|

|

|

Imaginary Landscape with Colonnades, Joseph Michael Gandy, 1812–1818

|

|

Greece is one of the most—and least—illustrated lands, at once a place of myth and a mythologized place. This exhibition presents maps and travel books, paintings, theatrical scenery, prints, and photographs, all of which created strong visual traditions for the ways that Greece, past and present, was depicted and understood. The works range from the late 1400s to the end of the 1800s, a period when ancient stories and their settings were rediscovered and became an essential part of European culture.

|

|

|

|

|

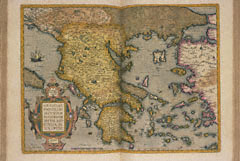

Map of Greece, in Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum (Antwerp, 1603)

|

|

Exploration of regions long visualized through Greek literature and art produced images

that are at once topographical and mythical. European trading ventures in the Mediterranean

depended upon accurate renderings of coasts and settled harbors. After the printing of Ptolemy's

Geographia in 1477, the eastern Mediterranean was an increasingly important feature of European

atlases. Correcting the errors of the Ptolemaic depictions of the Greek mainland, the author of

this book assembled both topographical studies and historical maps tracing fictional voyages such

as Jason's pursuit of the golden fleece.

|

|

|

|

The Sack of Troy, attributed to Tobias Bernhard, 1602–1612

|

|

|

Artists were inspired by stories of gods and heroes depicted in the epic and lyric poetry of Virgil, Ovid, and later Italian authors. In literature and art, interactions between the

natural and supernatural worlds were often interpreted as moral parables. The Trojan War inspired countless paintings of heroic deeds and battles. This miniature scene of the sack of Troy is true to the ancient texts. Greek ships anchor beneath a burning citadel, under attack by Greek soldiers who had hidden inside a wooden horse (upper right) presented to the Trojans. Outside the gate, Aeneas, abandoning his wife Creusa, leads his father and son to safety.

|

|

|

|

|

Landscape with Orpheus, Anonymous, about 1570

|

|

Landscape art evolved in this period as a new form in which nature conceals and reveals philosophical ideas about life and death, civilization and wilderness, and spirituality and sensuality.

In this painting, as the poet Orpheus charms the beasts and trees with his music, the territory

behind him opens in a sweeping panorama that encompasses both space and time. From the civilized world of music and cultivation in the foreground, the viewer's eye travels to an ancient land of ruins, and beyond to wild and uninhabited realms. The human figure is minimized, while attention to varieties of terrain, flora, and fauna dominate.

|

|

|

|

Landscape with Orpheus and Eurydice, Etienne Baudet (after Nicolas Poussin), late 1700s–early 1800s

|

|

|

Heroic landscapes by Poussin elevate the human condition by combining dramatic themes, stately architecture, and the grandeur of nature. The wedding of Orpheus and Eurydice, who

will perish shortly afterwards from a snakebite, takes place here against the background of

Roman monuments. Although the landscape is composed as an ideal, it harbors enigmatic and

threatening omens. The burning fortress and boatman (ferrying the dead to Hades?) are allegorical

allusions to the ill-fated couple and perhaps to disorder in contemporary politics.

|

|

|

|

|

Vue du Temple de Minerve-Suniade, in Jean-Baptiste Lechevalier's Voyage de la Troade, fait dans les années 1785 et 1786, 1802

|

|

From the late 1700s, Greece and the islands were more easily accessible for Europeans who set out to explore the actual settings of legend and myth. Lechevalier journeyed through Greece en route to historic investigations of the Trojan plain. At Sounion, he depicted this classical colonnade, now identified as the Temple of Poseidon, perched on a promontory.

Inherited expectations, as well as visual and verbal conventions for representing classical

mythology, strongly shaped representations of Greek landscape produced by artists, architects,

and topographers. The result is a mixture of fact and fiction in illustrations that blur distinctions between truth and desire.

|

|

|

|

Corinthe, L'Acropole, Braun, Clément et Cie., 1880s

|

|

|

In the late 1800s, photography offered firsthand documentation of fabled monuments in their actual physical surroundings. In contrast to the idealized environments represented in preceding

centuries, the camera did not reveal picturesquely overgrown ruins, but rather stark, elemental landscapes. Isolated temples pose timelessly as geometric abstractions set against an untamed terrain.

Doric temples like this one at Corinth are monumental reminders of the mythological

associations permeating Greece. The documentary quality of photographs hints that historical

episodes stand behind the mythical stories.

|

|