|

This exhibition features images of Christ in illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The images show the multiple ways in which Christ was understood: as the son of God and as God, as human and divine, as the sacrifice made for mankind, and as the divine judge who would save or condemn humanity at the end of time.

The images in the exhibition, primarily from western European manuscripts, demonstrate how medieval and Renaissance faithful sought to participate in Christ's suffering and salvation through art and prayer.

The wounds Christ suffered on the cross were considered to express the essence of his humanity. This image from the Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg accompanies a prayer dedicated to the wounds of Christ, which the artist depicted as disembodied hands, feet, and a side wound (seen here as a heart).

|

|

|

The high point of the Catholic mass was, and still is, transubstantiation—the ritual transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, which invokes his presence on the altar. The participants in the mass then consume the bread and wine, receiving Christ's divine grace.

One of the central beliefs about transubstantiation was that Christ was not symbolically but truly present on the altar. The vision of Saint Gregory became a popular subject in later medieval art as an affirmation of the mystical nature of transubstantiation.

A bloodied and gaunt Christ, surrounded by the instruments of his torture and raising his hands to display his wounds, appears as a vision before the 6th-century pope Gregory the Great. Gregory experienced this vision after becoming aware that an individual in the church doubted the real presence of Christ in the host, the bread that is transformed into the body of Christ during the mass.

|

|

|

The enthroned Christ in majesty was immediately recognizable to medieval viewers as the divine judge who would come again at the end of time. Here he is surrounded by the four beasts of the Apocalypse, which were also understood as symbols of the four authors of the Gospels.

This leaf was once part of a missal, where it preceded a text for prayers to be said during the canon of the mass, when the bread was ritually transformed. The chalice in Christ's left hand and the Eucharistic bread hovering above it reminded viewers both of Christ's sacrifice and of their own need to participate in the ritual of Communion (partaking of the consecrated bread and wine during the mass) as a means to salvation.

|

|

|

|

Christ in Majesty, French, 1188

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In medieval and Renaissance churches, gilded metal-relief sculptures of Christ and sculpted metal book covers gave physical form to the logos (word of God). These highly symbolic works of art reinforced the ways in which Christ was made present through church services.

This figure was one of a larger group that likely covered the front of an altar in the Cathedral of Saint Martin in Ourense, Spain. An entire altar decorated with similar figures and surrounded by flickering lamps emitted a golden glow in the church, bringing to mind Christ's words from the Gospel of John, "He who sees me, sees Him who sent me. I have come as a light into the world."

|

|

|

|

|

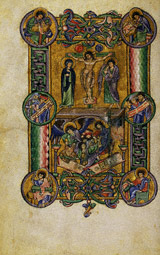

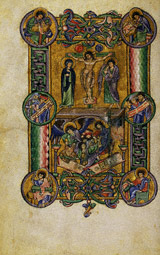

The Crucifixion and the Harrowing of Hell in a New Testament, Italian, late 1100s

|

|

|

|

|

|

In representing the son of God, medieval and Renaissance artists gave tangible form to divinity. Christ was understood to be not only the son of God, but the second person of the Trinity—the coexistence within God of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Images of Christ's crucifixion and resurrection served as visible signs of his supernatural power over sickness and death. The image on the top half of this page depicts Christ's death on the cross, through which he absolved the sins of humanity. The image at bottom depicts the events that occurred on the Saturday before Christ's resurrection on Easter Sunday, as described in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. Christ descended to Hades, where he rescued the Old Testament individuals who died before his sacrifice made their salvation possible. Christ stands on the broken doors of Hades, holding a cross staff and banner. He grasps the wrist of the gray-haired Adam, whom he pulls from his prison.

The combined representation of the Crucifixion with the harrowing of Hell allowed the medieval viewer to simultaneously experience Christ's human sacrifice and his triumph over death.

|

|

|

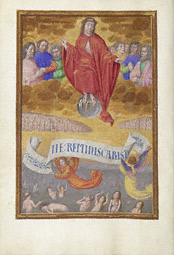

Depictions of the enthroned Christ, such as this image from the Spinola Hours, reminded the viewer that Christ would return to earth at the end of time to judge humankind. According to the Gospel of Matthew, Christ would divide the saved and the damned into two groups, "as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats." Christ, the divine judge, here displays his wounds to all humanity, which is shown gathered beneath him.

The image appears in the book at the beginning of the section containing the penitential psalms. This was a standard section in the book of hours, a collection of private prayers to be said throughout the day. The words "Ne reminscaris D[omine]" on the banner held by the angels below are the opening words to the response recited before the seven penitential psalms: "Remember not our Lord, our or our parents' offences: neither take vengeance for our sins."

|

|

|

Medieval viewers cultivated an emotional connection with the human Christ through an intense focus on his humanity and suffering. While early medieval images often emphasized Christ's triumph over death, later images directed new attention to themes such as Christ's childhood and his suffering, encouraging viewers' identification and imitation.

This illumination is one of 51 images depicting Christ's life in a 12th-century English Vita Christi (Life of Christ). In what was perhaps an effort to emphasize the humanity of Christ, the manuscript contains several images of the adolescent Christ in the years before his ministry. In this rarely depicted scene, the 12-year-old Jesus is taken to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover. The Latin text at the bottom of the page serves as a descriptive caption, and was added in the 15th century to identify the scene.

The Vita Christi may have served as a devotional picture book (with no text) or perhaps as a pictorial preface to a psalter, a manuscript containing the book of Psalms and other devotional material. In the 15th century the book was expanded; 57 miniatures and devotional texts were added.

|

|

|

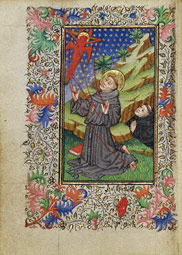

In addition to Christ, the medieval faithful also venerated saints such as Francis of Assisi, who was said to have received the marks of Christ's wounds on his own body as a sign of his sanctity. In emulation of Christ's exile in the desert, Francis retreated to the wilderness for 40 days of prayer and fasting. There, an angel appeared to him, and Francis received the stigmata (the marks of Christ's wounds from the cross) as a mark of his own holy status. Here the angel appears as a crucified figure hanging on a cross in the sky above.

The image comes from a book of hours, a private devotional book used by Christians to focus their private meditations on Christ's life, his teachings, and (in particular) his suffering.

|

|