|

|

|

Path in Woods, Great Spruce Head Island, Maine, 1981

© 1990 Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of the artist

|

|

American photographer Eliot Porter was among the first to successfully bridge the gap between photography as a fine art and its roots in science and technology. Porter promoted the use of color photography from the 1940s until the mid-1970s, a time when most serious photographers worked in black and white. Porter's work was widely published and used as a powerful visual argument for nature conservation. He explored new ways of presenting the natural world and his artistic and technical contributions to bird and landscape photography transformed these genres.

|

|

|

|

East Penobscot Bay, Maine, 1938

© 1990 Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of the artist

|

|

|

Eliot Porter was trained as a chemical engineer and a medical doctor. He began his photography career in the 1930s, making black-and-white photographs in his spare time while working as a bacteriologist and teacher at Harvard University. Photographer Alfred Stieglitz gave Porter a solo exhibition at his New York art gallery in 1938. The exhibition changed Porter's life. He decided to give up his academic post and devote himself to the art of photography.

The photograph above was included in the exhibition at Stieglitz's gallery. It is emblematic of the quiet beauty and strong sense of place in Porter's early black-and-white work.

|

|

|

The year after his exhibition at Stieglitz's gallery, Porter began using Kodachrome, a new color transparency film, and teaching himself the delicate, multi-step process for making color prints. For the next three decades he struggled against the notion that color photography was unsuitable for artists because it was "too literal." Porter actually used the color process to make highly expressive prints by slightly increasing the brilliance, contrast, or saturation in the transparencies. In 1964 Porter wrote that he hoped his color photographs would reveal "a new dimension in the perception and representation of nature in photography."

Between 1953 and 1984 Porter produced seven portfolios of nearly 8,000 prints. The image above from Porter's Iceland portfolio was published by the Sierra Club as a collector's edition.

|

|

|

In the early 1960s Porter began making photographic books with the Sierra Club, which played an important role in the conservation movement of the 1960s. The first book, In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World (1962), earned the Sierra Club an international reputation as a publisher of fine books.

The second book, The Place No One Knew, Glen Canyon on the Colorado (1963), was part of a campaign to stop construction of the Glen Canyon Dam. The vibrantly colored photographs of gulches, rock walls, and hidden canyons carved by the Colorado and San Juan Rivers did not prevent the dam from being built. However, it did result in federal review of all reclamation projects on western rivers and the passage of the Wilderness Act, which had been languishing in Congress since 1956.

|

|

|

|

|

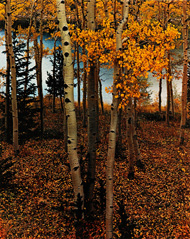

Aspens by Lake, Pike National Forest, Colorado, September 14, 1959

© 1990 Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of the artist

|

|

The public's positive response to the Sierra Club books showed Porter that he could use photography to make people aware of nature's beauty without compromising his artistic goals. With this realization, Porter was transformed from a passive, theoretical conservationist into an impassioned one.

Porter was elected to the board of directors of the Sierra Club in 1965, and served until 1971. In 1970 Porter wrote, "It has been said that wildness is a luxury, a commodity that man will be forced to dispense with as his occupancy of the earth approaches saturation. If this happens, he is finished. Wilderness must be preserved; it is a spiritual necessity."

|

|

|

|

Eastern Flicker (Colaptes auratus auratus), Great Spruce Head Island, Maine,

July 22, 1968

© 1990 Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of the artist

|

|

|

Porter began photographing birds as a boy. He returned to the subject later in life with the aim to "raise bird photography above the level of reportage, to transform it into an art."

To do so, he developed the first stop-action system for photographing birds. Porter used a tripod-mounted camera designed to hold sheets of film 4-x-5-inches in size. It was equipped with two powerful strobe lamps, synchronized to the shutter. The bright lights enabled him to use a high-speed shutter and the smallest lens aperture, which could stop the movement of small, swift birds and capture them and their immediate surroundings in sharp focus.

|

|

|

|

|

Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina), Great Spruce Head Island, Maine,

June 16, 1971

© 1990 Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of the artist

|

|

In 1941 Porter was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph various species of North American birds. Two years later, 54 of his bird photographs were featured in a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Porter's dream to share his bird pictures with a broad audience was realized in 1972 with the publication of Birds of North America: A Personal Selection. Containing 75 portraits of birds in their native environments, the book explains how Porter set new artistic standards for bird photography. Porter selected his favorite images from a 40-year archive covering 252 species. For the book's cover, he chose Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina), Great Spruce Head Island, Maine.

By the time of his death in 1990, Porter's archive contained more than 8,000 negatives and transparencies of North American birds.

The J. Paul Getty Museum is greatly indebted to the people who made this exhibition possible: the donors Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser and the lenders Janet Russek and Dan and Mary Solomon. Special thanks to our colleagues at the Amon Carter Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, for the loan of 34 prints from the Eliot Porter archive.

The exhibition is located at the Getty Center, Museum, West Pavilion.

|

|