The Renaissance Nude

The nude—the unclothed or partially clothed human body—has been featured in European art for millennia. After 1400, with the waning of the Middle Ages, artists depicted nudes as increasingly three-dimensional, vibrant, and lifelike— in short, more immediate and real. They employed diverse means: in Italy through a return to the models of ancient Greek and Roman art, and in northern Europe through refinements to the technique of painting in oils that enabled painters to capture textures—of flesh, of hair, of the sparkle in an eye—with unprecedented truth to nature. In concert with new scientific approaches, artists across Europe studied nature—including the human body—with increasing specificity and deliberation.

The meaningful depiction of the human form became the highest aspiration for artists, and their efforts often resulted in figures of notable sensuality. For Christians, however—who represented most of European society at the time—the nude body could be disturbing, arousing personal desire. Their conflicted responses are mirrored in our own body-obsessed era, filled with imagery of nudity.

The Renaissance Nude examines the developments that elevated the nude to a pivotal role in art making between 1400 and 1530. Organized thematically, the exhibition juxtaposes works in different media and from different regions of Europe to demonstrate that depictions of the nude expressed a range of formal ideals while also embodying a wide range of body types, physical conditions, and meanings.

Download the exhibition object checklist

CHRISTIANITY AND THE NUDE

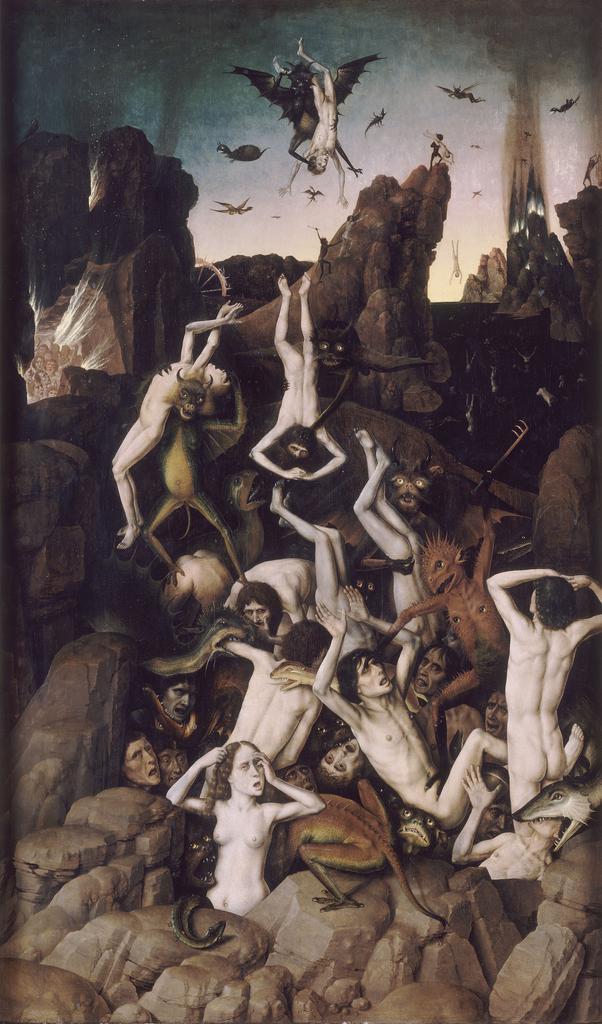

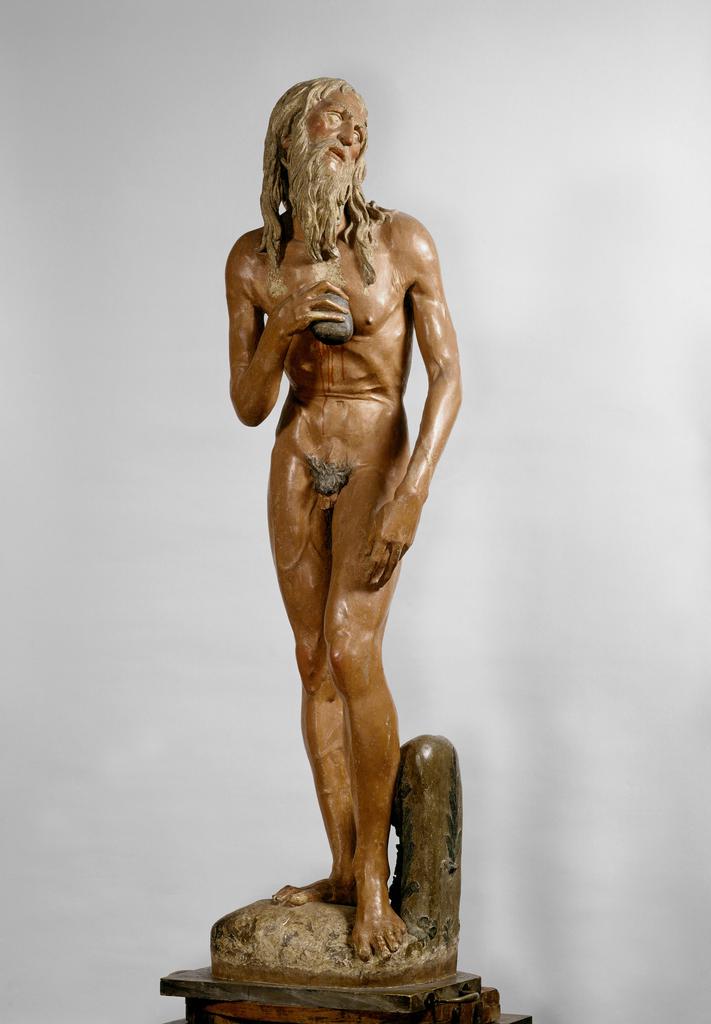

Renaissance Europe comprised a diverse body of countries and territories divided by language, modes of government, and local customs, but with the great majority of its populations sharing a Christian faith. In particular, the doctrines and rites of the Roman Catholic Church fostered common values and traditions throughout western and central Europe. Art played a key role in Catholic worship and instruction: on church walls and facades, on altars, and in liturgical and devotional books. Jesus Christ, the son of God and redeemer of humankind according to Christian belief, resides at the heart of its imagery; his body was shown as mostly unclothed, revealing the signs of his physical persecution and crucifixion. Similarly, imagery of the nude or mostly unclothed bodies of saints and of biblical heroes and heroines functioned in religious observance and private devotion, representing, at times graphically, their torture and martyrdom. Artists’ growing interest in the close study of nature, from plants and animals to human bodies, made the representation of Christian subjects more immediate and accessible, but also more palpable and sensual (and potentially discomfiting). Despite a rise in the depiction of secular subjects encouraged by a renewed interest in ancient Greek and Roman art, Christian subjects continued to dominate artistic production throughout the Renaissance.

HUMANISM: THE CLASSICAL REVIVAL

Just as it had in the Middle Ages, the Christian faith dominated art throughout the Renaissance. At the same time, the classical revival— beginning in Italy in the 1300s, in France a bit later, and by the 1500s elsewhere in Europe—fostered the influential intellectual movement known as humanism. Devoted to the recovery of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew texts, humanism applied classical modes of thinking to education, diplomacy, philosophy, and the writing of history and poetry— among the disciplines we call “the humanities” today. Humanists fostered the taste for the antique in the visual arts, stimulating interest in Greek and Roman mythology as well as literary subjects, inspiring artists to create some of their most original work. This section opens with works from centers of humanism that strongly impacted the emergence of the nude in the 1400s—Florence, Mantua, and Paris— while also exploring how humanism shaped art more fully across the Continent.

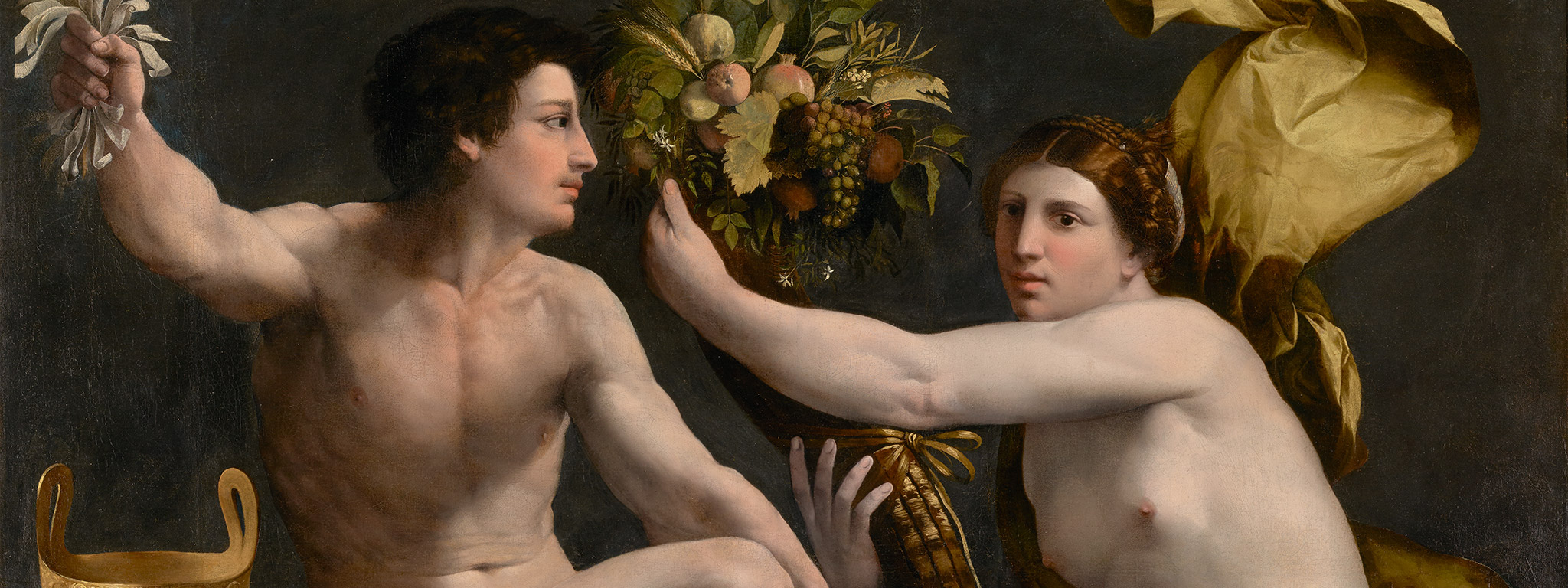

HUMANISM: EXPLORATIONS OF EROTICISM

The adventures of the Greek and Roman gods—with their stories of adultery and lust, drunkenness, debauchery, and deception— provided artists with opportunities to explore human impulses often condemned by the Christian Church. Within humanistic culture, much art created around the nude was erotic, exploring themes of seduction, the world of dreams, the sexual power of women, and even same-sex desire. Venus, the goddess of love, was a favorite subject of painters and sculptors. Thus, the sensual nude, which encouraged artists to push boundaries, could be controversial. Printmakers, practitioners of a new and essential medium for propagating erotic imagery, endured censorship from the Church, with some works that were considered obscene confiscated and destroyed.

BEYOND THE IDEAL NUDE

Idealized and beautifully proportioned bodies were not the only types of nudes in Renaissance art. Christian art often represented the bloodied figures of the persecuted Christ and saints, the bodies of the deceased and dying, and the emaciated anatomies of devout ascetics who express their faith through the denial of physical needs. By the fifteenth century, artists sought to underscore the visceral realities of death by crucifixion, scourging, and other tortures. Pious Christians derived meaning and, ultimately, comfort from engagement with the frank terms of Christ’s corporeal sacrifice. Artists also devoted attention to other abject bodies. Both the commitment to close observation and the rediscovery of ancient works such as the violent, emotionally charged Laocoön inspired the representation of complex psychological states. By the 1520s Italian artists such as Rosso Fiorentino and Pontormo, reacting to the idealized and heroic art of Raphael and Michelangelo, took inspiration from northern European artists who had long excelled at representing bodies in death, in decay, and outside conventional notions of beauty.

ARTISTIC THEORY AND PRACTICE

© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The revival of interest in Greek and Roman art—which was largely focused on the human body—helped transform workshop practice during the Renaissance. An increasingly systematic approach to the empirical study of nature also encouraged drawing from the nude model as a regular part of artistic training—in Tuscany by the 1470s, a few decades later in Germany, and in the Netherlands by the 1500s. Italian artists of the 1400s drew upon both surviving classical works depicting the human body and recently excavated sculptural masterpieces such as the Laocoön and the Apollo Belvedere. Meanwhile, renewed interest in such ancient texts as Vitruvius’s De architectura (On Architecture), which compared systems of architectural proportion with human ones, encouraged artists to explore the ideal proportions of the body.

Exemplifying the close link between art and science and the commitment to realistic observation, Italian artists such as Pollaiuolo and Leonardo da Vinci studied anatomy through dissection, seeking to understand the human skeleton along with the placement and character of muscle. Artists’ intense and repeated study from the nude model was intended to develop mastery of bodily structure, gesture, and pose, thereby facilitating the creation of convincing figural compositions. In northern Europe, such innovations were introduced to artistic training by leading masters, among them Albrecht Dürer and Hans Baldung.

PERSONALIZING THE NUDE

The broad appeal of the nude extended to the novel and personal ways Renaissance patrons sought to incorporate nude figures into the works of art they commissioned. For the interiors of their palaces, Italian humanist patrons sought elaborate decorative cycles, often on such mythological themes as “The Loves of the Gods,” in which the depicted hero’s erotic conquests stood for the patron’s notion of personal virility and his romantic aspirations. Commemorative bronze medals, featuring portraits on one side and allegorical nude figures on the other, offered another way for an artist to evoke the character and ideals of illustrious patrons. Further, just as humanist authors like Petrarch wrote in praise of their beloveds, aristocratic patrons sought flattering portrayals of their mistresses and other beauties, often seminude and in historical guises, creating a new genre, belle donne (“beautiful women”). An intriguing and unusual antecedent of this genre is Fouquet’s erotic portrayal of the French King Charles VII’s mistress with bared breast as the Virgin Mary.