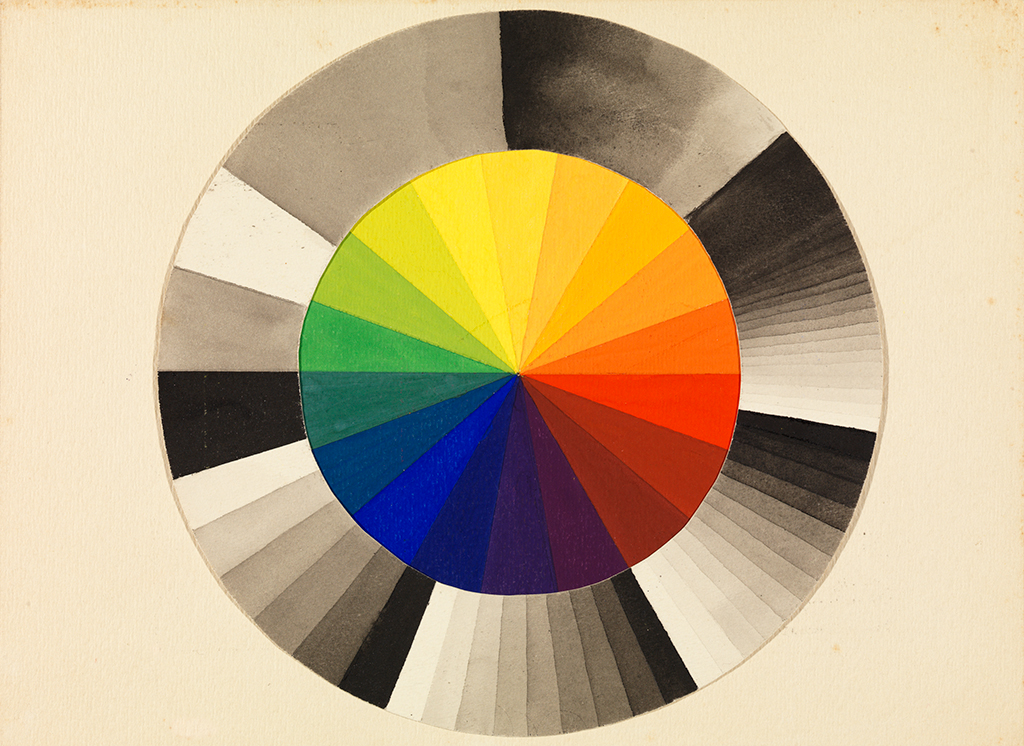

The Preliminary Course at the Bauhaus introduced all first-year students to what were considered the fundamental principles of color, form, and material. Through lectures, demonstrations, and exercises, they were to develop familiarity with the "basic elements" of art and design, including points, lines, and planes; triangles, squares, and circles; and the primary colors. Teachers aimed to promote a shared foundation of aesthetic knowledge among the student body through these investigations.

The Bauhaus masters—each armed with his or her particular theories and interests—spearheaded the first-year studies. Johannes Itten initiated the Preliminary Course in the fall of 1920; László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers took over beginning in 1923. Albers led it alone after 1928. These courses were supplemented by specialized theoretical seminars taught by key Bauhaus faculty, including Gertrud Grunow, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, and Joost Schmidt. The masters agreed that a firm grounding in the principles of form and color was crucial to the development of a new generation of artists. These fundamentals remained at the core of Bauhaus education until the closure of the school in 1933.

Interaction of Color

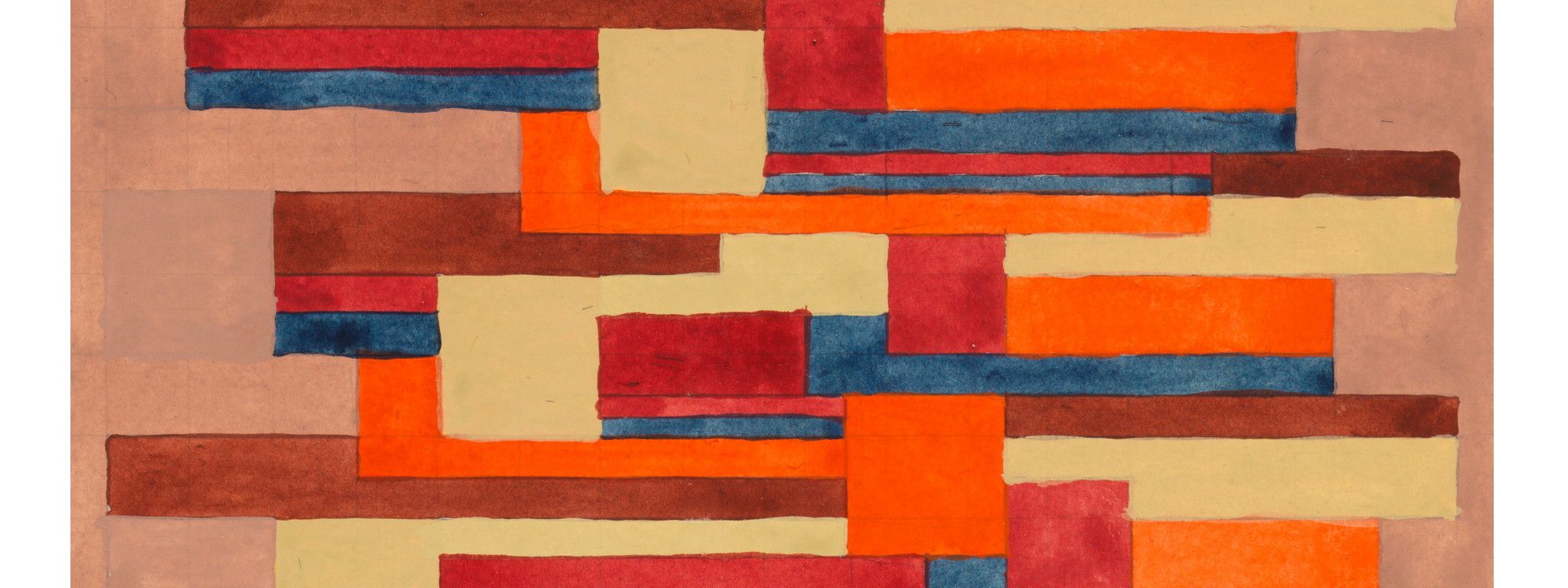

In the Preliminary Course, students tested interactions among two, three, or four colors. To encourage students to think of color as a phenomenon independent of form, Johannes Itten devised a system of colored cutouts that could be placed side by side or on top of one another. His students placed these amid other media to explore the spatial effects and the changes to hue, value, or intensity brought about by arranging and combining colors.

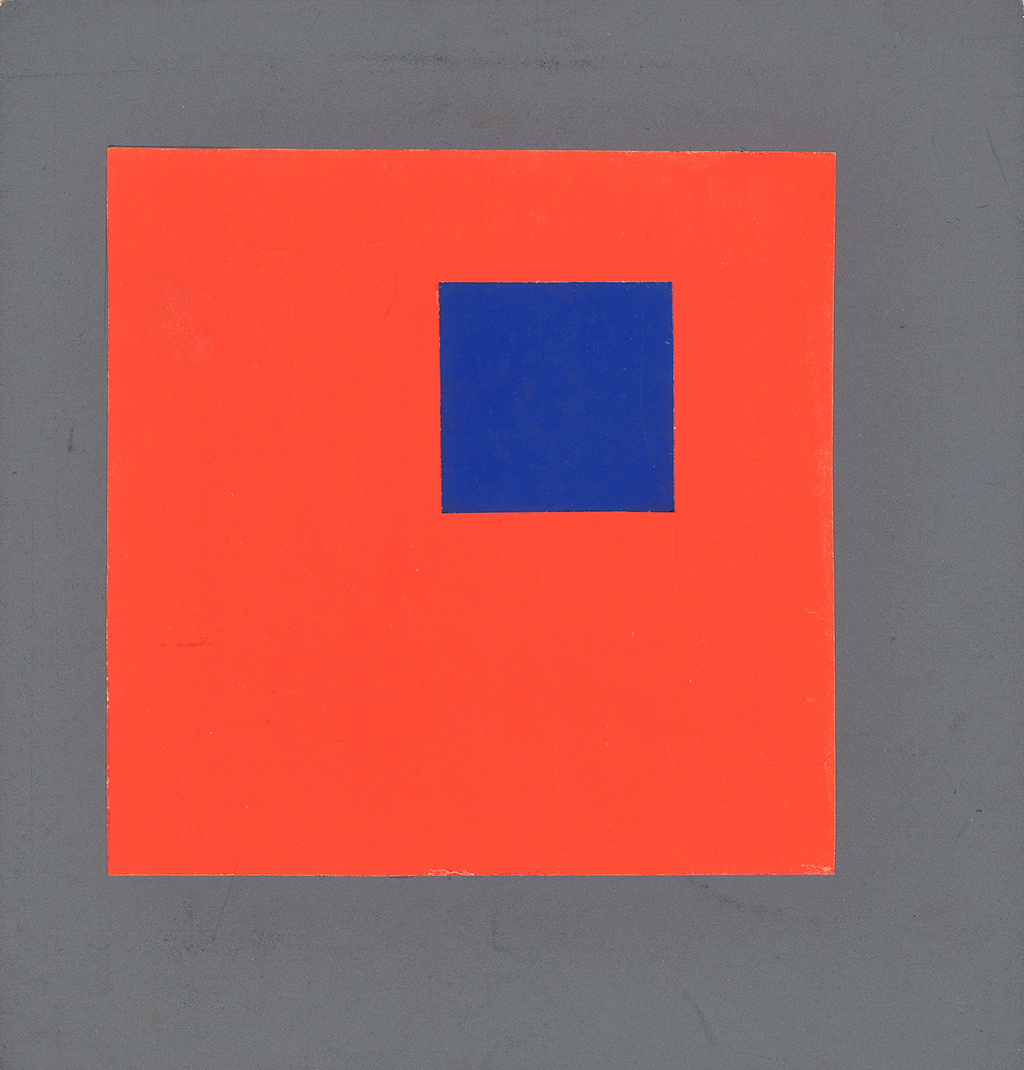

Vassily Kandinsky similarly championed the use of cutouts, having students position colored

rectangles, squares, and circles in various configurations. Exercises often involved arraying these elements on a grid or within a square, constraining formal possibilities. Paul Klee developed a series of related exercises in watercolor. Fields of color, restricted to geometries

such as circles and triangles, could intersect and overlap to test relativity and transparency. These studies allowed students to explore polarities such as light versus dark, warm versus cold,

active versus passive, and receding versus advancing.

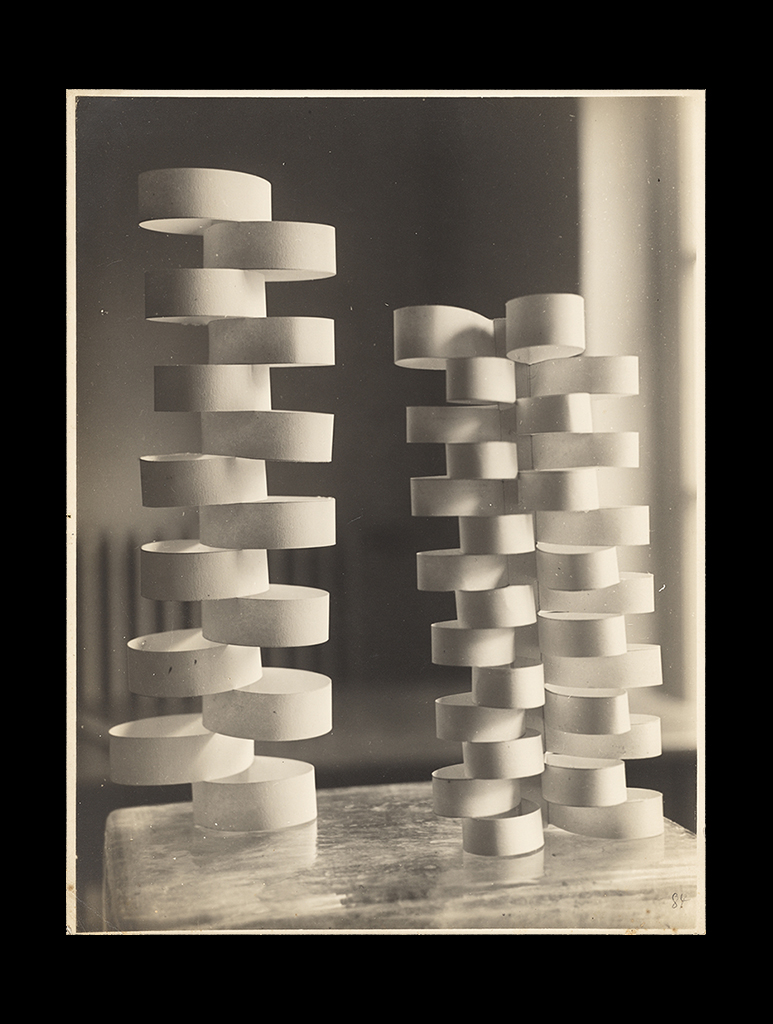

Material Studies

Students were expected to develop familiarity with a wide variety of materials—including wood, glass, fiber, paper, and metal—priming them for entry into specialized workshops.

Both Johannes Itten and Josef Albers contributed to the development of material studies in the Preliminary Course. Each considered the learning process to be experiential and tactile, foregrounding the sensorial comprehension of textures and contrasts. Influenced by pioneering 19th-century educator Friedrich Fröbel's ideas about learning through play, Itten asked students to develop collages and assemblages from found materials. Sticks, wire, fabric, paper,

and glass were arranged together to engage the sense of touch, the feeling of texture, and the perception of essence. Albers, by comparison, insisted that students work in harmony with the essential character of a single material; studies in his course explored the structural and conceptual limits of materials.

Weaving

Although women were admitted to the Bauhaus in relatively large numbers—in its first year, about half the enrolled students were women—they did not share equal status with their male peers. The majority of women students were pressured to study weaving, rather than other disciplines such as metal-working or architecture, despite their objections.

In the aftermath of World War I, materials and funds for the school's workshops were scarce, and the weavers used original looms from the School of Applied Arts to produce one-off objects

such as stuffed animals and dolls. Early Bauhaus master Helene Börner instructed weaving students to draw upon foundational theories of color and form developed in the Preliminary Course to produce innovative designs.

When former student Gunta Stölzl became director of the weaving workshop in 1926, she argued that "a woven piece is always a serviceable object," pushing production away from the loom and toward industrial modes. Bauhaus textiles were manufactured in bulk and sold widely, rendering them one of the most successful and broadly disseminated Bauhaus products.

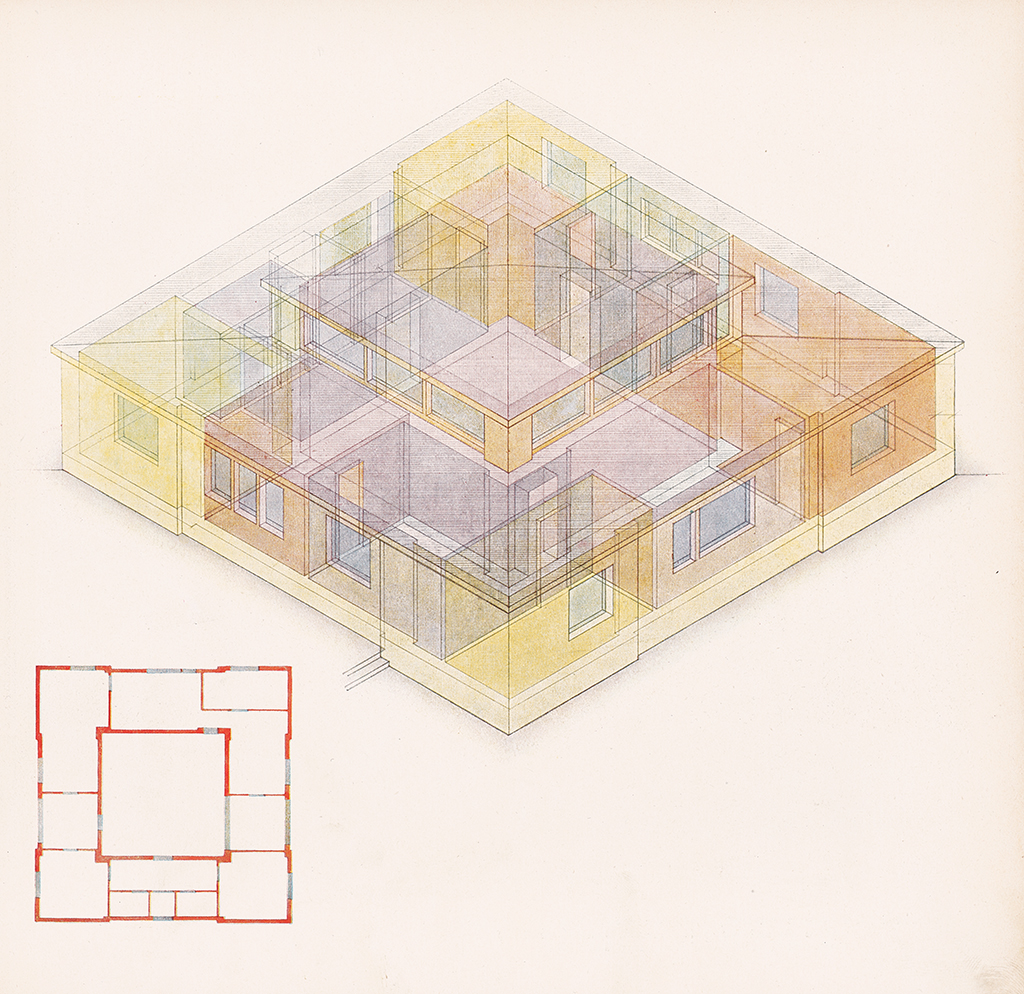

Haus Am Horn and the New Architecture

The competition for the design of an experimental house—the Haus Am Horn—represented a unique opportunity to highlight new directions in architecture at the Bauhaus. Turning away from expressionism, which had characterized the architectural work of the early Bauhaus, masters and students submitted entries based on rationalist and functionalist ideas. Georg Muche, then director of the weaving workshop, won the competition with a proposal for a

modest, utilitarian house that was intended to be industrially prefabricated. Untrained as an architect, Muche relied on Walter Gropius's partner Adolf Meyer for technical supervision of the project.

Realized later that year in collaboration with Bauhaus students and masters, Muche's design for Haus Am Horn centered on a living space lit by a band of clerestory windows and topped with a flat roof. The central living space was surrounded by interlocking rooms, eliminating the need for hallways. The stark modernity of the ensemble was enlivened by furniture and other design elements produced by students and masters in the workshops.

The Haus Am Horn exemplified the search for a dialogue between craft production and industrial reproducibility. As a result of the project, Weimar in this period became a site of architectural pilgrimage, marking the success of the initiative.

The images and digital media included on this website are made available for educational and scholarly use. Every effort has been made to contact the owners and photographers of objects reproduced here whose names do not appear in the captions. Anyone with further information concerning the photographers, artists, or copyright owners of these materials is asked to contact GRI Exhibitions so we may correct our records.