Much of the following information is drawn from the Annenberg/CPB Learner.org Biography of America Web site, which includes a wealth of material related to the historical era in which Lange worked.

Stock Market Crash and Great Depression

On October 24, 1929, the stock market crashed. Americans panicked as they saw their investments and jobs disappear. They experienced massive unemployment at a time when no federal programs existed to ward off starvation and homelessness. By 1933, one out of four workers was without a job, and the suicide rate soared as people gave in to despair.

|

||

People managed in different ways. The hard times drove masses from farms to cities, where they built shantytowns and sought relief at shelters and soup kitchens run by charities. Many men entered the "hobo jungle," hopping on freight trains to look for work and a bit of adventure wherever the trains stopped. If they were lucky, the train's brakeman turned a blind eye; if not, they risked getting thrown off or beaten. Numerous elderly people who had set aside enough money to live comfortably lost their savings and retirement incomes and joined various political "pension clubs" to support the creation of a set monthly income for retirees. By the end of the 1930s more than a million African Americans had left impoverished rural areas in the South to seek better prospects in northern cities. Viewed as competition for scarce jobs that "belonged" to whites, they suffered a renewed wave of racism, and few found the work they sought.

The Dust Bowl and the Westward Migration of Farm Workers

The combination of a period of terrible drought, soil erosion (caused by long-term mismanagement of the land), and unrelenting windstorms literally blew away thousands of farms in the Great Plains in the 1930s.

|

||

The blizzards of dust were so severe that they could entirely blacken the sky at noon. Without rainfall or topsoil, farmers found it impossible to grow any crops. The development of mechanized farming techniques, such as plowing with a tractor, further diminished the amount of work available to farm laborers. Many packed up their families and possessions and headed to California, lured by the prospect of working rich land in balmy conditions. What they encountered was far less enticing.

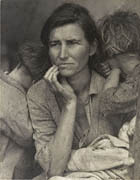

Hundreds of thousands of refugees arrived in California. There was such a glut of laborers that it was difficult to find work at all, and wages were severely depressed—so much so that quite a few migrants decided to return home, sometimes only to head west again later.

|

||

Longtime residents of California felt increasingly hostile toward the seemingly endless stream of bedraggled would-be laborers. Those workers who stayed were often housed in miserable little shacks and forced to sell their few belongings in order to feed themselves and their children. John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, based on firsthand interviews with migrant workers and published in 1939, is a moving fictional account of one family's experience as they travel west in search of a better life and joins the world of California's migrant agricultural labor force.

FDR and the Growth of Social Programs

Although President Franklin Delano Roosevelt came from a privileged background, his partial paralysis from a bout with polio allowed him to understand life's harsher realities. In his first inaugural address, given at the height of the Depression, he inspired some sixty million radio listeners with his optimistic words: "Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself." The nation was buoyed by the prospect of a chief executive who sympathized with the difficulties caused by the sharp economic decline.

|

||

In an effort to relieve suffering, FDR's administration launched a collection of social-justice experiments known as the New Deal. It included the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration), the Works Progress Administration (later the Work Projects Administration), and other programs that encompassed a wide range of goals.

Among its many achievements, the New Deal instituted federal deposit insurance for bank savings accounts, regulated the country's stock exchanges, reinvigorated the railroads, sent 500 million dollars in direct relief to the states, supported the arts, saved one-fifth of American homes and numerous farms from foreclosure, and helped to construct new airports, hospitals, and schools. Some criticized New Deal projects as "boondoggles," mere make-work tasks devised to keep the unemployed busy. FDR responded: "If we can boondoggle ourselves out of this depression, that word is going to be enshrined in the hearts of American people for years to come." The New Deal did not end the Depression, but did succeed in softening the worst of its effects. It was not until the entry of the United States into World War II, in 1941, that the Great Depression ended.

Relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II

Soon after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese hysteria spread throughout the government, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued

Executive Order 9066 in February 1942. This now-infamous edict caused more than 110,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast to be rounded up, tagged, and dispatched to internment camps for the duration of the war, on the suspicion that their loyalty might reside with Japan rather than with the U.S. Their land, businesses, and possessions were sold at a huge loss.

|

||

The experience was one of incredible grief and shame for those held in the ten barbed-wire compounds, which were cramped and demoralizing. Inmates, two-thirds of whom were American-born, could not help but notice that similar camps for all Americans of German or Italian descent had not been established (although some Italian Americans and German Americans were subject to detention, curfews, travel restrictions, and seizure of personal property). Those held captive protested their incarceration with strikes, riots, and petitions, but in 1944 the Supreme Court upheld its lawfulness as a matter of military necessity. In an effort to shield themselves and later generations from pain, many families of Japanese descent never discussed this humiliating episode after they were released in 1945.

By the end of World War II, the United States courts had found ten people guilty of spying for Japan. All of them were white. In 1987 Congress passed a law issuing an apology and authorizing a tax-free payment of $20,000 to each survivor of the camps.