|

For hundreds of years, medieval manuscripts have been bought and sold, gifted and stolen, preserved and rearranged, loved and forgotten, hidden and displayed. They were cut into pieces, hung on walls, and glued into albums. They have survived wars, fires, floods, religious conflict, political tumult, the invention of printing, and changes in taste.

At times valued for their beauty, for their spiritual significance, or simply for the strength of their parchment pages, the books, leaves, and cuttings in this exhibition have been transformed again and again to suit the changing expectations of their various audiences and owners. By revealing the ways in which manuscripts have been repurposed both conceptually and physically, this exhibition explores their long and eventful history since the Middle Ages.

In this image, a male figure forms the letter I. His exact identity is unknown, but the presence of multiple instruments of torture identify him as a martyr. Notice the two large stones on his head, a sword through his neck, and a grill and fire at his feet. It was a common practice in the 19th century for collectors to trim away all traces of surrounding text in illuminated manuscripts, as here. Collectors mounted such cuttings into albums, allowing the viewer to concentrate solely on the imagery.

|

|

The provenance, or ownership history, of an object provides a record of the individual for whom the artwork was originally made. This might also include subsequent owners, when known. Evidence of ownership in manuscripts might include book plates, inscriptions, coats of arms, collectors' marks, or notes tucked between the pages. These enable a reconstruction of the many hands through which these books passed.

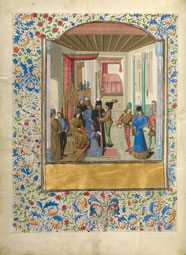

This image presents Vasco da Lucena, author of the French translation of the History of Alexander the Great, who kneels as he presents his masterpiece to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Charles was fascinated by the story of Alexander, epic hero and indomitable military leader of ancient Greece. His courtiers, also pictured here, flattered him by predicting that he was destined to become a conqueror as renowned as Alexander. This ornate copy of Vasco's text likely commissioned for a high-ranking official in Charles's court, originally featured the courtier's coat of arms at the bottom of the left-hand page. A later owner, however, erased the coat of arms, extended the margin designs, and painted over the gap, eliminating the earlier association once and for all.

|

|

|

|

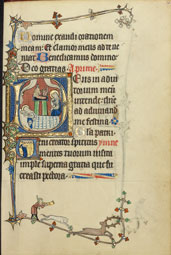

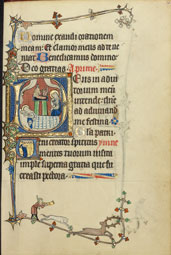

Initial D: The Nativity, from Ruskin Hours (text in Latin), unknown artist, Northern France, about 1300

|

|

|

|

The 19th century ushered in a widespread fascination with the Middle Ages. As a response to the cultural and social instability of the late 1700s and early 1800s, this bygone era came to be idealized for its unity, piety, romance, and chivalry. This renewed interest, sometimes called the Gothic Revival, led to the appreciation of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts as well as the creation of new ones. Some were honest reproductions, others forgeries that masqueraded as older works.

The Victorian art critic John Ruskin collected medieval manuscripts, including the one pictured here. His writings discuss how the inspired and intricate craftsmanship of the medieval artist was to be celebrated for its authenticity in contrast to the mass-produced objects of the modern age. Here, within the golden initial D, the Virgin Mary rests peacefully under the protective gaze of Joseph, while the Christ Child is attended by adoring animals. Ruskin copied this image and used it to illustrate Modern Painters.

|

|

As centuries passed, medieval manuscripts were sometimes refashioned to serve a different purpose. Cut from books whose liturgical or devotional use might have become outmoded, pictures were presented in a new format to fulfill a more current function. In the 19th century, collectors hung illuminated initials on the walls. These were no longer presented as letter forms beginning a word, but were instead valued for their aesthetic qualities.

At the center of this initial V, the apostles watch in wonder as Christ rises to heaven after his resurrection. The image was removed from a large choir book made for the Florentine monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, where the leaf's designer, Lorenzo Monaco, was also a monk.

|