1. Activate students' background knowledge by asking them to brainstorm everything they know about ancient Rome. If desired, display pictures of Roman monuments such as the Coliseum. Have students ever heard of ancient Rome? What do they know about it? Ask students if they have ever heard of Italy. What do they know about it? Explain that ancient Rome was a civilization in Europe about 2,000 years ago, and that this country is now called Italy. If desired, show students a map of Italy and point out the city of Rome. Then ask them to look at the illustration of the statue of the Mysterious Giant in the book. Is this a new statue or an old statue? (An old statue.) How do they know that it is old? (He is wearing a toga and Roman sandals. He is dirty and broken.) What do they think the Mysterious Giant is made from? (Marble or other stone). Why does he have his hand raised? (He may be speaking in front of a crowd or calling attention to an important point.)

Have students work in pairs to read the story The Mysterious Giant of Barletta. One student will read the first half of the story aloud and the other will read the second half aloud.

2. The Mysterious Giant of Barletta is an Italian folktale adapted and illustrated by Tomie DePaola. It is the story of a town in Italy, Barletta, and a statue that stood in front of the Church of San Sepolcro. The statue had been in the square as long as anyone could remember. Everyone in the town loved the statue and would greet it or play at its feet. Things change when the people of Barletta hear about an army coming their way to destroy the town. Everyone panics except for old Zia Concetta. Zia tells the statue that it can do something to save the town because of its size. Zia makes a plan to save the town. She asks for an onion and tells everyone to hide and not to ask questions. When the army comes marching into town, the Giant saves the town by crying and wailing that other boys won't let him play with him due to his size. The army becomes frightened and leaves the town. Barletta is saved!

Discuss the story by asking some of the following questions: What was life like in Barletta? What is the importance of the statue? What words describe Zia Concetta? Why does the Giant step down from his pedestal? How does Zia solve the problem of the invading army? What makes you say this? What is your evidence? What do the soldiers think of the people of Barletta? What do you think will happen to the Giant now that he has helped to save the town? How do you know? Tell students how ancient statues from the Roman Empire often wash up on the shores of Italy today.

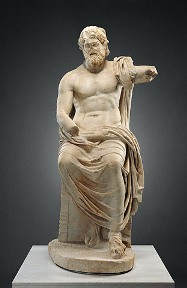

3. Look closely at the Statue of Jupiter. Ask students to find ways that this statue is similar to the Mysterious Giant (he is wearing a toga and Roman sandals, he is made of stone, and he is raising his arm.) Explain to students that Jupiter (called Zeus by the Greeks) was the king of gods. Ask students to explain how the artist made this figure look like a god. (He is sitting on a throne, he has a full beard, and he has a powerful body.) Explain to students that Jupiter's upheld arm once held a thunderbolt and that the sculpture is larger than life-size—the seated Jupiter is almost seven feet tall.

4. Discuss Poet as Orpheus with Two Sirens using the following questions: Who are these figures? What do you think they represent? Ask them to describe their poses, gestures, and facial expressions. Ask why students think the artist posed the figure(s) this way. What do the poses tell us about what the figures are doing and who they are? What does the clothing communicate about the figures? Have students demonstrate some of the poses to help facilitate the discussion and to encourage them to look more closely at the art.

5. Tell students they will create their own statue and bring it to life with their own story, just like the statue in the book. Model the creation of a paper statue for students. Using a pencil, draw the contour shape of a figure onto cardstock or railroad board. Begin with the head and work down to the neck, shoulders, chest, etc. until you finish with the feet. You can leave parts off, such as an arm or leg, in your demonstration to mimic some of the ancient statues. Next, use various lines to fill in the figure. Make sure to include a tunic or toga or other accessories, such as an animal. Then go over the pencil lines with a Sharpie.

6. Cut the drawing out and demonstrate how to make a gusset-style stand: From a corner of card stock, cut a right triangle (cut two sides of equal length, so the triangle has two 45-degree angles and one 90-degree angle, from the corner). Also cut a square of card stock about the same size as the triangle. Glue one of the short sides of the triangle to the leg of the statue, and the other side to the square piece of cardstock, which will rest flat on the ground. Hold until the glue sets and the statue will stand firmly.

7. Students create a statue in the manner you demonstrated. They then create a context for their statue. Explain to them that they will create a scene depicting an ancient ruin and including a landscape. Tell students, Imagine that you are the statue you created. If you were a statue, where would you want to stand—in a museum, in a meadow, in a busy city square, by the side of a road?

Demonstrate how to create a triorama. Take a 12 x 12 in. piece of drawing paper and fold it on the diagonal to make a triangle. Open the paper and fold it again on the other diagonal. You now have two folds in the paper that create an X. Cut one of the legs of the X from the corner of the paper, stopping at the center of the X. Overlap the sections next to the cut to make a shape that looks like a corner. Have the students draw a landscape on the three panels using colored pencils or crayons. After the landscapes are drawn, glue the overlapped pieces together.

8. Have students write a narrative story from the point of view of their statue. Remind students that the Mysterious Giant in the story has human qualities. Tell students, Imagine that you are the statue you created, standing in the landscape you just drew. How would you feel about the place you stood all day long? How would you feel standing all day, looking at the same thing, without moving? What things might you observe from where you stood? Who could you talk to? Describe some of the activities that might happen around you. Are you alone or surrounded by other people and things? If you are outside, what else is around you? What would it feel like during rainy weather if you were outside?

9. Have students create a storyboard or web to organize their ideas. Go through the writing process to help students write a narrative about their statue. After the stories have been revised and edited, students will publish (word process) their stories. These can be displayed next to their triorama and statue. |

|

|

|

| Marbury Hall Zeus, Roman, A.D. 1–100

|

|

|

|

Common Core Standards for English Language Arts

Grades 3–5

READING

3.2 Recount stories, including fables, folktales, and myths from diverse cultures; determine the central message, lesson, or moral and explain how it is conveyed through key details in the text.

3.5 Refer to parts of stories, dramas, and poems when writing or speaking about a text, using terms such as chapter, scene, and stanza; describe how each successive part builds on earlier sections.

3.6 Distinguish their own point of view from that of the narrator or those of the characters.

4.2 Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text; summarize the text.

4.5 Explain major differences between poems, drama, and prose, and refer to the structural elements of poems (e.g., verse, rhythm, meter) and drama (e.g., casts of characters, settings, descriptions, dialogue, stage directions) when writing or speaking about a text.

4.6 Compare and contrast the point of view from which different stories are narrated, including the difference between first- and third-person narrations.

5.2 Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text, including how characters in a story or drama respond to challenges or how the speaker in a poem reflects upon a topic; summarize the text.

5.5 Explain how a series of chapters, scenes, or stanzas fits together to provide the overall structure of a particular story, drama, or poem.

5.6 Describe how a narrator's or speaker's point of view influences how events are described.

SPEAKING AND LISTENING

3.1 Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 3 topics and texts, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly.

3.6 Speak in complete sentences when appropriate to task and situation in order to provide requested detail or clarification. (See grade 3 Language standards 1 and 3 for specific expectations.)

4.3 Identify the reasons and evidence a speaker or media source provides to support particular points.

4.6 Differentiate between contexts that call for formal English (e.g., presenting ideas) and situations where informal discourse is appropriate (e.g., small-group discussion); use formal English when appropriate to task and situation. (See grade 4 Language standards 1 and 3 for specific expectations.)

5.3 Summarize the points a speaker or media source makes and explain how each claim is supported by reasons and evidence, and identify and analyze any logical fallacies.

5.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, using formal English when appropriate to task and situation. (See grade 5 Language standards 1 and 3 for specific expectations.)

WRITING

3.4 With guidance and support from adults, produce writing in which the development and organization are appropriate to task and purpose.

4.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

4.4 Produce clear and coherent writing (including multiple-paragraph texts) in which the development and organization are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

5.10 Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Visual Arts Standards for California Public Schools

Grade 3

Connections, Relationships, Applications

5.2 Write a poem or story inspired by their own works of art.

Language Arts Standards for California Public Schools

Grade 3

Literary Response and Analysis

3.3 Determine what characters are like by what they say or do and by how the author or illustrator portrays them.

Writing Applications (Genres and Their Characteristics)

2.2 Write descriptions that use concrete sensory details to present and support unified impressions of people, places, things, or experiences. |

|

|

|