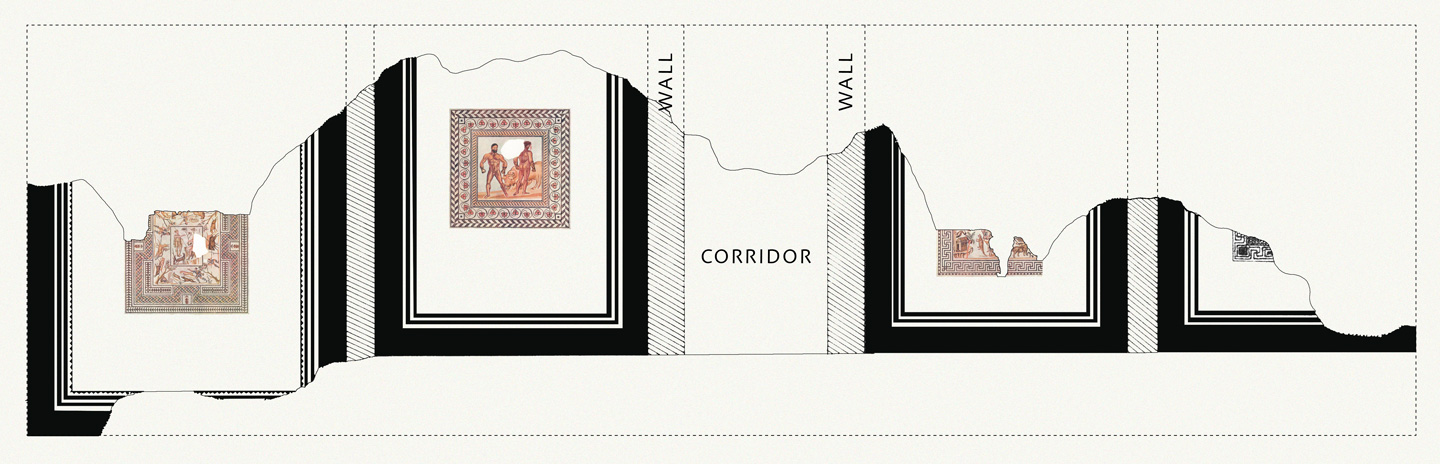

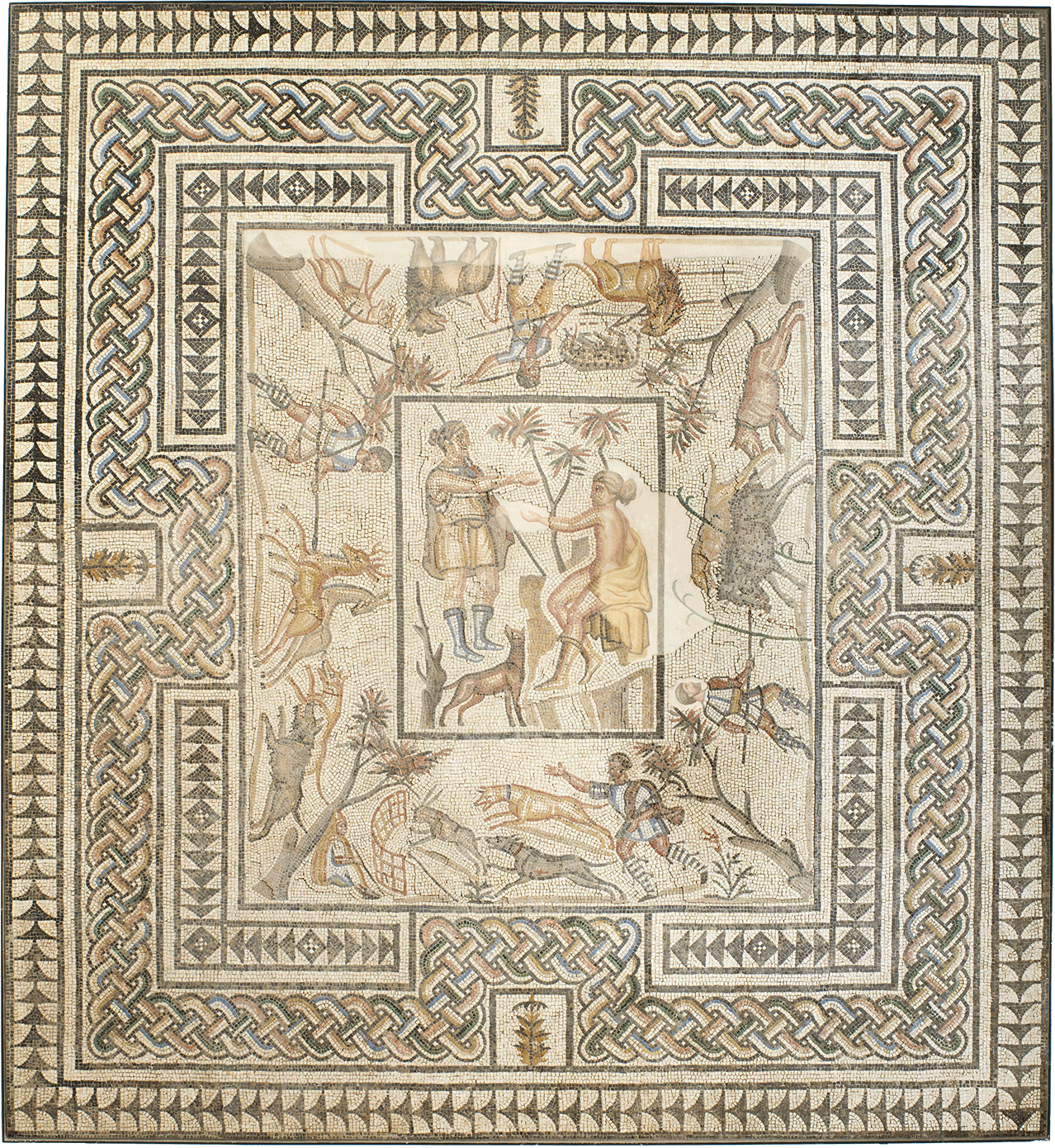

The modern history of the Gallo-Roman villa located near the town of Villelaure, twenty miles north of Aix-en-Provence (the Roman town of Aquae Sextiae), begins with its initial discovery in 1832 and spans more than 180 years. The villa, located in a district known as the Tuilière, which is bordered to the southeast by the Marderic River, was covered by an uncultivated field until the land was developed for sugar beet production in the 1830s.1 Four rooms with intact mosaic floors were uncovered in 1832, but they were reburied and not fully documented until their accidental rediscovery in 1898 and further investigation in 1900.2 The excavation unearthed four mosaics that paved a suite of adjacent rooms identified as the residential section of a wealthy private villa (fig. 12). According to the plan made by L.-H. Labande, the four adjacent rooms were oriented north–south (measuring a total length of 23.5 meters, with a width of 7 to 8 meters) and separated by a corridor 2.5 meters long with two rooms on either side.3 The mosaics of all four rooms had the same basic composition: a large central panel with a geometric border set on a plain white field, and, along the walls, a black border with alternating black-and-white lines. In the southernmost room (3.3 × 3.1 meters), only the badly damaged northwest corner of the pavement was preserved. The fragmentary remains included the black outer border and a corner of the geometric design that originally framed the central panel. This border was composed of a polychrome guilloche surrounded by a geometric design with small panels, possibly a meander pattern of swastikas and squares; a marine animal (possibly a fish or a dolphin) in one of the panels; and a rosette decorating the corner.4 The mosaic in the second room (7 × 4.6 meters), was also fragmentary, with only the lower portion of the central panel preserved, and it illustrated a Nilotic landscape (fig. 13).5 The preserved fragments depict, on the left, a temple perched on a cliff, a palm tree with dates, and an ibis. A crocodile is shown in the water, and, to its right, a pygmy stands on the bow of a boat, bearing an oval shield and brandishing a weapon at the crocodile. A second pygmy, also carrying a shield, stands in the center foreground. A hippopotamus appears on the far right, and, in the background, there is a cliff with the base of a building. An earlier description records images of horsemen and elephants that are no longer preserved.6 Labande reported that there was a fragment of marble revetment in situ in the southwest corner of the room. The corridor was unpaved at the time of the 1900 excavation.7 The Getty mosaic of Dares and Entellus (cat. 4) decorated the floor of the room (7 × 4.7 meters) on the opposite side of the corridor, and the north room (7 × 5.5 meters) contained the Diana and Callisto mosaic now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (fig. 14).8 The central panel of Diana and Callisto is surrounded by a rectangular frieze depicting different hunting scenes on each side and trees in the four corners: below, two hunters trap a hare in a net; on the sides, hunters attack deer and a wild boar; and above, a man with two spears fights beasts of the amphitheater.9 While all of the mosaics are dated to the late second century AD, the villa itself was occupied between the second and fifth centuries AD.

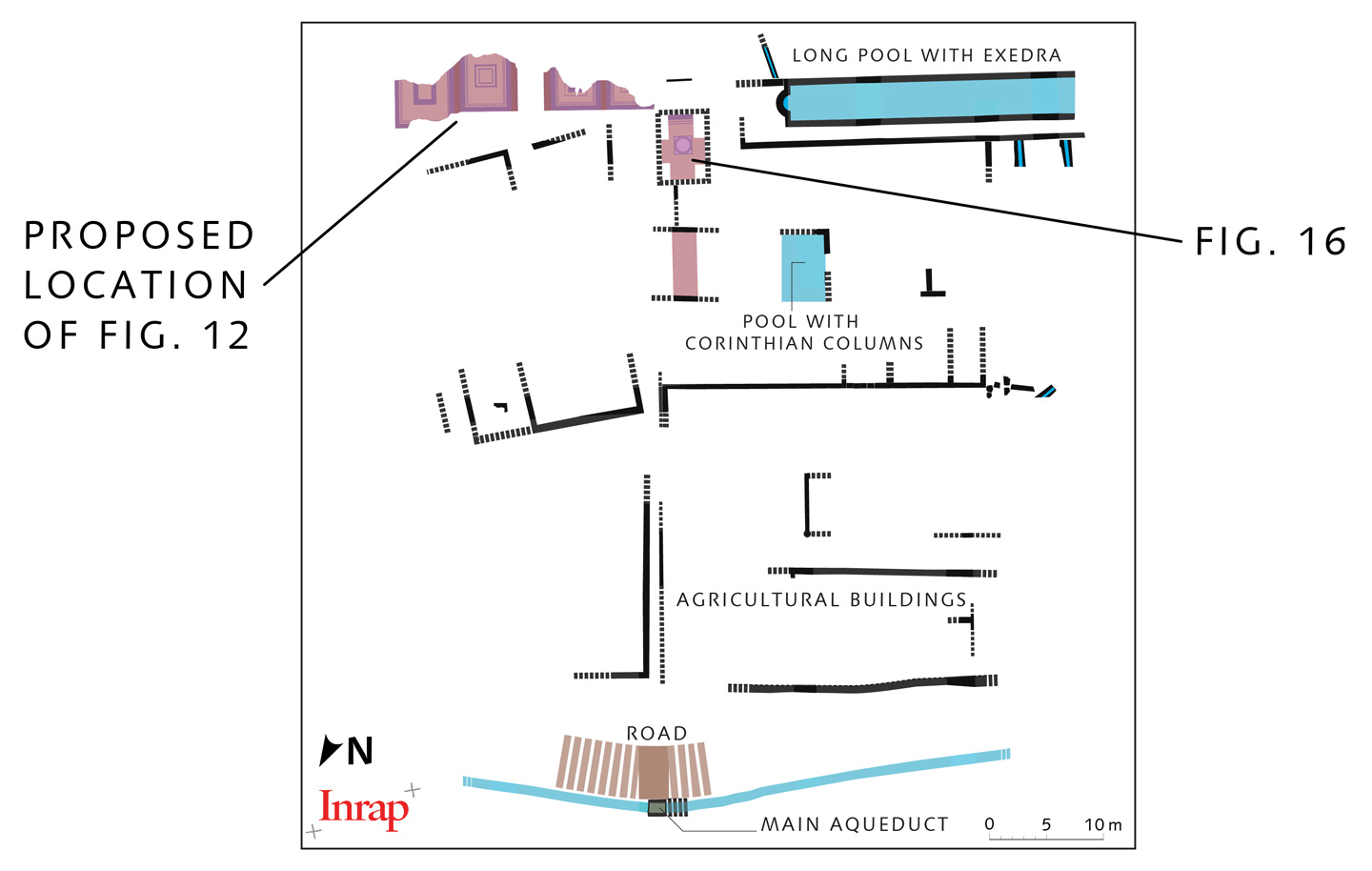

This exceptional site recently became the focus of a new project of investigation and preservation owing to the successful efforts of the community of Villelaure, located just southeast of the ancient villa.10 When the site was threatened by modern construction in 2006, the local villages, including Villelaure, Lauris, and Ansouis, intervened to preserve the area. The association of Villa Laurus en Luberon organized a diagnostic survey to assess the extent of the archaeological site. Subsequent excavations confirmed the existence of an extensive Gallo-Roman villa, and a proposal was made for its preservation in view of its great archaeological and historical value. Under the auspices of the Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (Inrap), Robert Gaday unearthed additional foundations of the villa, identifying both residential and agricultural areas (fig. 15).11

This type of villa, known as a villa rustica, or countryside villa, was often the center of a large agricultural estate composed of separate buildings to accommodate laborers, animals, and crops. At Villelaure, amenities of the main building included a peristyle court and a long pool with an exedra. The survey of the surrounding area revealed the existence of a water channel with an underground aqueduct, a ceramic kiln, and the remains of a necropolis. The excavations also uncovered a fifth mosaic decorating the floor of a rectangular room (5.7 × 3.8 meters). This fragmentary mosaic (fig. 16) preserves the lower part of a figure wearing shoes and a cloak, which was framed by a circular guilloche inscribed within a square. Notably, the recently discovered mosaic has the same format as the other four: a framed central figural scene (1.7 meters square) surrounded by a white field with a black-and-white border along the walls.

The 2006 excavations did not confirm the original location of the four previously excavated mosaics.12 At present, the focus remains on preserving the site from further modern damage, with the intention of carrying out additional excavations in the future.

-

For additional details on the discovery and later history of the mosaics at Villelaure, see cat. 4, in the present volume. ↩

-

For a discussion of the 1832 discovery, see Jacquème 1922, 101. The excavation report is published in Labande 1903, 3–13; and de Villefosse 1903, 13–14, 20–23. See also Lavagne 1977, 177–78; Lavagne 2000, nos. 913–16; and the detailed summary with bibliography in Tallah 2004, 374–75. ↩

-

A drawing of the floor plan is included in Labande 1903, 5, and reproduced in more detail in Lavagne 1977, 178, fig. 1, and Lavagne 2000, 307, fig. 48. ↩

-

The description is based on the report of L.-H. Labande; see Labande 1903, 6–7. According to Lafaye 1909, no. 102, the fragments of this mosaic were donated to the Académie de Vaucluse for the collection of the Musée Calvet d’Avignon, but they are now lost. See also Lavagne 2000, no. 913, plate C. ↩

-

Although this mosaic is now missing, it is known from watercolors made by the architect Henri Nodet prior to its disappearance and published in Lafaye 1909, no. 103; Labande 1903, plate 2; and Lavagne 2000, no. 914, plate C. ↩

-

Notice sur la terre de Villelaure et Janson exposée en vente à l’enchère publique devant le Tribunal de première instance séant à Apt., 1848, 15, cited in Lavagne 2000, 309. ↩

-

The 1903 report states that the pavement had “entirely disappeared” at the time of excavation and that there were no recorded documents of a paved floor; see Labande 1903, 7. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, nos. 104 (Dares and Entellus) and 105 (Diana and Callisto). The Diana and Callisto mosaic was displayed together with the Dares and Entellus mosaic at the exhibition Roman Mosaics across the Empire, held at the Getty Villa from March 30, 2016, to September 12, 2016. ↩

-

The wild beasts in the top scene possibly represent a lion, a bear, a panther, and a lioness; see Lavagne 2000, 313–15. ↩

-

Many thanks to our colleague André Girod and to the association of Villa Laurus en Luberon for all their assistance in gathering information about the history, both ancient and modern, of the site of Villelaure. In conjunction with these investigations, the association initiated a project to transform the nearby eighteenth-century Château-Verdet-Kleber in Villelaure into a museum and workshop for the study of mosaics. ↩

-

Gaday et al. 2006. ↩

-

According to the 2006 report, the north–south alignment of the four mosaics documented by Labande in 1903 does not correspond with the orientation of the fifth mosaic; see Gaday et al. 2006, 38. ↩