Making ART Concrete

Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros

After World War II, avant-garde artists in Argentina and Brazil began to question the role of art in society. Intent on creating a new type of object, they rejected long-established traditions in painting—including all forms of representation— and pursued the possibilities of geometric abstraction. They aimed to create artwork so precise in conception and execution that it formed its own material, or “concrete,” reality.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, development programs in both countries spurred new industries and manufacturing techniques. In this context, Concrete artists (as they became known) began to experiment with novel formats, shapes constructions, and materials, including paint and supports intended for household or commercial use. They envisioned their art as a part of everyday life, which they hoped would be transformed according to Marxist principles.

Making Art Concrete presents the first comprehensive technical study of these works, combining art historical and scientific analysis to reveal the material choices and working methods of Concrete artists. The exhibition is a collaboration between the Getty Conservation Institute, the Getty Research Institute, and the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, a world-renowned collection of Latin American art.

Breaking the Frame

View of painting with canvas edge painted blue and yellow.

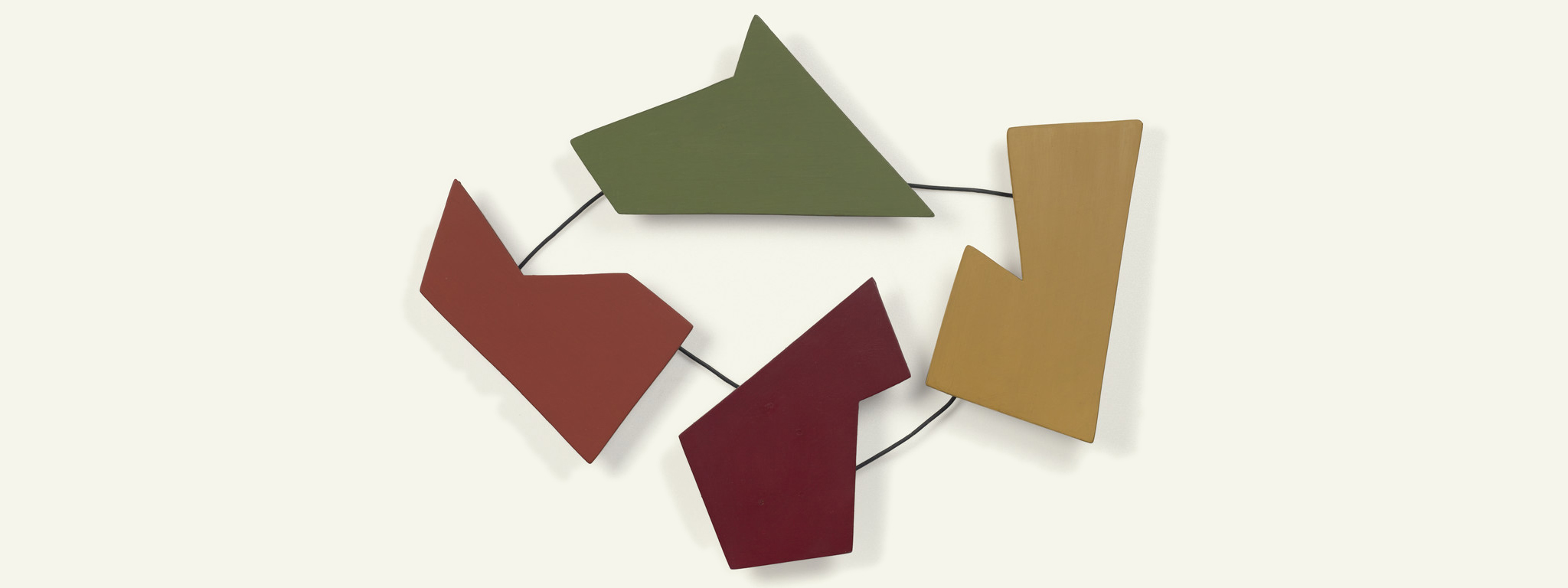

Concrete artists in Buenos Aires rejected the rectangular frame as an artificial dividing line between a painting and its surroundings. In 1944, Uruguayan painter Rhod Rothfuss argued that artists should determine the shape of a composition according to the forms within it. The resulting structure became known as a marco recortado (irregular cut-out frame). As a further evolution of this approach, artists developed the “coplanar,” in which individual painted elements occupy a single plane parallel to the wall or support.

Constructing Concrete Reality

Artists in Buenos Aires initially cut their marcos recortados from fragile cardboard sheets similar to the paperboard that Rothfuss used for his Cuadrilongo amarillo. They soon came to prefer sturdier, inexpensive hardboard panels made from heat-compressed wood fibers. The smooth surfaces of these boards made them particularly popular with Concrete artists in Brazil, who sought to minimize visible brushwork and to emphasize the physical presence of their works in space.

Concrete artists from Brazil also rejected traditional frames. In São Paulo, some heightened the three-dimensionality of their works through the use of deep hanging devices, which push the picture plane toward the viewer. The concept of the não-objeto (non-object), introduced by Brazilian poet and theorist Ferreira Gullar in 1959, provided a critical frame- work for Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, who dispensed with frames and pedestals in favor of folds and pockets that engage the viewer in spatial-temporal relationships. Willys de Castro investigated similar themes in his objetos ativos, which play with visual and spatial illusions that are enhanced by the movement of an onlooker’s body.

Looking Through Paint Layers

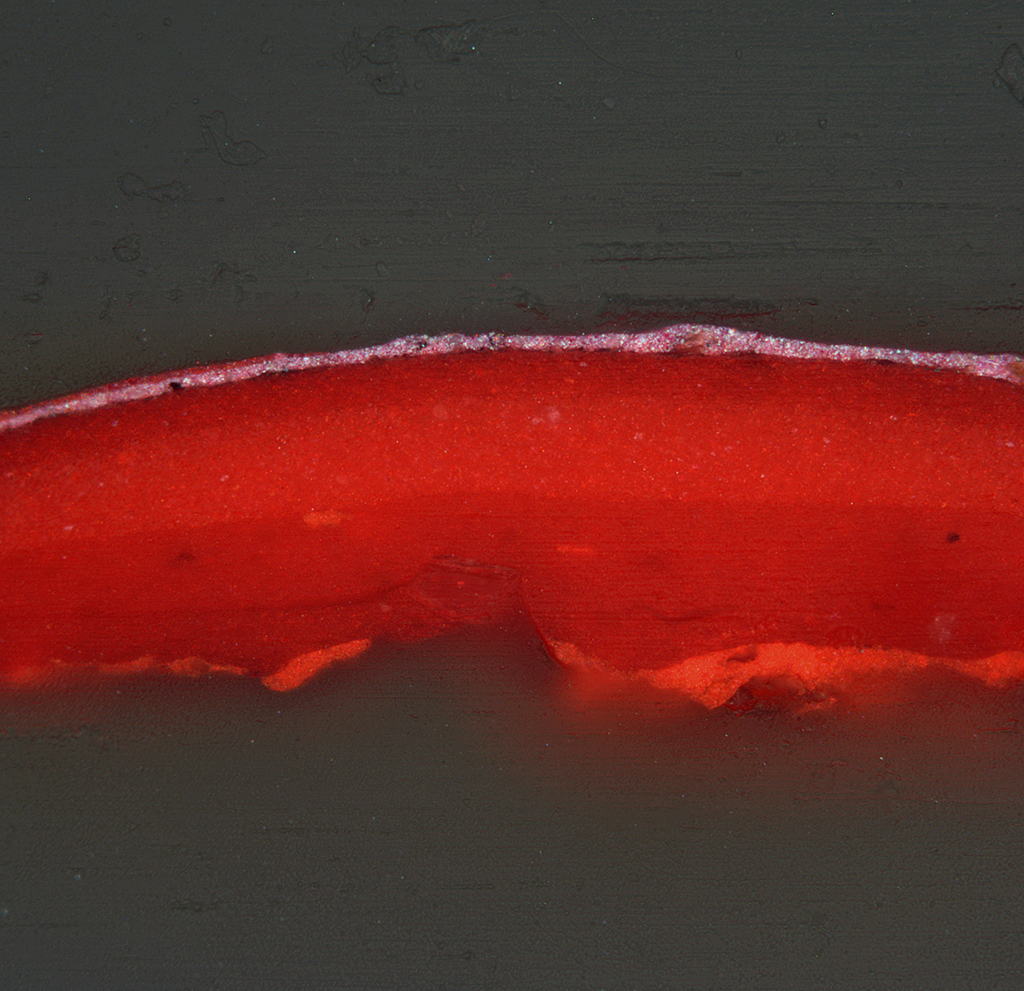

This cross section of a paint layer shows that Lozza radically changed the work's color scheme over time. As seen in this sample, the composition was initially red, before the now-visible green paint was applied over the top.

One way to understand how a painting was constructed is to examine microscopic samples of its layers in cross section. A fragment containing multiple paint layers is embedded in clear resin, turned on its side, and sanded to a smooth finish. This process reveals the order in which an artist applied layers of paint; the kinds of pigments and fillers that were used; and how the paint was mixed (by hand or industrially) and applied (by brush or spray). In some cases, the layer structure is quite straightforward. In others, cross sections reveal earlier states of a work and demonstrate the complexities of an artist’s material processes and decision making.

Between the Handmade and the Industrial

Fiaminghi applied two types of housepaint by brush to create very different gloss levels (which are most apparent when viewed with a reflecting light).

Paints and Paint Surfaces

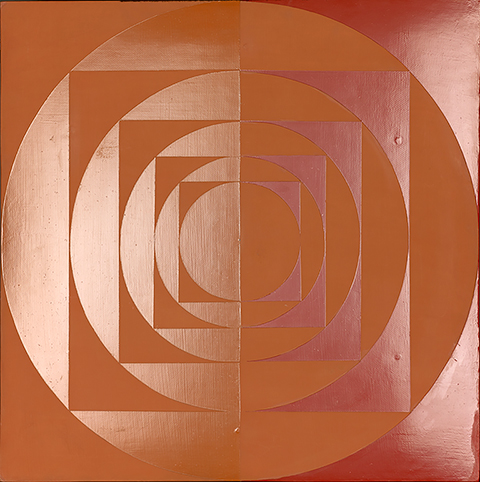

After conducting the support for a new work, Concrete artists selected paint types and application techniques from a wide array of traditional and industrial materials and tools. The combination of these factors determined whether a work looks more like a traditional handcrafted easel painting or an industrially produced object. In all cases, however, the artists applied and manipulated paint by hand.

While most Concrete artists in Argentina used traditional tube oil paints through the 1940s and ‘50s, analysis reveals that many artists in Brazil in the 1950’s took advantage of the fast-drying and self-leveling properties of industrial paints. These paints allowed them to create highly finished surfaces essentially free of the “subjective” traces of the Furthermore, custom-made paints have been identified in the works by Geraldo de Barros and Aluísio Carvão.

The final textures of these works also depended on the methods of paint application. Willys de Castro and Hermelindo Fiaminghi used traditional brushes to make subtle impasto. Geraldo de Barros combined brushed and sprayed sections into a single flat surface. Some works by Judith Lauand display a mottled layer of housepaint, which was probably applied with a roller.

Painting Straight Edges

Our perception of whether Concrete works look “handmade” or “industrial” is also determined by the techniques artists used to paint straight edges. Though geometric compositions may seem easy to achieve, artists created clean lines and mono-chromatic forms through attention to the smallest details. Their techniques included using a brush to paint edges freehand; a brush or ruling pen in combination with a straightedge; or self-adhesive tape.

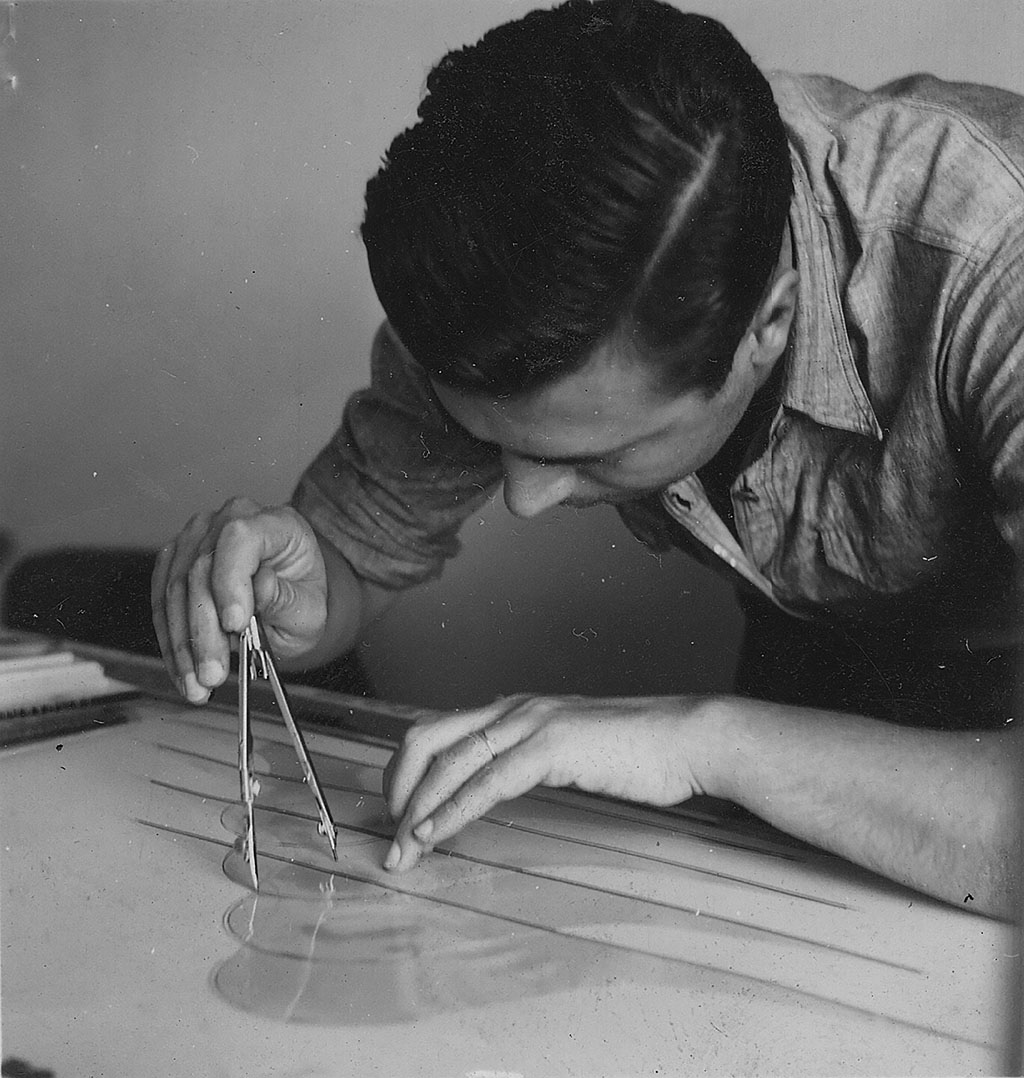

Ruling Pen

Both Alfredo Hlito and Waldemar Cordeiro relied on a ruling pen to outline the forms in their compositions with paint. Applying viscous paint with this tool—which was originally designed for architects and designers to use with free-flowing ink—required considerable skill.

The two metal tips of these pens hold a limited amount of liquid through capillary action. The artists had to create lines section by section; they then filled the spaces between them with a brush and additional paint.

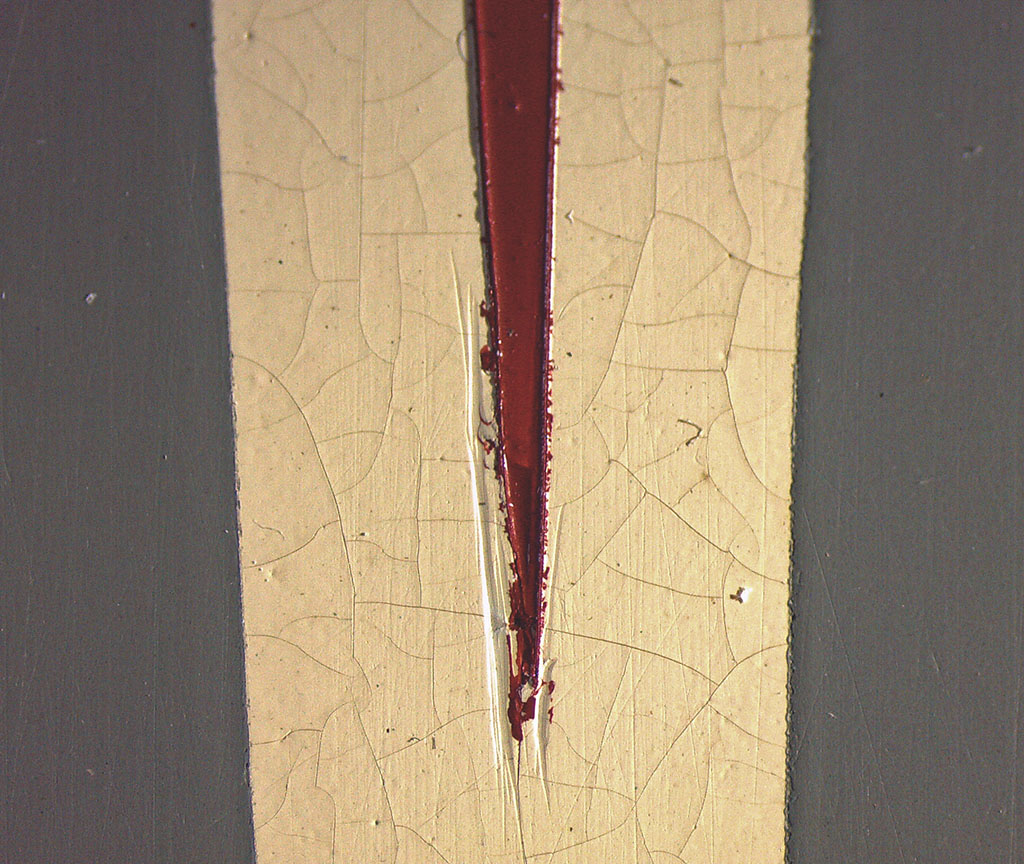

This photomicrographic details shows the incised lines and paint bleed associated with the use of self-adhesive tape.

Self-Adhesive Tape

The invention of self-adhesive tape in the United States in the mid-1930s allowed artists to paint sharp edges with much greater precision. The sharp ridge of paint created by transparent cellophane tape catches the light differently than do the rounder edges left by a ruling pen.

In Brazil, Grupo Ruptura artists used tape to create highly concise compositions that reflect their interest in Gestalt principles of perception (such as upsetting the visual distinction between figure and ground).

In Search of the Concrete in Painting, Poetry, and Design

Seeking to infuse everyday life with Concrete principles, artists in Argentina and Brazil worked to create an interdisciplinary movement encompassing poetry, theater, music, dance, architecture, and urban and industrial design.

In the mid-1940s, artists in Argentina began to define their own approach to abstraction. They initially focused on the “Concrete” in painting and poetry, and they incorporated other artistic genres over subsequent years. In Brazil, Concrete artists and poets developed a shared, coherent agenda, even exhibiting together in the mid-1950s. Artists in both countries became interested in industrial design, with some establishing their own furniture or commercial design companies. This gallery considers Concrete art's first two decades, largely through artists’ published materials.

Diverging Groups and Debates

By 1945 the artists affiliated with Arturo set up two rival initiatives, Movimiento Madí and Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención (AACI), both of which laid claim to the marco recortado (irregular cut-out frame). However, by 1947 members of the AACI considered the marco recortado exhausted, and they returned to traditional rectangular formats.

Both groups embraced interdisciplinarity. The Madí artists' initiatives, as documented in their magazine Arte Madí universal, included enlisting composer Esteban Eitler to perform “Madí music” and dancers to perform silent “movements in space.” AACI artists Tomáás Maldonado and Alfredo Hlito focused on industrial design, typography, and architecture, disseminating their ideas through their magazine, Nueva visión (New Vision).

Poetry and Design

Poetry was a vital source of inspiration and dialogue for Concrete artists. In Brazil, the São Paulo-based Noigandres poets—brothers Augusto and Haroldo de Campos, and Décio Pignatari—developed a form of poetry that intersected with design, focusing on the appearance of words in graphic space, the material qualities of language and text, and the sonic aspects of language. In 1956 and 1957, they exhibited their “poster poems” alongside Concrete artists' works.

Max Bill, a Swiss Concrete artist, was an important figure for artists in Argentina and Brazil. His exhibitions in Brazil in the early 1950s had a singular impact on Concrete artists. Shortly after cofounding the influential Ulm School of Design in 1953, Bill invited Tomás Maldonado to teach there.