|

This exhibition spotlights one of the most unusual objects in the Getty Museum's collection—a 12-foot-long transparent drawing by Louis de Carmontelle. Depicting elegant figures in a sun-drenched landscape, it was meant to be unrolled in front of viewers, section by section, through a backlit viewing box. It is thought to be the first of Carmontelle's rouleaux transparents ("rolled-up, transparent drawings"). Viewed in a darkened room, with accompanying live storytelling, this invention gave viewers the experience of taking a lively journey through a sunny landscape. Much as today's moviegoers, Carmontelle's audience became mesmerized by the images and stories that unfolded as they watched.

The full drawing is on view in this exhibition, along with a reproduction of the original viewing box. Other 18th-century drawings in the exhibition echo the themes of Carmontelle's transparency—landscape, elegant social gatherings, and theatrical performance.

|

|

|

Carmontelle was a master of entertainments at the court of the French ruler Louis-Philippe, duke of Orléans. In addition to creating inventions such as this transparency and its viewing box, he was a playwright, draughtsman, and garden designer.

Carmontelle's audience in the French court surely associated themselves with the fashionable upper classes meandering through this imaginary landscape. The landscape takes viewers on a journey with a new vista at each scene. Couples converse, a pleasure boat makes its way down the river, and an obelisk and pyramid make reference to ancient and far-off lands.

The trees that extend the full height of the composition hide the seams where the sheets of paper are joined together. Carmontelle described how he continuously checked his work by holding the transparent paper against a windowpane to judge how the composition looked when light passed through it.

|

|

|

This drawing by Jacques-André Portail also features an aristocratic outdoor gathering, a favorite theme of 18th-century French artists. The work, which shows two men and two women around an open songbook, is a study for a drawing of a garden party thrown by French minister of culture Philibert d'Orry in 1738.

Like Carmontelle's transparent drawing, this composition shows the staged informality cultivated by the upper classes when engaged in leisure activities.

|

|

|

Besides his transparent drawing, Carmontelle also made more than seven hundred full-length portrait drawings depicting members of the duke of Orléans's court and their visitors.

At the time this work was made, gardening was in vogue among the upper classes, though more as a cultivated interest than a practice. Marie d'Albert de Luynes, the Duchess of Chaulnes, is shown holding a rake as though she were working in this well-tended garden, a performance made even less convincing by her white dress. Contemporary reports indicate that the duchess always wore white, as her husband refused to consummate their marriage. The statue of the goddess Diana in the background is another allusion to her lifelong virginity.

|

|

|

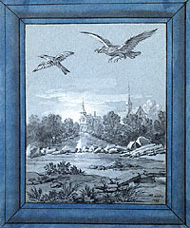

Landscapes and exotic animals were also popular subjects in 18th-century Europe. Between 1729 and 1734 Jean-Baptiste Oudry made more than two hundred drawings featuring animals in landscapes to illustrate the fables of 17th-century French poet Jean de La Fontaine.

In this drawing, two birds fly above a landscape with a small river leading to a house in the distance. This fable uses the eagle's dismissal of the gossiping magpie to demonstrate that discretion is the better part of valor. In 1755 Oudry sold the series to a publisher who used them to illustrate a luxury edition of the fables.

|

|

|

|

Four Figures in Theatrical Costume, Claude Gillot, about 1710

New Acquisition

|

|

|

Theater was another popular interest among upper-class Europeans of Carmontelle's day. Each of the four figures in this drawing represents a variation on stock characters in commedia dell'arte, a form of Italian comedy. Gillot observed the Parisian street performances of these theatrical troupes and was the first French artist to recognize the potential for using its characters and improvised scenes as a subject for art.

The two figures at far left and far right are versions of the pompous doctor character, while the two central figures represent the naive and foppish romantic hero, known as the inamorato ("one in love" in Italian).

The exhibition is located at the Getty Center, Museum, East Pavilion.

|

|