|

|

|

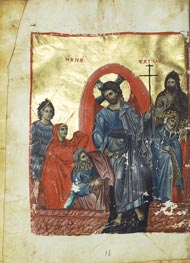

The Descent into Limbo, Nicaea or Nicomedia, late 1200s

|

|

|

|

|

|

Courtly splendor and rich visual arts characterized the Byzantine Empire (330–1453), which inherited the territories and cultural traditions of the eastern Roman Empire. At its height, the Byzantine Empire, whose capital was Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey), reached from Italy to central Asia.

The culture of Byzantium was exported to its neighbors by many means. Byzantine paintings, illuminated books, and silk textiles were brought to the West as diplomatic gifts. Byzantine artistic traditions were also transmitted by traveling artists, scholars, and soldiers. This exhibition explores the influence of Byzantine art on manuscript painting in Germany, Italy, and Armenia.

|

|

|

The Byzantine painting above shows Christ's descent into limbo, which was the primary image for the Easter festival in the medieval Greek Orthodox Church. Christ takes Adam by the wrist and pulls him out of the tomb toward the kingdom of heaven. Abel, Eve, John the Baptist, King Solomon, and King David also wait to be saved. The two kings are dressed in the jeweled crowns and embroidered cloaks of Byzantine emperors.

|

|

|

The art of Byzantium was influenced by the elaborate ceremonies at the emperor's court in Constantinople, the largest and most impressive city in Europe. Illuminated books were painted with gold and bright colors, much like the jewels and precious metals worn by the emperor. Byzantine artists used a set of standard compositions and facial types but also strove to portray the human form in a natural way.

Gospel writers are frequent subjects in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts. Here Saint Mark is shown sharpening his pen, preparing to write the first word of his Gospel. The pose and costume of the saint were derived from portraits of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers. The table, lectern, and writing tools are medieval additions to the scene.

|

|

|

Western European rulers emulated the Byzantine emperor and arranged the marriages of their sons and daughters to Byzantine nobles. German emperor Otto II married Byzantine princess Theophano in 972, sealing an alliance between the German imperial family and the Byzantine aristocracy. Alliances such as this one were accompanied by the exchange of gifts, including illuminated books.

German artists often borrowed themes and styles from Byzantine art. Here a German artist depicts the archangel Gabriel approaching the Virgin, who is dressed in a Byzantine veil. The gold background and the folds and highlights of the angel's drapery reflect aspects of Byzantine art.

|

|

|

The Crusades of the 11th–13th centuries intensified the contact between Byzantium and the West. Western crusaders passed through the Byzantine Empire on their way to Jerusalem, where they hoped to win the Holy Land from Muslim control. Soldiers, merchants, pilgrims, and travelers commissioned works of art from Byzantine artists and from western artists working in the Byzantine style.

The first letter of this Italian manuscript page is decorated with a scene of the nativity. Rather than resting in a stable, as described in the Bible, the Holy Family is sheltered in a cave. The actual site of the Nativity was a grotto in Bethlehem, and the setting in this painting reflects the increased knowledge of the Holy Land through the travels of pilgrims and crusaders.

|

|

|

Armenia was an independent Christian state at the eastern edge of the Byzantine Empire. The Armenian Church was separate from the Byzantine Orthodox Church, but it drew heavily from early Byzantine religious art. Armenian artists developed a distinct style that drew from many sources, including Byzantium, Islam, and the West.

The decorative motifs on this Armenian canon table page are similar to those found in Byzantine books. The numbers, which represent passages in the Gospels, are set in a fantastic architectural frame complete with capitals painted as female heads. The naturalistic birds and trees contrast with the brightly colored geometric patterns.

|

|

|

The Byzantine Empire ended in 1453 with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. Western rulers continued to admire the fallen Byzantine Empire, however, and the artistic traditions of Byzantium continued to influence western artists. Artists painted imaginary Byzantine scenes that were often far removed from historical reality.

This leaf depicts Frankish king Charles Martel and his vassal Gerard de Roussillon being welcomed into Constantinople by the Byzantine emperor. This event took place in the 700s, but the artist depicted the Byzantine emperor in the ermine-lined cloak and crown common to western kings in the 1400s.

The exhibition is located at the Getty Center, Museum, North Pavilion.

|

|