|

Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884) is known as the most important French photographer of the nineteenth century because of his technical innovations in the still new medium of photography, his role as the teacher of other noted photographers, and the extraordinary imagination he brought to picture making.

In this exhibition, explore Le Gray's extraordinary career through more than 100 rare photographs made from the 1850s until 1867.

This exhibition is selected from a survey of Le Gray's work created by and shown at the Bibliothéque nationale de France, Paris, in the spring of 2002. It is the largest exhibition ever held in the United States of his work.

|

|

|

Heavy industry was rarely a photographic subject in the 1850s, so this atmospheric study of a factory is highly unusual. The area around Terre-Noire (literally, black earth) in central France is rich in coal and iron ore, the two essential elements for the fabrication of iron and steel. The blackened foreground and spreading clouds of smoke that veil the deforested hillsides create a bleak and powerful image of the effects of early industrialization.

|

|

|

|

Large Wave, Mediterranean Sea

|

|

|

|

|

|

Because of the limitations of photographic materials at the time, it was extremely difficult to capture both sea and sky in a single image. By combining two negatives—one for the foreground water and another for the clouds—Le Gray triumphed. This use of combination printing was not criticized when he exhibited his seascapes, although it is unlikely that he hung finished images utilizing the same negative for the sky in each adjacent to one other, so perhaps it went undetected. More important was the harmonious union produced by his innovative technique, which he originally invented for landscapes with overexposed skies.

|

|

|

During the 1850s, Le Gray made several trips into the forest of Fontainebleau, an old royal hunting preserve that had been turned into a public park and a popular weekend destination from Paris. A school of landscape painters there were named for the village of Barbizon in the forest. In this photograph, the camera is low and close to the beech tree, emphasizing bark texture and filigreed foliage. No effort was made to show its overall shape, and its surroundings are out of focus. Attention is concentrated on the dramatic torsion of the twisting trunk and roots, which makes the tree almost appear to be in motion. Le Gray’s studies of trees in the landscape link him to Barbizon painters Théodore Rousseau, Narcisse Diaz, and their predecessor Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.

|

|

|

In 1857, Emperor Napoleon III commissioned Le Gray to document the inauguration of a summer training camp for the army at Châlons. The photographs were intended to celebrate French military might and to be included in albums to be given to the generals. Le Gray kept his distance from maneuvering soldiers in order not to get in their way and to prevent dust from disfiguring the damp plate he inserted into his camera just before exposure. To emphasize and isolate the silhouettes of the men on horseback, he apparently asked two soldiers near them to lie down.

|

|

|

The variety of images Le Gray produced at Châlons testifies to his adaptability and imagination. The Zouaves, whose colorful uniforms and white turbans derived from their North African origins, were known for bravery and gusto as well as high-spirited theatrical skits. Knowing that the emperor, like their fellow soldiers, was entertained by their antics, Le Gray photographed this popular regiment more often than any other. While the storyteller held a dramatic pose for a few seconds, Le Gray recorded his circle of listeners.

|

|

|

|

Mollien Pavilion, the Louvre

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1859, Le Gray was famous, but the portrait studio he had set up with borrowed money, and then neglected, was bankrupt. Perhaps in an effort to satisfy his creditors, he made a series of pictures of Paris that glorify the city as no one else had done. In this composition, he waited until the striking shadow that falls across the middle third of the picture brought forward this heavily ornamented, newly constructed pavilion of the palace of the Louvre. The lines of the paving stones also lead the eye toward the pavilion. The exuberant architecture reflects the prosperity of France under Napoléon III. The detail visible in the deep shadow is an indication of his mastery of the medium.

|

|

|

|

|

Portrait of Giuseppe Garibaldi

|

|

Possibly to escape his financial woes, Le Gray accepted the invitation of novelist Alexandre Dumas to photograph sites they would visit during an extended sailing trip on the Mediterranean. When Dumas and Le Gray arrived in Sicily in 1860, the great revolutionary Garibaldi was in the midst of liberating it from Bourbon rule. Garibaldi opposed its repressive and barely competent kings in favor of the developing kingdom of Italy, which was ruled by a more liberal, northern monarchy. The red-bearded Garibaldi made his red shirt a symbol of revolution. Here he poses confidently for the camera, which he regards with forthright curiosity. This portrait was frequently reproduced in the form of an engraving, thus publicizing his enterprise.

|

|

|

|

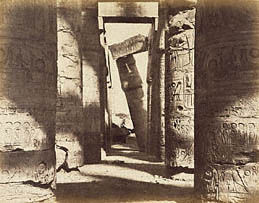

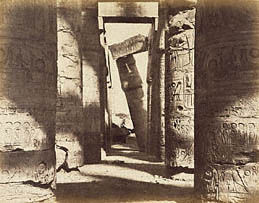

Hypostyle Hall, Temple of Amun, Karnak

|

|

|

Abandoned by Alexandre Dumas on the island of Malta, Le Gray went first to Lebanon and then to Egypt, where he settled. This displaced colossal column of the great hall of the temple of Amun, the Egyptian sun god, was a favorite subject for nineteenth-century photographers, but none produced a view as dramatic as Le Gray’s. He waited until light slashed diagonally across the principal axis of the temple, creating a bold, painterly composition of light and shadow. No person is visible to indicate scale, but the columns are forty-five feet tall.

|

|