|

The architectural wonders of soaring cathedrals and majestic castles are some of the greatest achievements of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. While many of these spectacular buildings no longer survive, vivid records can be found in manuscript illumination. This exhibition explores how medieval artists incorporated architecture into scenes from scripture, literature, and history, manipulated the forms of buildings to convey symbolic meaning, and used architectural elements as decorative motifs to fill the landscape of the painted page.

The Old Testament figure Nimrod, king of Babylonia, oversees the construction of a tower. Details suggest medieval working methods, such as the planks of a wooden scaffold which support several men who receive stones hauled upward by a pulley system.

|

|

|

Medieval buildings often seem far removed from our own modern architecture, but they are sometimes direct ancestors of structures we build today. Beyond the castles and cathedrals that spark our imagination, manuscripts often present the landscapes of the time filled with a variety of other domestic and sacred structures.

The artist sets this story in a prosperous medieval Flemish city of the fifteenth century, offering an evocative view of its tall, stately houses and paved streets. Painted entirely in soft shades of gray, a technique known as grisaille, the scene features buildings and figures notable for their precision and sculptural qualities.

|

|

|

Illuminated manuscripts often served as historical documents of medieval architecture. The dedication or renovation of a church, an important event, was often represented in books created to celebrate the occasion. Manuscripts sometimes depicted buildings associated with a book's owner, making a kind of visual inventory of architectural possessions.

The foundation of a new church was one of the most common types of building recorded in medieval texts and images. This scene commemorates the patron's dedication of a new convent at Trebnitz. Saint Hedwig is shown in blue, directing the building project where workers apply mortar and lay down bricks. Notice the tall lancet windows, which are common features of Gothic churches.

|

|

|

Many of the manuscripts that survive from the Middle Ages contain texts drawn from the Old and New Testaments of the Christian Bible. Architecture is a frequent setting for biblical stories, and in some cases buildings themselves play key roles in the narratives. Illustrations of these texts provide intriguing insights into the medieval perception of architecture.

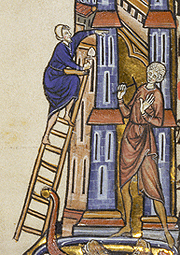

Here, the letter I is embellished by the artist to contain a scene of the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, which had been destroyed by the Babylonians. The ancient historical event is depicted in contemporary terms; the workmen are represented as medieval masons. A craftsman perched on a ladder wields a small trowel for applying mortar, while his partner to the right holds a pick.

|

|

|

Medieval artists depicted architecture not only to record the world around them, but also to convey meaning. Architecture was often used to suggest the importance or holiness of a figure or event. Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints, as well as secular individuals, were frequently framed by structural elements such as the arch or the niche.

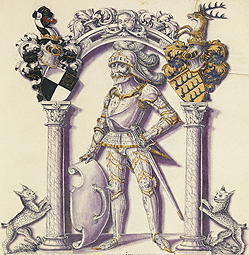

In this portrait of Fritz Hohenzollern in elaborate armor, the artist poses the aristocrat under a large rounded arch that is reminiscent of Roman triumphal arches. This adds to his grandeur and emphasizes his authority and wealth.

|

|

|

Columns, arches, niches, and tracery often appear in the borders of illuminated pages, enshrining text and image within the decorative forms of medieval and Renaissance architecture. These bits of buildings do not make sense as stand-alone structures. Instead, they were used for their aesthetic value and to suggest the grand edifices or sacred spaces they adorned.

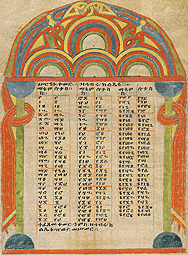

In this canon table from Ethiopia, colorful architectural forms embellish a Gospel book index. The framework is alive with bold decorative details, including concentric half-circles drawn with a compass. Abstract knot-work patterns fill the archway, recalling Celtic interlace motifs. The curtains wound around the columns reflect the textiles used to partition church spaces.

|

|